By 1970, Japan had more or less cemented its economic miracle and in terms of cinema at least memories of the war were beginning to recede with the young keen to address other concerns such as dissatisfaction with increasing consumerism or resistance towards American foreign policy in Asia. Unjustly neglected by international scholars, Kei Kumai by contrast refused to turn away from issues others might have found taboo or at least unpleasant enough to avoid mentioning. Like A Chain of Islands, Apart of From Life (地の群れ, Chi no Mure) has an overt anti-American sentiment but in essence criticises a society in which people are dying of guilt and shame though essentially blameless while those marginalised continue to oppress each other and fight amongst themselves rather than unite to resist their marginalisation.

Based on a novel by Mitsuharu Inoue, the film opens with a brief prologue set in 1941 before jumping forward to the mid-1960s in the naval port town of Sasebo, the naval facilities now operated by American forces. An ensemble drama, the tale revolves around a drunken doctor, Unan (Mizuho Suzuki), though this one is far from an angel merely another wounded and compromised soul of the post-war era wracked by guilt over his various moral failures which began with the incident in the prologue in which he attempted to weasel out of his responsibility after getting an ethnically Korean girl pregnant as a young teenager working in a coal mine. He is the first of many to insist “I know nothing” that he’s “responsible for nothing” firstly denying the child is his then trying to smooth it over with money before coldly telling the woman’s sister to take her to a hospital in nearby Sasebo where no one will know them in order to get an abortion and avoid the social stigma of unwed pregnancy. The sister can only look at him with contempt. Later he discovers that the young woman lost her life while trying to provoke a miscarriage.

Hako died, in a sense, out of shame. Many of Unan’s patients face the possibility of something similar. One woman comes to him about her teenage daughter, Yoshiko, who is bleeding continuously as if constantly menstruating. Unan asks the mother if she was in Nagasaki at the time of the atomic bombing as the symptoms are similar to the effects of the radiation poisoning he observed while working as a doctor in the city. She continues to deny it, but flashbacks to conversations with her now absent husband and daughter suggest she may not be telling the truth at least in its entirety even though her daughter’s life is at stake. She doesn’t want to be associated with “those Kaito Shinden people”, referring to the industrial slumland where many refugees from Nagasaki have settled which is treated as a kind of plague town by the rest of the local area. If her daughter survives but is unmasked as a second generation A-bomb victim her mother fears she will never be able to marry and that she will have “no future”.

Yet they are not the only ones facing marginalisation. A young woman, Tokuko, comes to Unan’s office wanting a certificate that proves she has been raped, but Unan doesn’t help her firstly for the understandable reason that she is, understandably, unable to explain the exact circumstances to him, and secondly because he just isn’t very invested in her wellbeing bizarrely suggesting she come back with a relative or the person responsible. As she later explains, the rapist threatened to expose the fact that her family are burakumin in order to keep her quiet while she clearly remembers that he wore a glove on his left hand which she believes probably hides a distinctive keloid skin lesion marking him as an A-bomb victim and probable resident of Kaito Shinden. Tokuko’s father had also been a victim of workplace discrimination presumably because of his burakumin heritage, his wife told that he had stabbed himself while confronting the workers who were harassing him advised to keep quiet rather than attract the attention of the authorities. Tokuko is originally shamed into silence not by her violation but by her marginalisation, later deciding to track down her assailant by herself after someone else reports the crime to the police who arrest a local Kaito Shinden troublemaker and attempt to frame him for the crime.

The confrontation however leads to a small war between the Kaito Shinden A-bomb survivors and the burakumin community which results in the death of a burakimin woman after they tactlessly insist that Kaito Shinden is a buraku below the buraku and that their blood is “rotten” and will be for generations. Discussing the case, some had even suggested that the rape was itself a result of prejudice towards the A-bomb survivors seeing as they are unable to find wives. Yet Tokuko’s mother had asked if being burakumin means it’s OK to rape her daughter, in much the same way Hako’s sister might have asked if being ethnically Korean made it OK for Unan to so casually discard her. Explaining that the locals regard Kaito Shinden as a “sick village” Yoshiko’s mother says she doesn’t think the people there are any different from anyone else despite her determination not to be associated with the A-bomb “disease”. “If Kaito Shinden is sick, the whole of Japan is sick!” Unan fires back revealing that he himself was also in Nagasaki shortly after the bomb dropped, apparently objecting to these baseless prejudices but seemingly unwilling to cure them even while his patients quite literally die of shame.

In his own case, however, it’s not prejudice or wartime trauma that have led to Unan’s alcoholism but his many moral failures and their resulting guilt. His wife (Noriko Matsumoto) wants to divorce him, partly because of the drinking, but also because of his longstanding guilt over the death of a friend who retreated to the mountains with the communists during the Red Purge of the early 1950s of whom he is also jealous in that he was previously his wife’s lover and he can’t get over wondering if he’d lived his wife would have chosen him. Guilt over Hako, perhaps mixed with the fears of his radiation exposure, have also led him to emotionally blackmail his wife into several abortions as if he thinks it improper to father a child.

Meanwhile, we seem to see pregnant women everywhere. Nobuo (Mugihito), orphaned by the A-bomb, sees a pair of them walking ahead of a gaggle of nuns which he later decides to freak out by creepily staring at them before lunging wildly like a dog among geese. The film’s conclusion finds him on the run from a gang of burakumin boys looking for revenge, running far out of the slums into the suburbs and through one of those nice new danchi housing complexes where a row of pregnant housewives sits silently knitting, something almost creepy in the vacant way they smile at him as he runs past before tripping over a child’s toy car. Boys like Nobuo are it seems cast out from the newly consumerist society of the economic miracle while just about everyone is in some way marginalised and in some cases several times over: rape victim, burakumin, A-bomb survivor, troublemaker, orphan, divorcee, communist, Christian. Nobuo wonders why God chose Nagasaki for an A-bomb when it’s where all the Christians live while the head of a Virgin Mary statue is repeatedly smashed as if to imply there’s no more mercy to be found here.

Kumai regularly cuts back to a disturbing visual motif of a cage filled with rats who kill a live chicken and fight over the scraps of rotting meat until ignited by a gust of fire, the survivors scrabbling over each other blindly looking for an exit. Meanwhile, US jet planes fly constantly overhead and all Unan can think to do is throw a rock at a flag flying on the base. “She was killed by everybody” Tokuko exclaims of the burakumin woman, suddenly seeing the webs of prejudice, oppression, and selfishness which created the circumstances which led to her death by stoning. Shot in a crisp black and white and academy ratio, Kumai’s steely drama lets no one off the hook implying that all of Japan is indeed “sick” wilfully leaving these marginalised people to fight amongst themselves for the scraps of a newly prosperous society.

DVD release trailer (no subtitles)

Yukio Mishima’s Temple of the Golden Pavilion has become one of his most representative works and seems to be one of those texts endlessly reinterpreted by each new generation. Previously adapted for the screen by Kon Ichikawa under the title of

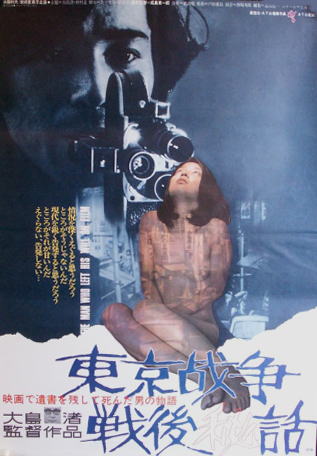

Yukio Mishima’s Temple of the Golden Pavilion has become one of his most representative works and seems to be one of those texts endlessly reinterpreted by each new generation. Previously adapted for the screen by Kon Ichikawa under the title of  Every story is a ghost story in a sense. In every photograph there’s a presence which cannot be seen but is always felt. The filmmaker is a phantom and an enigma, but can we understand the spirit from what we see? Whose viewpoint are seeing, and can we ever separate that subjective vision from the one we create for ourselves within our own minds? The Man Who Left his Will on Film (東京戰争戦後秘話, Tokyo Senso Sengo Hiwa) is an oblique examination of identity but more specifically how that identity is repurposed through cinema as cinema is repurposed as a political weapon.

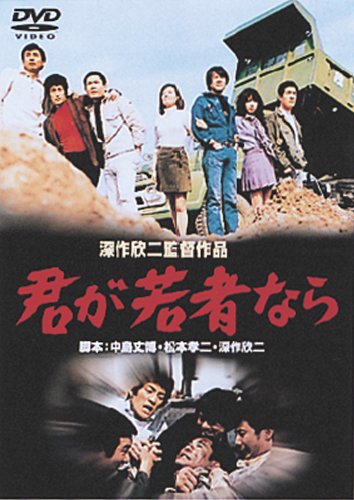

Every story is a ghost story in a sense. In every photograph there’s a presence which cannot be seen but is always felt. The filmmaker is a phantom and an enigma, but can we understand the spirit from what we see? Whose viewpoint are seeing, and can we ever separate that subjective vision from the one we create for ourselves within our own minds? The Man Who Left his Will on Film (東京戰争戦後秘話, Tokyo Senso Sengo Hiwa) is an oblique examination of identity but more specifically how that identity is repurposed through cinema as cinema is repurposed as a political weapon. For 1970’s If You We’re Young: Rage (君が若者なら, Kimi ga Wakamono Nara), Fukasaku returns to his most prominent theme – disaffected youth and the lack of opportunities afforded to disadvantaged youngsters during the otherwise booming post-war era. Like the more realistic gangster epics that were to come, Fukasaku laments the generation who’ve been sold an unattainable dream – come to the city, work hard, make a decent life for yourself. Only what the young men find here is overwork, exploitation and a considerably decreased likelihood of being able to achieve all they’ve been promised.

For 1970’s If You We’re Young: Rage (君が若者なら, Kimi ga Wakamono Nara), Fukasaku returns to his most prominent theme – disaffected youth and the lack of opportunities afforded to disadvantaged youngsters during the otherwise booming post-war era. Like the more realistic gangster epics that were to come, Fukasaku laments the generation who’ve been sold an unattainable dream – come to the city, work hard, make a decent life for yourself. Only what the young men find here is overwork, exploitation and a considerably decreased likelihood of being able to achieve all they’ve been promised. The second film contained within Arrow’s Kiju Yoshida boxset is perhaps his least accessible. Ostensibly, Heroic Purgatory (煉獄エロイカ, Rengoku Eroika) is an examination of leftist politics in the years surrounding the renewal of the hugely controversial mutual security pact between Japan and America. However, it quickly disregards any kind of narrative sense as time periods blur so finely as to leave us with no objective “now” to belong to and characters switch identities with no warning or discernible reason. Yoshida is not really after objective truth here – there is no truth in cinema, film lies repeatedly until it finally exposes the truth.

The second film contained within Arrow’s Kiju Yoshida boxset is perhaps his least accessible. Ostensibly, Heroic Purgatory (煉獄エロイカ, Rengoku Eroika) is an examination of leftist politics in the years surrounding the renewal of the hugely controversial mutual security pact between Japan and America. However, it quickly disregards any kind of narrative sense as time periods blur so finely as to leave us with no objective “now” to belong to and characters switch identities with no warning or discernible reason. Yoshida is not really after objective truth here – there is no truth in cinema, film lies repeatedly until it finally exposes the truth.