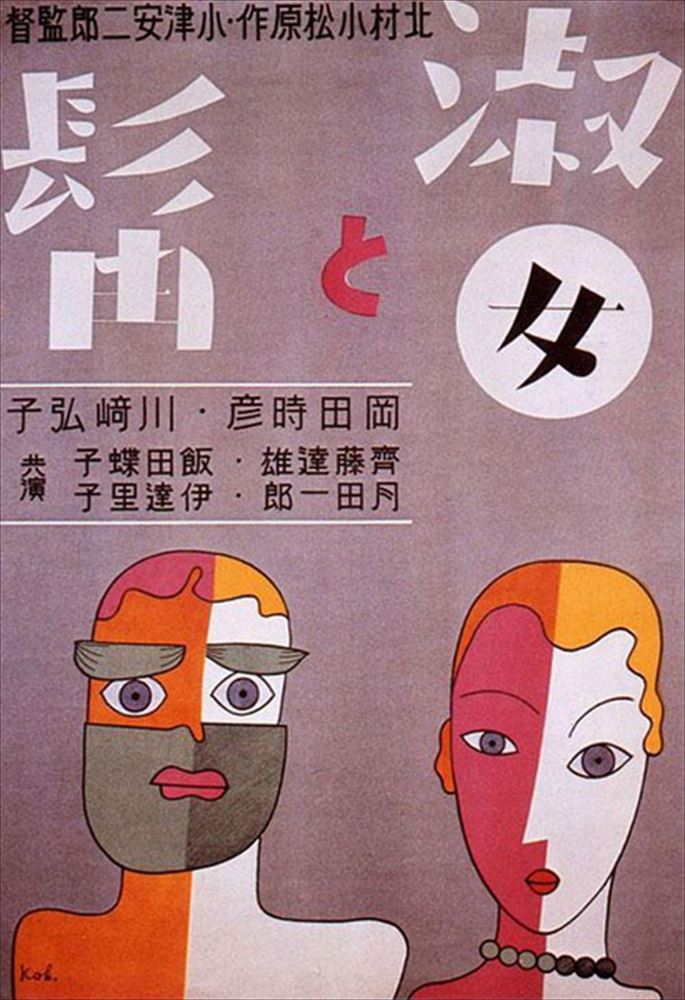

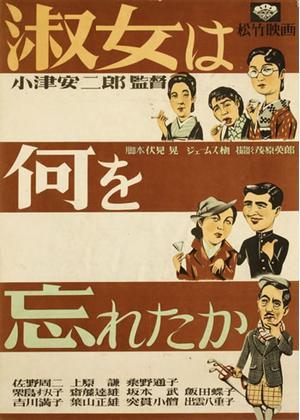

Yasujiro Ozu has sometimes been dismissed as middle of the road, particularly by the young radicals of the post-war generation who saw his, by then, rather conservative films as a symbol of everything they sought to reject in their national cinema. They may in some senses have had a point and, in 1931’s The Lady and the Beard (淑女と髭, Shukujo to hige), Ozu does indeed show us that the middle of the road might be the best place to be as his basically good yet rigidly traditionalist hero is cajoled towards modernity but ultimately rejects its extremes in pulling a “modern girl” back towards the path of righteousness.

Recent graduate Okajima (Tokihiko Okada) is a kendo enthusiast with a rather unsettling beard which he has long refused to shave. Other than his strangely close friendship with nobleman Teruo (Ichiro Tsukida), he appears to have been rejected by mainstream society because of his odd appearance and socially awkward behaviour. Teruo invites him to his sister’s birthday party without bothering to ask her and consequently scandalises all of her friends who vow to humiliate Okajima as soon as he arrives. Okajima, however, has no idea he is being made fun of. He declines the invitation to dance with the young women in the modern fashion but volunteers to do a dance on his own, prancing about with a fan and waving his sword around in an unexpected display of traditional performance. When Teruo and his sister return after having a private argument, the party is ruined. All the girls have left, for reasons which Okajima seems not to understand.

He is at least, however, chivalrous. Spotting a young woman in kimono being mugged in the street by a modern girl, he wades in to help, earning her eternal admiration while fending off the other members of the modern girl’s gang with his kendo skills. His heroism further pays off when he discovers that the woman he saved, Hiroko (Hiroko Kawasaki), is a typist at an office where he is interviewing for a job. Hiroko is able to explain to him that the reason he was turned down, despite the fact that the boss also had a big bushy beard, was his facial hair so he should try shaving it off.

The beard is a symbol not only of Okajima’s traditional mindset but of a certain kind of masculinity which might not be welcome in the modern world. Teruo tries to defend it to his sister by showing her portraits of various great men from the past who all had facial hair while Okajima claims that his is inspired by Abraham Lincoln and is intended to put women off so that he doesn’t get distracted from becoming a great man himself. Okajima’s robust masculinity, avoidance of women, and intense friendship with Teruo, anxious should he get the wrong idea about women in his apartment, might hint at another possibility, but that soon goes out the window when he sheds the beard and instantly becomes irresistible to women. Not only is he developing a romantic relationship with the homely, traditional Hiroko but also becomes attractive to Teruo’s sister Ikuko (Toshiko Iizuka) and the modern girl Satoko (Satoko Date).

Both Hiroko and Ikuko are attracted to Okajima because of his traditional masculinity in his capacity to protect them. Ikuko, rejecting a suitor who eventually exposes a problematic side to male dominance, tells him that she won’t consider anyone who’s not skilled in kendo because she is looking for a protector. He reminds her that’s what the police and the law are for, so she tells him fair enough, she’ll marry a policeman. Modernity codes “protection” into the system, depersonalised and in other ways perhaps problematic, where traditionalism relies on access to male strength. Ikuko disliked Okajima when he had a beard, but secretly desires those very qualities the beard was set to represent.

Satoko, meanwhile, the modern girl, rejected Okajima because of his bizarre appearance while he rejects her for the same reason in a mirroring of the various ways we are the image we present. Kimono’d Hiroko is good, modern girl Satoko is bad. Even after shaving his beard, Okajima remains an undercover traditionalist, wearing his kendo clothes under his suit and chivalrous to the end. Not recognising him and possibly in the pay of Teruo trying to put his sister off marriage, Satoko seduces the clean shaven Okajima while he rejects her advances but tries to “save” her from an excess of modernity by getting her away from the gang. She fancies herself in love with him, but what he does is free her from the false image of the modern society to give her back the true freedom of her own agency. In the end he chooses the classically nice, middle of the road option in remaining with Hiroko who loved him with beard and without rather than modern girl Satoko or snooty aristocrat Ikuko. You trim it but it just keeps growing back, the final title card adds, but the message seems to be that too much of one thing be it nationalistic conservatism or hedonistic modernity is no good. The middle way it is, slow and steady and as wholesome as could be.

Currently streaming in the UK via BFI Player as part of Japan 2020. Also available to stream in the US via Criterion Channel.