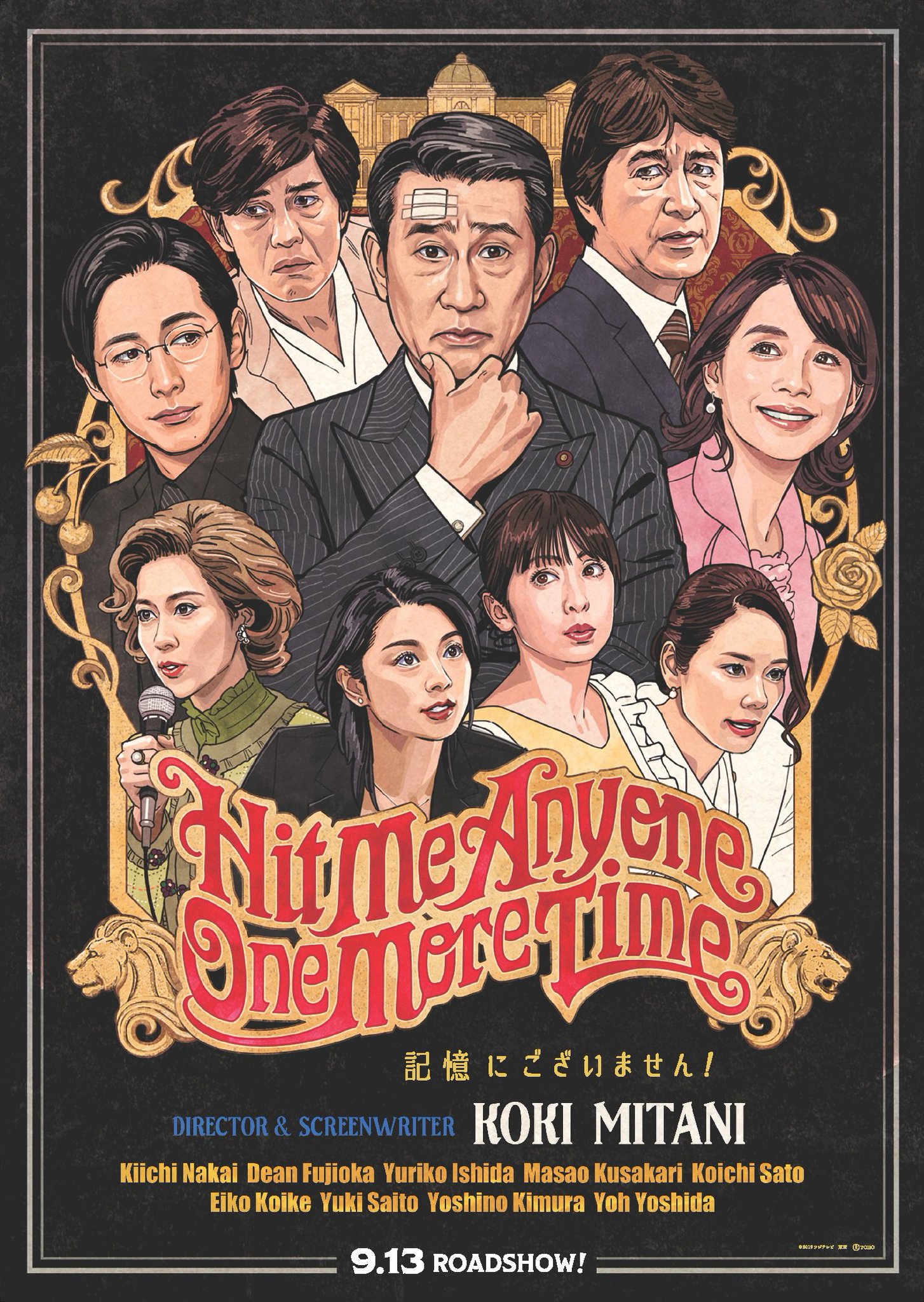

Imagine if you woke up one day and found out you’re actually the national leader of your country and not only that absolutely everyone, including your wife and son, hates you with furious intensity. The hapless protagonist of Koki Mitani’s lowkey political satire Hit Me Anyone One More Time (記憶にございません!, Kioku ni Gozaimasen!) finds himself in just this stressful situation having lost all of his memories since he made the fateful decision to enter politics, rendered infinitely naive as he tries to keep up appearances while internally conflicted by the direction both his life and his country under his stewardship seem to have taken.

Regarded as the “all-time worst prime minister” in Japanese history, Keisuke Kuroda (Kiichi Nakai) is known as a venal bore, a ghastly misogynist and all-round arsehole. To put it bluntly the very fact that a man like Kuroda could ever have become prime minster in the first place hints at a deep-seated rot in the political order. Aside from his gaffe-prone personality, the chief complaints against his administration are a sales tax hike and welfare cuts both of which target those with the least means, not that Kuroda cares very much about them. His big legacy idea is to build a second Diet building right next to the first Diet building only with spa facilities, illicitly teaming up with a childhood friend turned construction magnate who has been supplying him with hefty “donations”.

After insulting the electorate during an outdoor balcony speech, Kuroda is hit on the head by a rock thrown by a disgruntled voter. Having lost his memory he regresses to a state of innocence from before he was corrupted by the cutthroat world of Japanese politics, now a nice, polite, slightly mild-mannered man who stuns his staff with his newfound consideration for others including a widely televised moment in which he stops to help up a female reporter who trips while chasing him in the lobby. Few believe he’s really changed, assuming this is some sort of bit intended to help rehabilitate his reputation. His new attitude, however, eventually fosters a new sense of hope for political change among his previously jaded, cynical staff who had long since given up hope of building a better Japan.

Unsurprisingly, Mitani mostly avoids direct allusions to real world politics but adopts a mildly progressive stance as he sends a virtual innocent into the lion’s den of contemporary politics. It’s not long before Kuroda’s asking sensible questions about policy that wouldn’t go down so well with his (presumably) centre-right party including lowering the sales tax and raising the corporate, taking the time to greet constituents including a contingent of cherry farmers which contributes to his later decision to turn down a tariff-free trade deal for American cherries endangering diplomatic relations with the Japanese-American US President. No longer a ruthless political animal but a rueful middle-aged man who actually cares about ordinary people, Kuroda attempts to change the course Japanese politics largely by taking on the king maker, Tsurumaru (Masao Kusakari), his Chief Cabinet Secretary and the true holder of power in this infinitely corrupt political system.

All sorts of sordid politics is on display from Kuroda’s womanising and a potential blackmail plot involving his wife’s affair to Tsurumaru’s yakuza ties and an even worse secret he would find personally ruinous should it get out. The ironic Japanese title of the film takes its name from that most universal of political get out of jail free cards, “I do not recall”, Kuroda’s standard response when questioned in the Diet about any of his extremely dodgy dealings. Instructing Kuroda that he should drop this “shallow humanism”, Tsurumaru can offer only the motivation that he wants to “remain in politics for as long as possible” while discovering that his old-school methods of political manipulation may no longer work when those around him find the courage to shed their cynicism and embrace a cleaner, kinder politics.

Throwing in random gags such as a foreign minister who can’t speak English and has large ears with a pot belly that give him the appearance of Buddha while taking minor potshots as the usually toothless TV media through his series of acerbic anchors only too keen to criticise the PM live on air, Mitani’s comedy is characteristically inoffensive with its mix of slapstick and goodnatured farce but nevertheless makes a subtle plea for decent, compassionate politics which puts the interests of the people first rather than those of the governing elite.

Hit Me Anyone One More Time streamed as part of this year’s Nippon Connection.

Original trailer (English subtitles)