Shinji Somai is not particularly well known outside of Japan but where his work is celebrated it’s mostly for his youth films of teen alienation and pop culture cool. Released in the same year as his iconic Typhoon Club, Love Hotel (ラブホテル) seems like something of an aberration in Somai’s career which leans towards the melancholic rather than the passionate. Somai had begun his working life apprenticing with Nikkatsu during their Roman Porno years and Love Hotel is, in someways, a return to this genre but is only accidentally a “pink film”, produced with Director’s Company and later acquired by the pink film giant. As such it contains a number of explicit sex scenes but maintains Somai’s characteristic long takes and contemplative approach rather than adhering to the often formulaic nature of the Roman Porno.

Failed businessman Muraki (Minori Terada) returns one day to find his office full of gangsters in the middle of raping his wife. Distraught, his first thought is suicide but then he decides on a little roundabout revenge before he goes. Dressed in a dark suit and sunglasses like some ‘60s Nikkatsu bad guy, Muraki holes up in a love hotel and calls down for a girl. “Yumi” (Noriko Hayami) arrives not long after. Handing the girl a vast sum of money, Muraki then instructs her to close her eyes because he’s also brought “a present”. He handcuffs her and reveals his true purpose by tearing off her clothes, tying her up and fitting her with a vibrator. He’s going to kill himself tonight, but he doesn’t want to go alone. In the end, he can’t go through with it, something in Yumi’s face changes his mind and he leaves her there, tied up and handcuffed.

Two years later, Muraki has divorced his wife (apparently to keep her safe from the yakuza who are still after him for his debts) and is now living an intentionally dull life as a taxi driver. One fateful day he runs into Yumi again, only she’s no longer “Yumi” but “Nami”, an office lady at a top company. Eventually recognising each other, the pair are each forced to face the circumstances surrounding the traumatic night of two years previously but doing so means risking everything they have now.

Love Hotel is a film of seeing and not seeing, of looking and refusal to look. The film opens with a semi-explicit sexual scene in which Muraki’s wife is raped by a loanshark in which we watch both Muraki’s horrified expression and the act itself by means of a well positioned mirror. Somai repeats the mirroring motif throughout the film both by showing us Nami repeatedly caught in mirrors and by the obvious tripartite glass arrangement of the love hotel’s headboard. Both Muraki and Nami have elements of themselves at which they’d rather not look but the ever present mirrors constantly prompt them into areas of self-reflection, ironically possible only by looking at the other.

Where Muraki has chosen a life of austerity, separating from his wife who nevertheless continues stopping by to look after him in all of the wifely ways, Nami has tried and failed to put her traumatic past behind her by hopping into the consumerist revolution. Having supported herself through prostitution as a student, she’s managed to swing a pretty good job at top company only to find herself “prostituted” again through an ill-advised affair with her married boss. After his wife finds out and Nami loses her job and the entire life she’d begun to build for herself, she tries to call her former lover for consolation only to have him cruelly hang up on her. Nami continues her lamentations to the alarming trill of the dial tone in a heartbreaking moment of true loneliness.

Left with nothing else, the pair decide to revisit their unfinished love hotel business but their much more normal encounter changes each of them in different ways. It’s clear something has passed between the two, but Muraki’s final glance into the mirror perhaps shows him something he’d rather not have seen. Nami’s face, like Yumi’s face, may well have been “angelic” but cannot “save” Muraki in the same way twice – or at least, not in the way the restored Nami would have liked to save him. Dark, melancholy and fatalistic, Somai’s stab at Roman Porno is a sad tale of frustrated love, destroyed by the use and misuse of bodies speaking against each other and becoming a barrier to true connection. The Love Hotel is a place romance goes to die, and what the pair of damaged lovers at the centre of his noir-tinged tale of despair find there is only emptiness and pain devoid of any sign of hope.

Opening scene (no subtitles)

Masterfully constructed one take final scene (dialogue free)

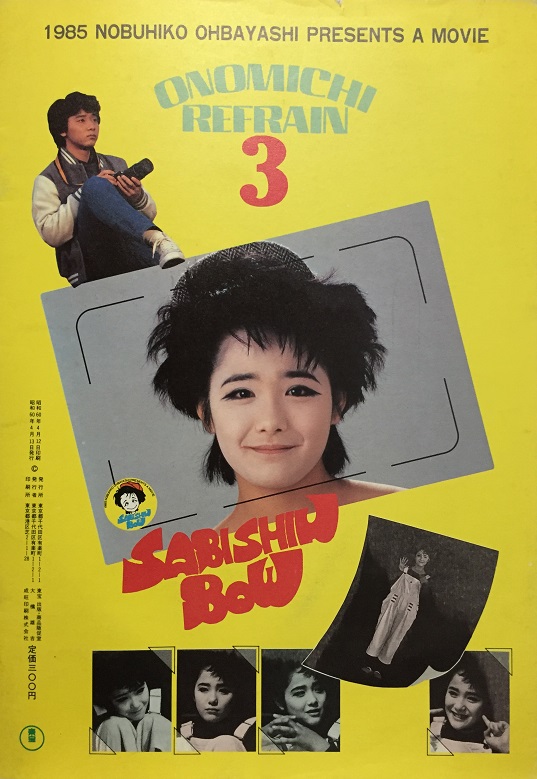

Miss Lonely (さびしんぼう, Sabishinbou, AKA Lonelyheart) is the final film in Obayashi’s Onomichi Trilogy all of which are set in his own hometown of Onomichi. This time Obayashi casts up and coming idol of the time, Yasuko Tomita, in a dual role of a reserved high school student and a mysterious spirit known as Miss Lonely. In typical idol film fashion, Tomita also sings the theme tune though this is a much more male lead effort than many an idol themed teen movie.

Miss Lonely (さびしんぼう, Sabishinbou, AKA Lonelyheart) is the final film in Obayashi’s Onomichi Trilogy all of which are set in his own hometown of Onomichi. This time Obayashi casts up and coming idol of the time, Yasuko Tomita, in a dual role of a reserved high school student and a mysterious spirit known as Miss Lonely. In typical idol film fashion, Tomita also sings the theme tune though this is a much more male lead effort than many an idol themed teen movie. Nobuhiko Obayashi takes another trip into the idol movie world only this time for Toho with an adaptation of a popular shojo manga. That is to say, he employs a number of idols within the film led by Toho’s own Yasuko Sawaguchi, though the film does not fit the usual idol movie mould in that neither Sawaguchi or the other girls is linked with the title song. Following something of a sisterly trope which is not uncommon in Japanese film or literature, Four Sisters (姉妹坂, Shimaizaka) centres around four orphaned children who discover their pasts, and indeed futures, are not necessarily those they would have assumed them to be.

Nobuhiko Obayashi takes another trip into the idol movie world only this time for Toho with an adaptation of a popular shojo manga. That is to say, he employs a number of idols within the film led by Toho’s own Yasuko Sawaguchi, though the film does not fit the usual idol movie mould in that neither Sawaguchi or the other girls is linked with the title song. Following something of a sisterly trope which is not uncommon in Japanese film or literature, Four Sisters (姉妹坂, Shimaizaka) centres around four orphaned children who discover their pasts, and indeed futures, are not necessarily those they would have assumed them to be. Akira Kurosawa is arguably the most internationally well known Japanese director – after all, Seven Samurai is the one “foreign film” everyone who “doesn’t do subtitles” has seen. Though he’s often thought of as being quintessentially Japanese, his fellow countryman often regarded him as too Western in terms of his filming style. They may have a point when you consider that he made three different movies inspired by the works of Shakespeare (The Bad Sleep Well – Hamlet, Throne of Blood – Macbeth, and Ran – King Lear) though in each case it’s clear that “inspired” is very much the right word for these very liberal treatments.

Akira Kurosawa is arguably the most internationally well known Japanese director – after all, Seven Samurai is the one “foreign film” everyone who “doesn’t do subtitles” has seen. Though he’s often thought of as being quintessentially Japanese, his fellow countryman often regarded him as too Western in terms of his filming style. They may have a point when you consider that he made three different movies inspired by the works of Shakespeare (The Bad Sleep Well – Hamlet, Throne of Blood – Macbeth, and Ran – King Lear) though in each case it’s clear that “inspired” is very much the right word for these very liberal treatments. Yoshimitsu Morita had a long and varied career (even if it was packed into a relatively short time) which encompassed throwaway teen idol dramas and award winning art house movies but even so tackling one of the great novels by one of Japan’s most highly regarded authors might be thought an unusual move. Like a lot of his work, Natsume Soseki’s Sorekara (And Then…) deals with the massive culture clash which reverberated through Japan during the late Meiji era and, once again, he uses the idea of frustrated romance to explore the way in which the past and future often work against each other.

Yoshimitsu Morita had a long and varied career (even if it was packed into a relatively short time) which encompassed throwaway teen idol dramas and award winning art house movies but even so tackling one of the great novels by one of Japan’s most highly regarded authors might be thought an unusual move. Like a lot of his work, Natsume Soseki’s Sorekara (And Then…) deals with the massive culture clash which reverberated through Japan during the late Meiji era and, once again, he uses the idea of frustrated romance to explore the way in which the past and future often work against each other. Never one to be accused of clarity, Seijun Suzuki’s Capone Cries a Lot (カポネおおいになく, Capone Ooni Naku) is one of his most cheerfully bizarre movies coming fairly late in his career yet and neatly slotting itself in right after Suzuki’s first two Taisho era movies,

Never one to be accused of clarity, Seijun Suzuki’s Capone Cries a Lot (カポネおおいになく, Capone Ooni Naku) is one of his most cheerfully bizarre movies coming fairly late in his career yet and neatly slotting itself in right after Suzuki’s first two Taisho era movies,