1973 is the year the ninkyo eiga died. Or that is to say, staggered off into an alleyway clutching its stomach and vowing revenge whilst simultaneously seeking forgiveness from its beloved oyabun after being cruelly betrayed by the changing times! You might think it was Kinji Fukasaku who turned traitor and hammered the final nail into the coffin of Toei’s most popular genre, but Sadao Nakajima helped ram it home with the riotous explosion of proto-punk youth movie and jitsuroku-style naturalistic look at the pettiness and squalor inherent in the yakuza life – Aesthetics of a Bullet (鉄砲玉の美学, Teppodama no Bigaku). This tale of a small time loser playing the supercool big shot with no clue that he’s a sacrificial pawn in a much larger power struggle is one that has universal resonance despite the unpleasantness of its “hero”.

1973 is the year the ninkyo eiga died. Or that is to say, staggered off into an alleyway clutching its stomach and vowing revenge whilst simultaneously seeking forgiveness from its beloved oyabun after being cruelly betrayed by the changing times! You might think it was Kinji Fukasaku who turned traitor and hammered the final nail into the coffin of Toei’s most popular genre, but Sadao Nakajima helped ram it home with the riotous explosion of proto-punk youth movie and jitsuroku-style naturalistic look at the pettiness and squalor inherent in the yakuza life – Aesthetics of a Bullet (鉄砲玉の美学, Teppodama no Bigaku). This tale of a small time loser playing the supercool big shot with no clue that he’s a sacrificial pawn in a much larger power struggle is one that has universal resonance despite the unpleasantness of its “hero”.

Kiyoshi Koike is a former chef with a gambling problem and a living room full of rabbits that he bought hoping to sell as pets but his sales patter could use some work and the business is not exactly taking off. Getting violent with his girlfriend after borrowing money from her to play mahjong and then getting annoyed when she doesn’t seem keen to lend him more to change his rabbit business into a dog business, Kiyoshi is at an impasse. So, when the local gangsters are looking for a patsy they can send into enemy territory as a “bullet” Kiyoshi’s name is high on the list. They need someone “hotblooded, must have daredevil courage, when he flips he should make a huge racket” – Kiyoshi more than fits the bill, and more to the point he has no idea what he’s doing.

Given a large amount of money and a gun, Kiyoshi gets a haircut and buys some fancy suits to play his part as a super cool gangster who doesn’t take any shit from anyone. He goes around telling everyone his name and gang affiliation very loudly, waving his pistol and acting like a big shot despite the fact he obviously has no name and no reputation. The plan is he fires his gun, gets killed, his gang swoop in for a gang war and wipe out the opposition. Only, when Kiyoshi gets too invested in his part and beats up a rival gangster, the local boss apologises and offers him a knife to make things even with the guy who just disrespected him…

If he fires his gun, it’s game over but what exactly is keeping his finger off the trigger – fear, or self preservation? Either way, Kiyoshi is way over his head in a game he never understood in the first place.

This is no ninkyo eiga. There’s no nobility here, these men are animals with no humanity let alone a pretence of honour. Kiyoshi is a loser, through and through, but once the gun is in his hand he transforms into something else. The gun becomes an extension of himself, a symbol of his new found gangster hero status. A fancy suit and a fire arm are handy props for a method actor but the performance only runs so deep, what is Kiyoshi now, a man, or a bullet?

Whatever he is, he’s no hero. In his untransformed state he violently beat his girlfriend whom he also forced to work as a prostitute, and even after getting the gun he witnesses a woman being gang raped yet appears to be more amused than anything else. He ends up getting into a fight with the other two guys waiting for their go and seems to feel heroic after the woman gets away but his intention was never to rescue her. Indeed, bumping into her again he makes a clumsy attempt at subtle blackmail though she gets a kind of revenge on him in the end. Even his “romantic” encounter with the glamorous former photo model girlfriend of the rival gang boss ends with a bizarre sex game in which he makes her get on all fours and bark like a dog.

When the time comes, Kiyoshi can’t contemplate the idea of returning to his old loser self and is fixated on reaching the peak of Kirishima which is said to be the place where the gods descended to Earth. When the bullet finally emerges, it heads in the wrong direction. Self inflicted wounds are the name of the game as an aesthetically pleasing, poetic end to this tragic story follows the only trajectory available for a classic yakuza fable.

After beginning with a montage of people sloppily eating junk food set against a proto-punk rock song dedicated to the idea of living the way you please and not letting anyone get in your way, the film contrasts the independent, non-conformist yakuza ideal of total freedom with Kiyoshi’s lowly status in an increasingly consumerist environment. The yakuza life would indeed prove a passport for a man like Kiyoshi to jump into the mainstream, but this fantasy world is one that cannot last and one way or another the curtain must fall on this expensive piece of advanced performance art.

Aesthetics of a Bullet has, like its hero, been abandoned on the roadside. Whereas the Battles Without Honour series has become a landmark of the yakuza genre, Aesthetics of a Bullet has never even received a home video release in Japan and has received barely a mention even the histories of ATG movies. This is surprising as its noir style and art house approach ought to have made it one of ATG’s more commercially viable releases even with its sleazy, nihilistic tone. Opting for a more naturalistic approach, Nakajima nevertheless breaks the action with expressionistic sequences as Kiyoshi fantasises a glorious death for himself, climaxes through gunshot, or remembers the student riots through a blue tinted sequence of still photographs. A complex yet beautifully made, genre infused character piece, Aesthetics of a Bullet is a long lost classic and one in urgent need of reappraisal.

Title sequence and first scene (unsubtitled)

Yusuke Iseya is a rather unusual presence in the Japanese movie scene. After studying filmmaking in New York and finishing a Master’s in Fine Arts in Tokyo, he first worked as model before breaking into the acting world with several high profile roles for internationally renowned auteur Hirokazu Koreeda. Since then he’s gone on to work with many of Japan’s most prominent directors before making his own directorial debut with 2002’s Kakuto. Fish on Land (セイジ -陸の魚-, Seiji – Riku no Sakana), his second feature, is a more wistful effort which belongs to the cinema of memory as an older man looks back on a youthful summer which he claimed to have forgotten yet obviously left quite a deep mark on his still adolescent soul.

Yusuke Iseya is a rather unusual presence in the Japanese movie scene. After studying filmmaking in New York and finishing a Master’s in Fine Arts in Tokyo, he first worked as model before breaking into the acting world with several high profile roles for internationally renowned auteur Hirokazu Koreeda. Since then he’s gone on to work with many of Japan’s most prominent directors before making his own directorial debut with 2002’s Kakuto. Fish on Land (セイジ -陸の魚-, Seiji – Riku no Sakana), his second feature, is a more wistful effort which belongs to the cinema of memory as an older man looks back on a youthful summer which he claimed to have forgotten yet obviously left quite a deep mark on his still adolescent soul. Being stood up is a painful experience at the best of times, but when you’ve been in prison for three whole years and no one comes to meet you, it is more than usually upsetting. Sixth generation Oyabun of the Ona clan, Daisaku, has made a new friend whilst inside – Taro is a younger man, slightly geeky and obsessed with bombs. Actually, he’s a bit wimpy and was in for public urination (he also threw a firecracker at the policeman who took issue with his call of nature) but will do as a henchman in a pinch. Daisaku wanted him to see all of his yakuza guys showering him with praise but only his son actually turns up and even that might have been an accident.

Being stood up is a painful experience at the best of times, but when you’ve been in prison for three whole years and no one comes to meet you, it is more than usually upsetting. Sixth generation Oyabun of the Ona clan, Daisaku, has made a new friend whilst inside – Taro is a younger man, slightly geeky and obsessed with bombs. Actually, he’s a bit wimpy and was in for public urination (he also threw a firecracker at the policeman who took issue with his call of nature) but will do as a henchman in a pinch. Daisaku wanted him to see all of his yakuza guys showering him with praise but only his son actually turns up and even that might have been an accident. The somewhat salaciously titled Black Kiss (ブラックキス) comes appropriately steeped in giallo-esque nastiness but its ambitions lean towards the classic Hollywood crime thriller as much as they do to gothic European horror. Directed by the son of the legendary father of manga Osamu Tezuka (not immune to a little strange violence of his own) Macoto Tezuka, Black Kiss is a noir inspired tale of Tokyo after dark where a series of bizarre staged murders are continuing to puzzle the police.

The somewhat salaciously titled Black Kiss (ブラックキス) comes appropriately steeped in giallo-esque nastiness but its ambitions lean towards the classic Hollywood crime thriller as much as they do to gothic European horror. Directed by the son of the legendary father of manga Osamu Tezuka (not immune to a little strange violence of his own) Macoto Tezuka, Black Kiss is a noir inspired tale of Tokyo after dark where a series of bizarre staged murders are continuing to puzzle the police. Poor old Hyuk-jin is about to have the worst “holiday” of his life in Noh Young-seok’s ultra low budget debut, Daytime Drinking (낮술, Natsul). Currently heartbroken and lovesick as his girlfriend has just broken up with him, Hyuk-jin is trying to cheer himself up with an evening out drinking with old university friends. Truth be told, they aren’t terribly sympathetic to his pain though one of them suddenly suggests they all take a trip together just like they did when they were students. Hyuk-jin plays the party pooper by saying he can’t go because he’s meant to be looking after the family dog but after some gentle ribbing he relents and says he’ll come if he can get someone to look in on the puppy for him while he’s gone. He will regret this.

Poor old Hyuk-jin is about to have the worst “holiday” of his life in Noh Young-seok’s ultra low budget debut, Daytime Drinking (낮술, Natsul). Currently heartbroken and lovesick as his girlfriend has just broken up with him, Hyuk-jin is trying to cheer himself up with an evening out drinking with old university friends. Truth be told, they aren’t terribly sympathetic to his pain though one of them suddenly suggests they all take a trip together just like they did when they were students. Hyuk-jin plays the party pooper by saying he can’t go because he’s meant to be looking after the family dog but after some gentle ribbing he relents and says he’ll come if he can get someone to look in on the puppy for him while he’s gone. He will regret this.

Hiroshi Shimizu is well known as one of the best directors of children in the history of Japanese cinema, equalled only by the contemporary director Hirokazu Koreeda. The Shiinomi School (しいのみ学園, Shiinomi Gakuen) is one of the primary examples of his genius as it takes on the controversial themes of the place of the disabled in society and especially how children and their parents can come to terms with the many difficulties they now face.

Hiroshi Shimizu is well known as one of the best directors of children in the history of Japanese cinema, equalled only by the contemporary director Hirokazu Koreeda. The Shiinomi School (しいのみ学園, Shiinomi Gakuen) is one of the primary examples of his genius as it takes on the controversial themes of the place of the disabled in society and especially how children and their parents can come to terms with the many difficulties they now face. No names, no strings. That’s the idea at the centre of Daisuke Miura’s adaptation of his own stage play, Love’s Whirlpool (愛の渦, Koi no Uzu). Love is an odd word here as it’s the one thing that isn’t allowed to exist in this purpose built safe space where like minded people can come together to experience the one thing they all crave – anonymous sex. From midnight to 5am this group of four guys and four girls have total freedom to indulge themselves with total discretion guaranteed.

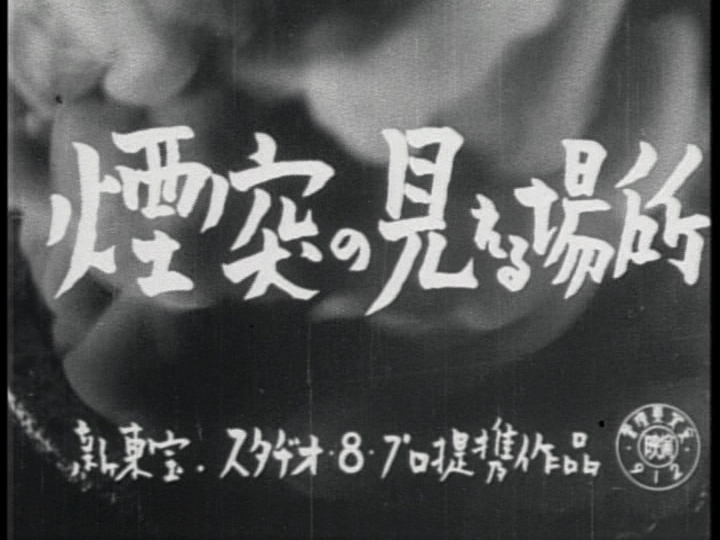

No names, no strings. That’s the idea at the centre of Daisuke Miura’s adaptation of his own stage play, Love’s Whirlpool (愛の渦, Koi no Uzu). Love is an odd word here as it’s the one thing that isn’t allowed to exist in this purpose built safe space where like minded people can come together to experience the one thing they all crave – anonymous sex. From midnight to 5am this group of four guys and four girls have total freedom to indulge themselves with total discretion guaranteed. Where Chimneys are Seen (煙突の見える場所, Entotsu no Mieru Basho) is widely regarded as on of the most important films of the immediate post-war era, yet it remains little seen outside of Japan and very little of the work of its director, Heinosuke Gosho, has ever been released in English speaking territories. Like much of Gosho’s filmography, Where Chimneys are Seen devotes itself to exploring the everyday lives of ordinary people, in this case a married couple and their two upstairs lodgers each trying to survive in precarious economic circumstances whilst also coming to terms with the traumatic recent past.

Where Chimneys are Seen (煙突の見える場所, Entotsu no Mieru Basho) is widely regarded as on of the most important films of the immediate post-war era, yet it remains little seen outside of Japan and very little of the work of its director, Heinosuke Gosho, has ever been released in English speaking territories. Like much of Gosho’s filmography, Where Chimneys are Seen devotes itself to exploring the everyday lives of ordinary people, in this case a married couple and their two upstairs lodgers each trying to survive in precarious economic circumstances whilst also coming to terms with the traumatic recent past. Making a coming of age film when you’re only 14 is, in many ways, quite a strange idea but this debut feature from Ryugo Nakamura was indeed directed by a 14 year old boy. Focussing on a protagonist not much younger than himself and set in his native Okinawa, Catcher on the Shore (やぎの冒険, Yagi no Boken) is the familiar tale of a city boy at odds with his rural roots and the somewhat cosy, romantic relationship people from the town often have with matters of the countryside.

Making a coming of age film when you’re only 14 is, in many ways, quite a strange idea but this debut feature from Ryugo Nakamura was indeed directed by a 14 year old boy. Focussing on a protagonist not much younger than himself and set in his native Okinawa, Catcher on the Shore (やぎの冒険, Yagi no Boken) is the familiar tale of a city boy at odds with his rural roots and the somewhat cosy, romantic relationship people from the town often have with matters of the countryside.