Named after Japan’s oldest brand of cigarettes, Golden Bat is regarded by some as the nation’s first superhero created as a character for Kamishibai in 1931 by Takeo Nagamatsu and Suzuki Ichiro. Drawing inspiration from mythological illustrations, Nagamatsu and Ichiro had however intended Golden Bat to be rooted in science rather than legend which might seem ironic on viewing Hajime Sato’s 1966 piece of Toei tokusatsu titled simply The Golden Bat (黄金バット, Ogon Bat).

Though Toho might be more closely associated with big screen tokusatsu adventures, Toei also had a small sideline in special effects movies as well as a series of hugely popular television franchises. Back in the 1960s, however, Golden Bat was something of an outlier in that it shifts away from the predominant messages that underlined many post-war tokusatsu in the importance of responsible science favouring instead a kind of throwback to the 1930s serial origins of the title character. As the film opens a factory worker with an obsessive though amateur interest in astronomy, Kazahaya (Wataru Yamakawa), tries to convince a professor that the planet Icarus has left its regular orbit and is on an imminent collision course with the Earth. The professor, however dismisses him, stating that his story might appeal to the tabloids but “it is essential that scientists examine any situation carefully” (which he doesn’t seem interested in doing). An assistant then arrives to back him up, adding that as they live in a world in which mankind has been to the moon “the universe no longer poses any terror for us” which sounds like quite an irresponsible statement for a scientist to make.

In any case, according to Kazahaya Icarus is going to collide with the Earth in under 10 days so there isn’t much time for careful investigation anyway. On his way out of the building he’s accosted by two scary looking guys, but contrary to expectation they aren’t from some shady government organisation carting him off because he knows too much but from the super secretive Pearl Research Institute which has apparently been following him closely and wants to offer him a job because he’s right about Icarus. In another break with the usual tokusatsu anti-nuclear messages, Pearl has developed the “Hyper Annihilator Beam Cannon” which, using a special lens they haven’t developed yet, can turn a ray of atomic light into a heat beam with the power of a thousand H-bombs. They plan use this to blow up Icarus before it hits the Earth (no mention is ever made about whether or not Icarus is also inhabited). It’s about this time that their expeditionary force begins sending distress signals and then drops out of contact, the gang then discovering Icarus is part of a master plan operated by the evil inter galactic villain Nazo who thinks that only he deserves to exist so wants the Earth destroyed.

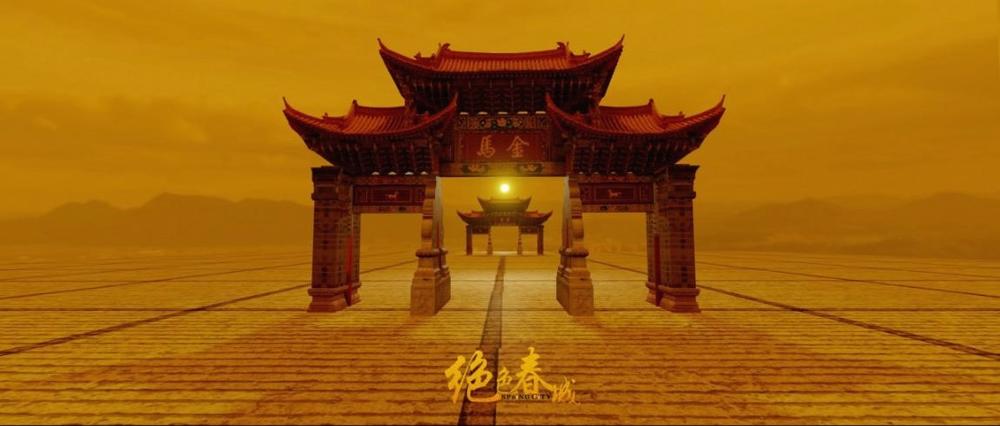

Nazo is Golden Bat’s arch enemy, here a man in a rat costume with four eyes and a large metal wrench for a hand. Travelling to find their fallen comrades, the gang discover Golden Bat in his sarcophagus hidden in what looks like an ancient temple with instructions to wake him up with a single drop of water should humanity be in crisis which he predicts will happen 10,000 years after he went into storage in Atlantis. Professor Pearl’s adorable 12-year-old granddaughter Emily (Emily Hatoyama) does just this and then becomes his point of contact, but in true tokusatsu fashion after simply gifting them the special lens and fighting off Nazo’s goons Golden Bat flies off into the sunset with important superhero business to attend to. Meanwhile, Captain Yamatone (Sonny Chiba) and the others attempt to save the Earth while battling Nazo’s three most dangerous henchmen: wolfman Jackal (Keiichi Kitagawa), fish woman Piranha (Keiko Kuni), and Keloid (Yoichi Numata) who has a large skin lesion on his face which honestly seems in poor taste.

As in his other films, Sato appears to have his tongue very much in his cheek given that the performances of his cast are decidedly broad with a tendency towards evil glares and reaction shots, his camera often zooming in directly on villainy. Golden Bat meanwhile is often seen striking theatrical poses while uttering phrases such as “for justice alone do I fight!” and hitting people with his baton to make them behave. You might think children would find a skeleton man with an eyeless gold skull a little frightening, but Golden Bat seems to make it work while offering his own non-evil laugh as he cheerfully returns to save the day until finally forced to tap the sign he’s helpfully put up reading “those who attempt to subjugate the world through force by their own force shall perish”. Nazo meanwhile has a definite nautical theme, travelling by shark submarine/aeroplane and giant squid-shaped earth borer with laser eyes but is finally undone in surprisingly violent fashion by Golden Bat’s Baton of Justice. Defiantly irreverent and flying in the face of tokusatsu’s general responsible science stance, Golden Bat is exceptionally silly and makes little literal sense but is undeniably fantastic fun as the skeletal superhero does his best to ward off galactic imperialism.

Original trailer (no subtitles)