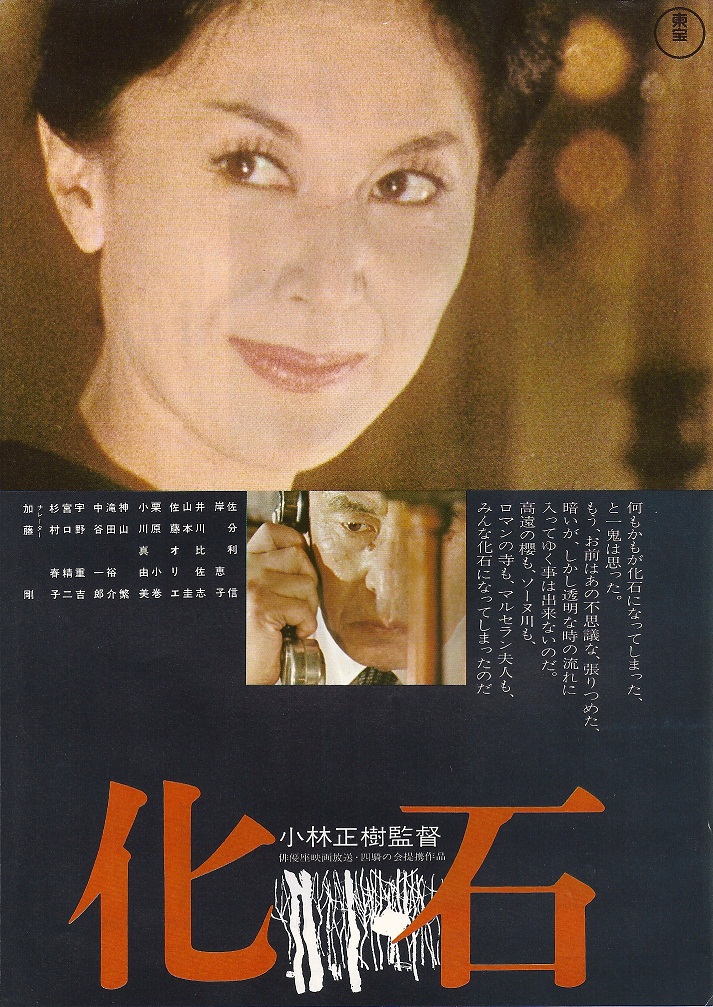

Throughout Masaki Kobayashi’s relatively short career, his overriding concern was the place of the conscientious individual within a corrupt society. Perhaps most clearly seen in his magnum opus, The Human Condition, Kobayashi’s humanist ethos was one of rigid integrity in which society’s faults must be spoken and addressed in service of creating a better, fairer world. As might be expected, his often raw, angry social critiques were not always what studios were looking for, especially heading into the “difficult” 1970s which saw mainstream production houses turning on the sleaze to increase potential box office. Reluctantly, Kobayashi headed to TV on the condition he could retain some of his footage for a feature film. Adapted from the 1965 novel by Yasushi Inoue, The Fossil (化石, Kaseki) revisits many of Kobayashi’s recurrent themes only in a quieter, more contemplative way as an apparently successful man prepares to enter the final stages of his life, wondering if this is all there really is.

Throughout Masaki Kobayashi’s relatively short career, his overriding concern was the place of the conscientious individual within a corrupt society. Perhaps most clearly seen in his magnum opus, The Human Condition, Kobayashi’s humanist ethos was one of rigid integrity in which society’s faults must be spoken and addressed in service of creating a better, fairer world. As might be expected, his often raw, angry social critiques were not always what studios were looking for, especially heading into the “difficult” 1970s which saw mainstream production houses turning on the sleaze to increase potential box office. Reluctantly, Kobayashi headed to TV on the condition he could retain some of his footage for a feature film. Adapted from the 1965 novel by Yasushi Inoue, The Fossil (化石, Kaseki) revisits many of Kobayashi’s recurrent themes only in a quieter, more contemplative way as an apparently successful man prepares to enter the final stages of his life, wondering if this is all there really is.

Itsuki (Shin Saburi), a selfmade man who hit it big in Japan’s post-war boom town by founding his own construction firm which currently employs over 1000 people, is about to catch a plane to Europe for a trip that’s pleasure disguised as business. As he leaves, his younger daughter informs him he may be about to become a grandfather for the second time after the birth of her niece, though she is worried and is not sure she wanted a child at this precise moment. Brushing aside her nervousness with an odd kind of fatherly warmth, Itsuki seems pleased and states that he hopes it’s a boy this time. Nevertheless he leaves abruptly to catch his plane. During the flight he begins to become depressed, reflecting that since his wife has died and both of his daughters have married and have (or are about to have) children of their own he is now totally alone. Never before has he faced a sensation of such complete existential loneliness, and his arrival in Paris proves far less invigorating than he had originally hoped.

Wandering around with his secretary, Funazu (Hisashi Igawa), who has accompanied him on this “business” trip, Itsuki catches sight of an elegant Japanese woman in a local park and is instantly captivated. Improbably spotting the same woman several times during his stay, Itsuki later discovers that she is the wife of a local dignitary though not universally liked in the Japanese ex-pat community. At this same work dinner where he discusses the merits of Madame Marcelin (Keiko Kishi), Itsuki experiences a severe pain in his abdomen which makes it difficult for him to stand. Feeling no better back at the hotel, Funazu arranges a doctor’s visit for him. The doctors seem to think he should head straight home which Itsuki is not prepared to do but when he masquerades as Funazu on the phone to get the full verdict, he finds out it’s most likely inoperable intestinal cancer and he may only have a year or so to live.

This unexpected – or, perhaps half sensed, news sends him into a numbing cycle of panic and confusion. At this point Itsuki begins his ongoing dialogue with the mysterious woman, arriving in the guise of Madame Marcelin only dressed in the traditional black kimono of mourning. Telling no one, Itsuki embarks on a contemplative journey in preparation for a union with his dark lady in waiting which takes him from the Romanesque churches of the picturesque French countryside back to Japan and the emptiness, or otherwise, of his settled, professionally successful life.

Like the hero of Kurosawa’s similarly themed Ikiru, Itsuki’s profound discovery is that his overwhelming need for personal validation through work has led him to neglect human relationships and may ultimately have been misplaced. On his return to Japan, Itsuki makes the extremely unusual decision to take a day off only to receive a phone call regarding an old friend and former colleague who, coincidentally, has aggressive cancer and has been asking to see him. Not wanting to mention his own illness, Itsuki parts with his friend feeling it may be for the last time but eventually returns for a deeper conversation in which he probes him for his views about his life so far and what he would do if he had, say, another year to live. His friend has come to the same conclusion, that his working life has largely been a waste of time. What he’d do differently he couldn’t rightly say, things are as they are, but if he had more time he’d want to do “good” in the world, make a positive change and live for something greater than himself.

Itsuki isn’t quite as taken with the idea of “goodness” as a life principle, though he does begin to re-examine himself and the way he has treated the people in his life from apologising to the stepmother he failed to bond with as a child to reconnecting with an old army buddy who maybe the closest thing he’s ever had to a “true friendship” – something which the mysterious woman reminded him he’d been missing for a very long time. Meeting Teppei again, Itsuki is introduced to his walls of fossilised coral and all of their millions of years of history frozen into one indivisible moment. Feeling both infinite and infinitesimal, Itsuki is reminded of his immediate post-war moment of survivor’s guilt in which he and his friend agreed that they’ve each been living on borrowed time ever since.

Given a sudden and unexpected chance of reprieve, Itsuki is even more confounded than before. Having made a friend of death, he may now have to learn to live again, even if his mysterious lady reminds him that she will always be with him, even if he can no longer see her. Though he’d wanted nothing more than to live to see the cherry blossoms in the company of the living Madame Marcelin whose vision it was that so captivated him, his old life is one he cannot return to and must be preserved in amber, frozen and perfect like Teppei’s fossilised coral.

Tonally European, perhaps taking inspiration from Death in Venice, and bringing in a Christianising moral viewpoint pitting the values of honest hard work against genuine human feeling, The Fossil is the story of a man realising he has been sentenced to death, as we all have, and makes his peace with it only to learn that perhaps his sentence will be suspended. Yet for a time death was his friend and her absence is a void which cannot be filled. This life, this new life so unexpectedly delivered, must be lived and lived to the full. Itsuki, who had prepared himself to die must now learn to live and to do so in a way which fulfils his own soul. Originally filmed as a 13 part TV series now reduced to three hours and twenty minutes, The Fossil’s only consolation to its medium is in its 4:3 frame which Kobayashi’s unobtrusive style fully embraces with its ominous distance shots, slow zooms and eerie pans backed up by Toru Takemitsu’s sombre score. Kobayashi, who’d given us a career dedicated to railing against the injustices of the system, suddenly gives us the ultimate rebellion – against death itself as a man who’d prepared himself to die must judge the way he’s lived on his own terms, and, finding himself wanting, learn to live in a way which better fits his personal integrity.

Yasuzo Masumura is best remembered for his deliberately transgressive, often shockingly grotesque critiques of Japanese society and its conformist overtones. Lullaby of the Earth (大地の子守歌, Daichi no Komoriuta) is one of his few completely independent features, filmed after the bankruptcy of Daiei where Masumura had spent the bulk of his early years. As such, it is quite an exception in terms of his wider career both in terms of its production and in its earthy, spiritual themes. Adapted from the 1974 novel by Kukiko Moto, Lullaby of the Earth is the story of an abandoned and betrayed woman but one who also draws her strength from the Earth itself.

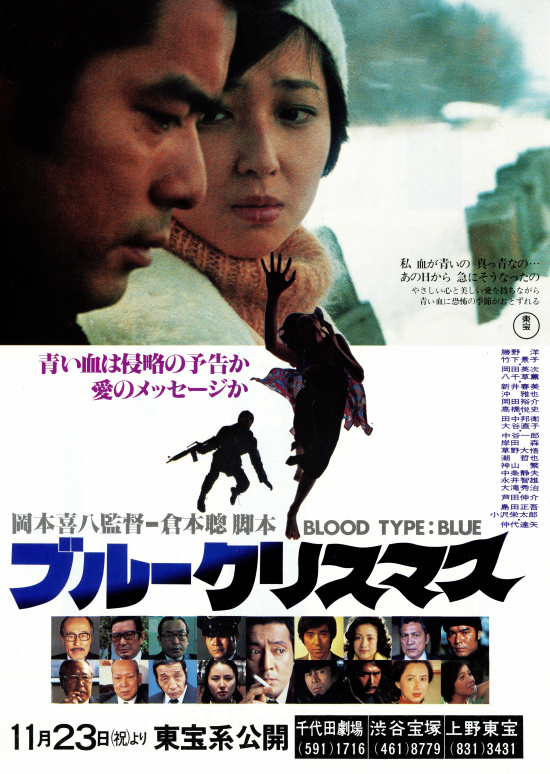

Yasuzo Masumura is best remembered for his deliberately transgressive, often shockingly grotesque critiques of Japanese society and its conformist overtones. Lullaby of the Earth (大地の子守歌, Daichi no Komoriuta) is one of his few completely independent features, filmed after the bankruptcy of Daiei where Masumura had spent the bulk of his early years. As such, it is quite an exception in terms of his wider career both in terms of its production and in its earthy, spiritual themes. Adapted from the 1974 novel by Kukiko Moto, Lullaby of the Earth is the story of an abandoned and betrayed woman but one who also draws her strength from the Earth itself. The Christmas movie has fallen out of fashion of late as genial seasonally themed romantic comedies have given way to sci-fi or fantasy blockbusters. Perhaps surprisingly seeing as Christmas in Japan is more akin to Valentine’s Day, the phenomenon has never really taken hold meaning there are a shortage of date worthy movies designed for the festive season. If you were hoping Blue Christmas (ブルークリスマス) might plug this gap with some romantic melodrama, be prepared to find your heart breaking in an entirely different way because this Kichachi Okamoto adaptation of a So Kuramoto novel is a bleak ‘70s conspiracy thriller guaranteed to kill that festive spirit stone dead.

The Christmas movie has fallen out of fashion of late as genial seasonally themed romantic comedies have given way to sci-fi or fantasy blockbusters. Perhaps surprisingly seeing as Christmas in Japan is more akin to Valentine’s Day, the phenomenon has never really taken hold meaning there are a shortage of date worthy movies designed for the festive season. If you were hoping Blue Christmas (ブルークリスマス) might plug this gap with some romantic melodrama, be prepared to find your heart breaking in an entirely different way because this Kichachi Okamoto adaptation of a So Kuramoto novel is a bleak ‘70s conspiracy thriller guaranteed to kill that festive spirit stone dead. “Sometimes it feels good to risk your life for something other people think is stupid”, says one of the leading players of Masaki Kobayashi’s strangely retitled Inn of Evil (いのちぼうにふろう, Inochi Bonifuro), neatly summing up the director’s key philosophy in a few simple words. The original Japanese title “Inochi Bonifuro” means something more like “To Throw One’s Life Away”, which more directly signals the tragic character drama that’s about to unfold. Though it most obviously relates to the decision that this gang of hardened criminals is about to make, the criticism is a wider one as the film stops to ask why it is this group of unusual characters have found themselves living under the roof of the Easy Tavern engaged in benign acts of smuggling during Japan’s isolationist period.

“Sometimes it feels good to risk your life for something other people think is stupid”, says one of the leading players of Masaki Kobayashi’s strangely retitled Inn of Evil (いのちぼうにふろう, Inochi Bonifuro), neatly summing up the director’s key philosophy in a few simple words. The original Japanese title “Inochi Bonifuro” means something more like “To Throw One’s Life Away”, which more directly signals the tragic character drama that’s about to unfold. Though it most obviously relates to the decision that this gang of hardened criminals is about to make, the criticism is a wider one as the film stops to ask why it is this group of unusual characters have found themselves living under the roof of the Easy Tavern engaged in benign acts of smuggling during Japan’s isolationist period. Ogami (Tomisaburo Wakayama) and his son Daigoro (Akihiro Tomikawa) have been following the Demon Way for five films, chasing the elusive Lord Retsudo (Minoru Oki) of the villainous Yagyu clan who was responsible for the murder of Ogami’s wife and his subsequent framing for treason. The Demon Way is never easy, and Ogami has committed himself to following it to its conclusion, but recent encounters have broadened a conflict in his heart as innocents and seekers of justice have died alongside guilty men and cowards. Lone Wolf and Cub: White Heaven in Hell (子連れ狼 地獄へ行くぞ!大五郎, Kozure Okami: Jigoku e Ikuzo! Daigoro) moves him closer to his target but also further deepens his descent into the underworld as he’s forced to confront the wake of his ongoing quest for vengeance.

Ogami (Tomisaburo Wakayama) and his son Daigoro (Akihiro Tomikawa) have been following the Demon Way for five films, chasing the elusive Lord Retsudo (Minoru Oki) of the villainous Yagyu clan who was responsible for the murder of Ogami’s wife and his subsequent framing for treason. The Demon Way is never easy, and Ogami has committed himself to following it to its conclusion, but recent encounters have broadened a conflict in his heart as innocents and seekers of justice have died alongside guilty men and cowards. Lone Wolf and Cub: White Heaven in Hell (子連れ狼 地獄へ行くぞ!大五郎, Kozure Okami: Jigoku e Ikuzo! Daigoro) moves him closer to his target but also further deepens his descent into the underworld as he’s forced to confront the wake of his ongoing quest for vengeance. Ogami (Tomisaburo Wakayama), former Shogun executioner now a fugitive in search of justice after being framed for treason by the villainous Yagyu clan who are also responsible for the death of his wife, is still on the Demon’s Way with his young son Daigoro (Akihiro Tomikawa). Five films into this six film cycle, the pair are edging closer to their goal as the evil Lord Retsudo continues to make shadowy appearances at the corners of their world. However, the Demon’s Way carries a heavy toll, littered with corpses of unlucky challengers, the road has, of late, begun to claim the lives of the virtuous along with the venal. Conflicted as he was in his execution of a contract to assassinate the tragic Oyuki in the previous instalment,

Ogami (Tomisaburo Wakayama), former Shogun executioner now a fugitive in search of justice after being framed for treason by the villainous Yagyu clan who are also responsible for the death of his wife, is still on the Demon’s Way with his young son Daigoro (Akihiro Tomikawa). Five films into this six film cycle, the pair are edging closer to their goal as the evil Lord Retsudo continues to make shadowy appearances at the corners of their world. However, the Demon’s Way carries a heavy toll, littered with corpses of unlucky challengers, the road has, of late, begun to claim the lives of the virtuous along with the venal. Conflicted as he was in his execution of a contract to assassinate the tragic Oyuki in the previous instalment,  Now four instalments into the Lone Wolf and Cub series, Ogami (Tomisaburo Wakayama) and Daigoro (Akihiro Tomikawa) have been on the road for quite some time, seeking vengeance against the Yagyu clan who framed Ogami for treason, murdered his wife, and stole his prized position as the official Shogun executioner. Lone Wolf and Cub: Baby Cart in Peril (子連れ狼 親の心子の心, Kozure Okami: Oya no Kokoro Ko no Kokoro) is the first in the series not to be directed by Kenji Misumi (though he would return for the following chapter) and the change in approach is very much in evidence as veteran Nikkatsu director Buichi Saito picks up the reins and takes things in a much more active, full on ‘70s exploitation direction. Where

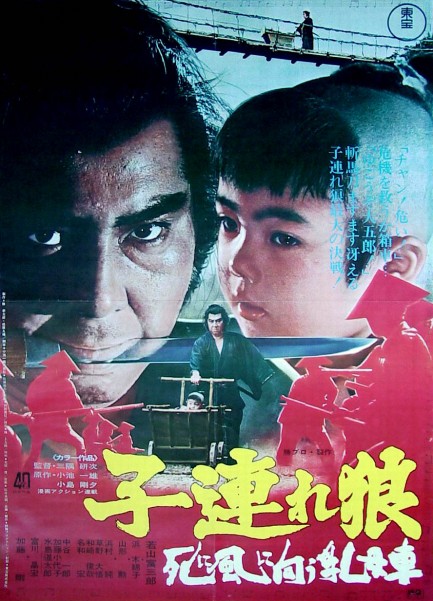

Now four instalments into the Lone Wolf and Cub series, Ogami (Tomisaburo Wakayama) and Daigoro (Akihiro Tomikawa) have been on the road for quite some time, seeking vengeance against the Yagyu clan who framed Ogami for treason, murdered his wife, and stole his prized position as the official Shogun executioner. Lone Wolf and Cub: Baby Cart in Peril (子連れ狼 親の心子の心, Kozure Okami: Oya no Kokoro Ko no Kokoro) is the first in the series not to be directed by Kenji Misumi (though he would return for the following chapter) and the change in approach is very much in evidence as veteran Nikkatsu director Buichi Saito picks up the reins and takes things in a much more active, full on ‘70s exploitation direction. Where  Ogami Itto (Tomisaburo Wakayama) and his (slightly less) young son Daigoro (Akihiro Tomikawa) are going to hell in a baby cart in this third instalment of the six film series, Lone Wolf and Cub: Baby Cart to Hades (子連れ狼 死に風に向う乳母車, Kozure Okami: Shinikazeni Mukau Ubaguruma). The former shogun executioner, framed for treason by the villainous Yagyu clan intent on assuming his position, is still on the “Demon’s Way”, seeking vengeance and the restoration of his clan’s honour with his toddler son safely ensconced within a bamboo cart which also holds its fair share of secrets. In the previous chapter,

Ogami Itto (Tomisaburo Wakayama) and his (slightly less) young son Daigoro (Akihiro Tomikawa) are going to hell in a baby cart in this third instalment of the six film series, Lone Wolf and Cub: Baby Cart to Hades (子連れ狼 死に風に向う乳母車, Kozure Okami: Shinikazeni Mukau Ubaguruma). The former shogun executioner, framed for treason by the villainous Yagyu clan intent on assuming his position, is still on the “Demon’s Way”, seeking vengeance and the restoration of his clan’s honour with his toddler son safely ensconced within a bamboo cart which also holds its fair share of secrets. In the previous chapter,  The first instalment of the

The first instalment of the  When it comes to period exploitation films of the 1970s, one name looms large – Kazuo Koike. A prolific mangaka, Koike also moved into writing screenplays for the various adaptations of his manga including the much loved Lady Snowblood and an original series in the form of Hanzo the Razor. Lone Wolf and Cub was one of his earliest successes, published between 1970 and 1976 the series spanned 28 volumes and was quickly turned into a movie franchise following the usual pattern of the time which saw six instalments released from 1972 to 1974. Martial arts specialist Tomisaburo Wakayama starred as the ill fated “Lone Wolf”, Ogami, in each of the theatrical movies as the former shogun executioner fights to clear his name and get revenge on the people who framed him for treason and murdered his wife, all with his adorable little son ensconced in a bamboo cart.

When it comes to period exploitation films of the 1970s, one name looms large – Kazuo Koike. A prolific mangaka, Koike also moved into writing screenplays for the various adaptations of his manga including the much loved Lady Snowblood and an original series in the form of Hanzo the Razor. Lone Wolf and Cub was one of his earliest successes, published between 1970 and 1976 the series spanned 28 volumes and was quickly turned into a movie franchise following the usual pattern of the time which saw six instalments released from 1972 to 1974. Martial arts specialist Tomisaburo Wakayama starred as the ill fated “Lone Wolf”, Ogami, in each of the theatrical movies as the former shogun executioner fights to clear his name and get revenge on the people who framed him for treason and murdered his wife, all with his adorable little son ensconced in a bamboo cart.