Following last year’s inaugural online edition, the Taiwan Film Festival Edinburgh returns for 2021 in a hybrid format featuring a few in-person screenings as well as an extensive online programme running entirely for free in the UK from 25th to 31st October.

IN-PERSON SCREENINGS in Glasgow and Edinburgh

Sacred Forest 神殿| Ke Chin-Yuan| 2019 | 60 mins

In-person screening on 25 October at Glasgow Film Theatre; tickets on sale soon.

Ecological documentary exploring Taiwan’s unique ecosystem from the point of view of six different groups each with different interests and specialities as they explore the majesty of the forest.

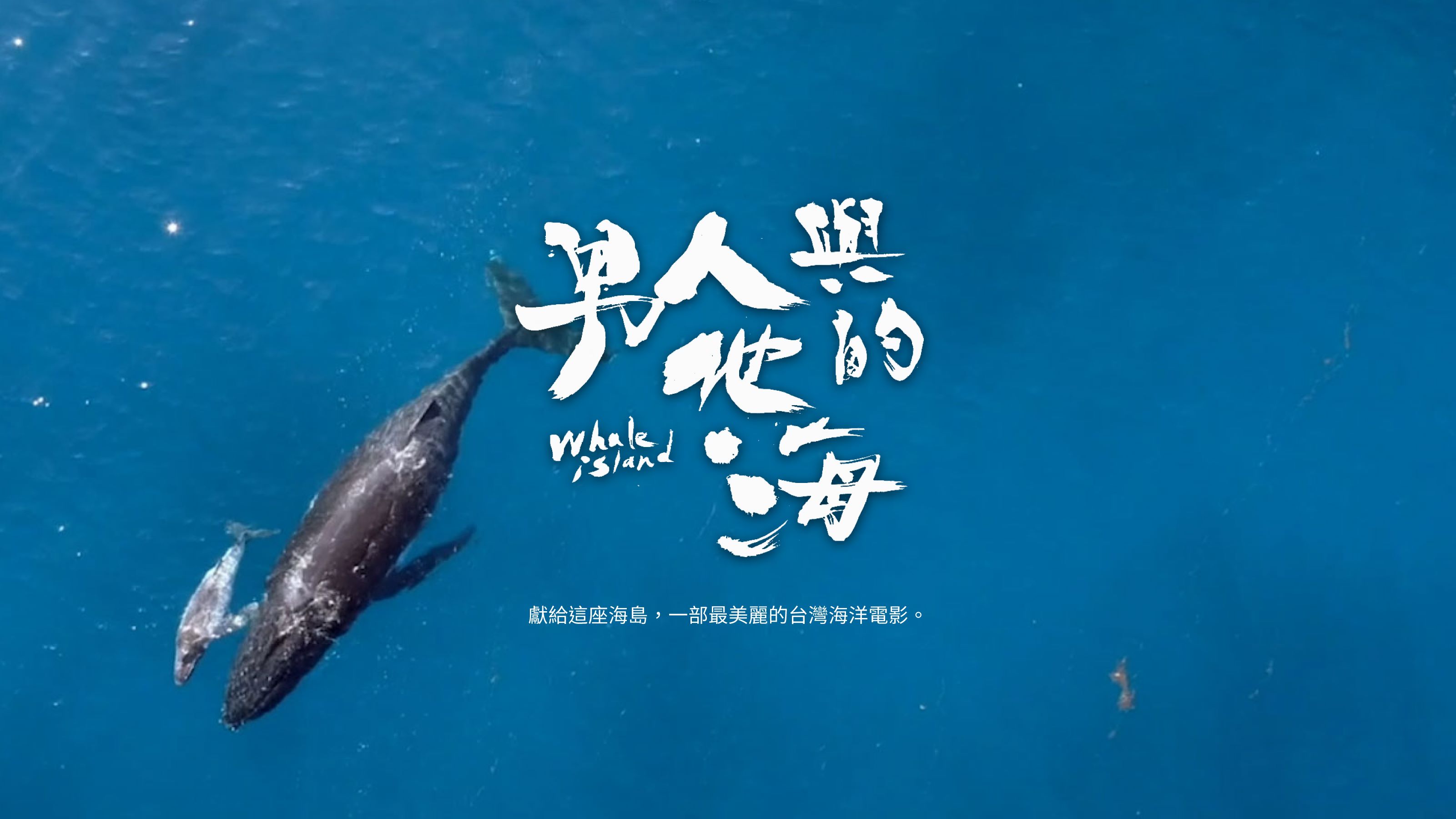

Whale Island 男人與他的海 | Huang Chia-Chun| 2020 | 108 mins | UK Premiere

In-person screening on 30 October at Glasgow Film Theatre; tickets on sale soon.

Capturing the power and mystery of the sea, Huang’s beautifully shot nature doc contemplates Taiwan’s relationship with the oceans which surround it. Review.

Sounds in Silence double bill at 6.30pm on 27 October in Summerhall, Edinburgh; also online 28-31 Oct on Festival website.

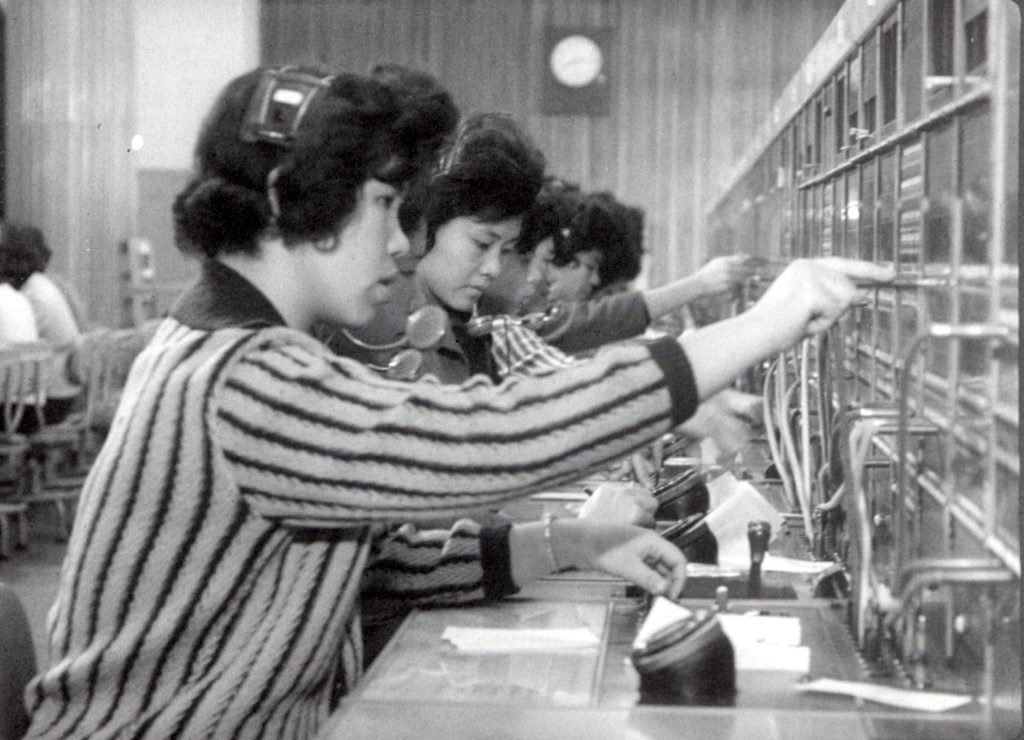

A Morning in Taipei 臺北之晨 | Pai Jing-jui | 1964 | 20 mins | UK Premiere

1964 documentary short capturing a newly industrious Taipei in which a variety of individuals go about their regular morning routines.

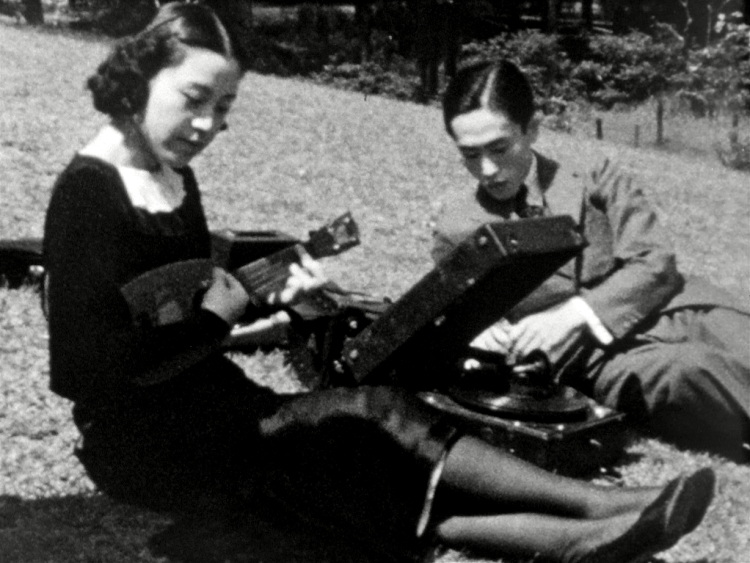

Deng Nan-guang’s 8mm Movies 鄧南光8mm家庭電影| Deng Nan-guang| 1935-1941| 57 mins| UK Premiere

A collection of home video-style recordings captured between 1935 and 1941 and bearing witness to an overlooked era of Japanese occupation in the shadow of the second world war.

DIGITAL SCREENINGS on the Festival website between 25 and 31 October

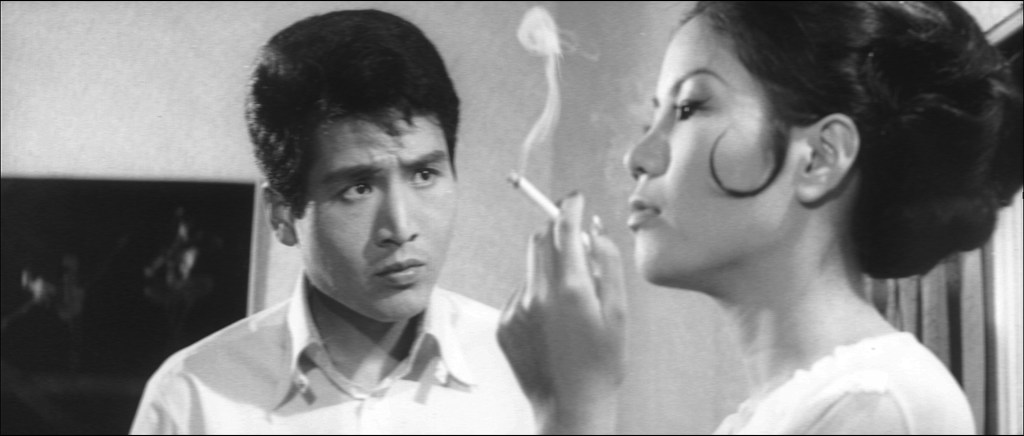

The Best Secret Agent 天字第一號 | Chang Ying | 1964 | 102 mins

Taiwanese-language remake of a popular film from 1945 in which a young woman flees the Japanese occupation with her father and falls in love with a kind and idealistic young man. When her father is killed in an airstrike, she realises she must give up on romance in order to avenge his death by becoming a master spy!

Foolish Bride, Naive Bridegroom 三八新娘憨子婿| Hsin Chi | 1967 | 101 mins

A naive young couple’s desire to marry is frustrated by the revelation their parents were once lovers in Hsin’s delightful screwball rom-com. Review.

Dangerous Youth 危險的青春 | Hsin Chi | 1969 | 95 mins

A recently dumped delivery driver becomes fond of a waitress and tries to get her another job after meeting a guy who runs a cabaret bar but the job turns out to be as an escort to an elderly millionaire.

The Homecoming Pilgrimage of Dajia Mazu 大甲媽祖回娘家| Huang Chun-ming | 1975 | 27 mins | UK Premiere

Documentary capture of the annual Taoist celebration of the Dajia Mazu Pilgrimage from 1974. This recently restored edition features the original language track in Taiwanese Hokkien once banned under the KMT’s Mandarin-only policy.

Taipei Story 青梅竹馬 | Edward Yang | 1985 | 115 mins

Edward Yang’s landmark 1985 drama in which an independent, financially secure woman is determined to move forward while her boyfriend (played by film director Hou Hsiao-Hsien) remains trapped in the past.

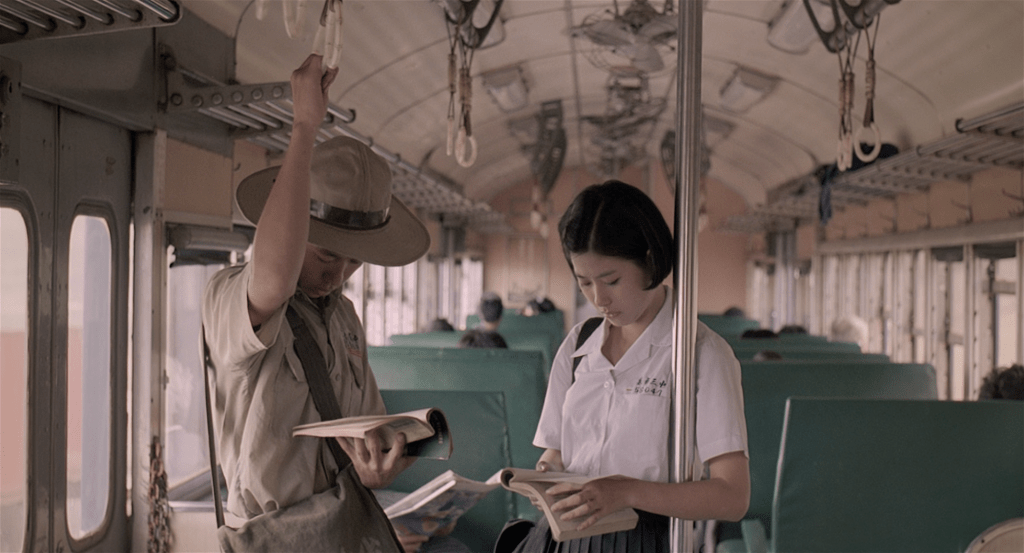

Dust in the Wind 戀戀風塵 | Hou Hsiao-Hsien | 1986 | 109 mins

A young couple from a rural village travel to Taipei hoping to make enough money to marry, but their dreams of romance are crushed when the boy is drafted into the Republic of China Army.

Peony Birds 牡丹鳥 | Huang Yu-shan| 1990 | 107 mins | UK Premiere

Melodrama exploring the troubled relationship of a mother and daughter bound by mutual resentment. A Q&A session with director Huang Yu-shan will also be available via the streaming platform.

Hill of no Return 無言的山丘 | Wang Tung | 1992 | 175 mins

Two brothers leave home after the deaths of their parents to work at a Japanese-run goldmine in 1927 but rather than the riches they dreamed of find only exploitation and disappointment. A Q&A session with director Wang Tung will also be available via the streaming platform.

The Personals 徵婚啓事 | Chen Kuo-Fu | 1998 | 105 mins

A heartbroken eye doctor quits her job at a hospital and plans to get married, placing a personal ad to find the perfect partner in this humorous exploration of the ’90s Taipei dating scene.

Splendid Float 豔光四射歌舞團 | Zero Chou | 2004 | 73 mins

A Taoist priest with a sideline as a drag artist falls for someone who later disappears without saying goodbye leaving him wondering if something terrible may have occurred.

Closing Time 打烊時刻 | Nicole Vogele | 2018 | 116 mins

Documentary from Swiss filmmaker Nicole Vogele following the city’s nighttime economy from the vantage point of an ageing couple’s late night eatery.

Taiwan Film Festival Edinburgh takes place online and in-person 25th to 31st October, 2021. All films stream for free in the UK via the official platform though ticket numbers are limited and early booking is advised. Full details are available via the official website and you can also keep up with all the latest details by following the festival on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and YouTube.