The Hwaseong of Mashville (매쉬빌), a far out rural backwater, is a kind frontier town drenched in moonshine and melancholy where the local pastime is loneliness. You can almost see what attracted the murderous cultists at the film’s centre to their strange conviction that a convoluted ritual will save a world that’s fallen into chaos with “pure love”, were it not that one of them also remarks on how foolish he feels remembering himself as man who once believed all were equal before the law.

The law in these parts is a laughing policeman who doesn’t like it when things happen outside of his jurisdiction, but actually does not very much at all to prosecute the “pseudo-religion” he later tells a colleague he’s been tracking while arriving to clear up their mess. Otherwise, there are two other concurrent crimes that should probably be pressing on his time including the deadly moonshine pedalled by liquor entrepreneur Se-jeong and his two bearded brothers, and the strange case of a young woman charged with acquiring a fake zombie corpse for a movie shoot only to turn up with what she suspects is an actual dead body. A rather strange set of events brings them all into the same orbit while preventing them from leaving Hwaseong where the cultists, who are all male but dress in female hanbok for otherwise unexplained reasons, are still on the prowl looking to complete their zodiac of sacrificial victims.

Then again, the cultists may be victims too. Their former leader soon turns up in town apparently regretting his life’s work while explaining cryptically that the darkness is in his bag, which turns out to be full of money. We sees the eyes flash of Hyun-man, a local man, when he opens it as if he were corrupted in one instant though this day of being targeted by religious extremists already seems to have taken its toll on him. In the opening sequence, he’d celebrated a kind of birthday with two friends, asking only for a hug but both men refused him. He’s also one of the few villagers that didn’t leave on a trip to the hot springs which lends Hwaseong a lonelier air than it might otherwise have had.

Even the brothers are longing for someone, yearning for the return of their mother who abandoned them many years ago and if Se-jeong’s dream is to be believed sending them the incredibly inappropriate gift of Wild Turkey whiskey when they were just kids waiting for her to come home. Se-jeong feels he can’t leave Hwaseong because a part of him’s waiting for his mother to come back, but the other half is perhaps just afraid to do so. In any case, a mistake by his strange brothers seems to have turned his whiskey into poison, so his hand’s been forced even if it weren’t for all the other weird goings on.

The irony maybe that pure love really does save the world, Se-jeong reflecting that he might have been in love for the first time in his life while finally gaining the courage to move on from Hwaseong in acceptance of the fact his mother likely won’t be returning anyway. His brothers almost got inducted into the cult, mistaken as fellow priests and strangely captivated by the weird ritual movements the killers perform of over the bodies acknowledging that there is something relaxing in thrusting their hands up into the air while curious enough about the ritual to see it through despite its grimness and moral indefensibility.

Like the cult’s beliefs, not much makes a lot of sense though Hwang lends his strange small town enough crazy vibes to make it all hang together in a place in which whiskey itself appears to be close to a religion and as much of a salve for the world’s unkindness as anything else. “You need to quit drinking,” one his brothers ironically tells Se-jeong when he tries tell him about his recent emotional experiences though in another way he may actually have been saved by an unexpected miracle provoked by the ritual which didn’t work in the way it was intended but may have banished darkness from Se-jeong’s life at least, freeing him from a life in “mash ville” and the kind of the liquor that causes the dead to rise.

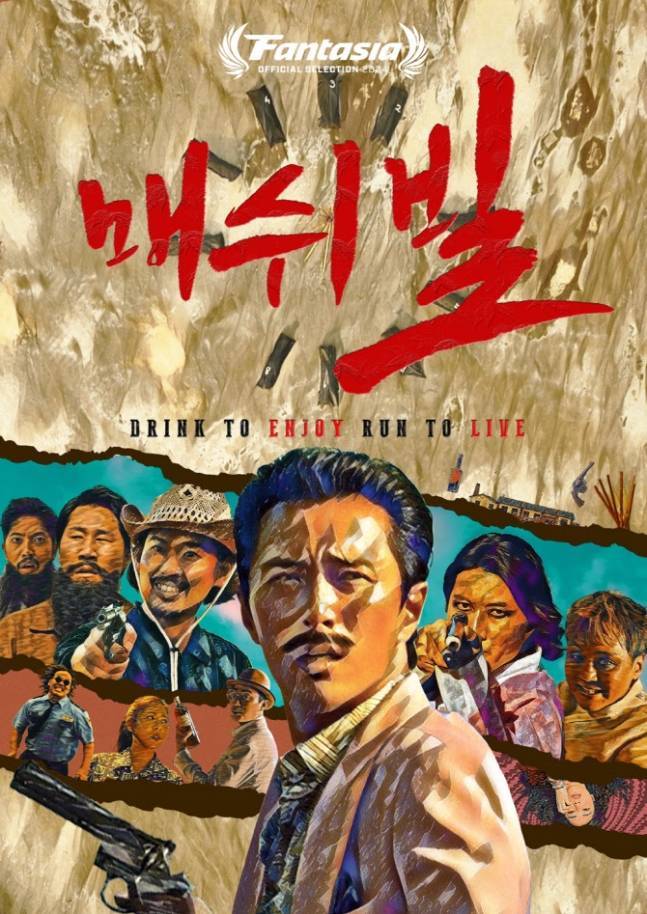

Mash Ville screened as part of this year’s Fantasia International Film Festival.

Trailer (English subtitles)