Figuring out who you are is a normal part of growing up, but if you start to suspect that parts of the puzzle have been kept from you it can become an even more complicated business. The hero of Ahn Ju-young’s delightfully charming debut A Boy and Sungreen (보희와 녹양, Boheewa Nokyang) thought he was doing OK. Maybe he worried that he was a little bit weedy and resented being picked on by the snooty kids at school, but he always had his good friend Nok-yang (Kim Ju-a) to hide behind and she always had his back. Realising that his mum (Shin Dong-mi) may have a new romance on the cards entirely destabilises his worldview, sends his anxiety into overdrive, and reawakens a series of as yet unresolved abandonment issues resulting from losing his father at a young age.

Figuring out who you are is a normal part of growing up, but if you start to suspect that parts of the puzzle have been kept from you it can become an even more complicated business. The hero of Ahn Ju-young’s delightfully charming debut A Boy and Sungreen (보희와 녹양, Boheewa Nokyang) thought he was doing OK. Maybe he worried that he was a little bit weedy and resented being picked on by the snooty kids at school, but he always had his good friend Nok-yang (Kim Ju-a) to hide behind and she always had his back. Realising that his mum (Shin Dong-mi) may have a new romance on the cards entirely destabilises his worldview, sends his anxiety into overdrive, and reawakens a series of as yet unresolved abandonment issues resulting from losing his father at a young age.

What Bo-hee (Ahn Ji-ho) discovers on “running away” to visit a woman he kind of remembers might be his half-sister, is that his mother might have lied to him and the father he thought was dead might actually still be alive. Together with his best friend Nok-yang, he resolves to investigate and find out if his father is still out there somewhere, if he still thinks of him, what sort of man he might be, and, crucially, why he chose to abandon his son. Still upset with his mother and childishly resentful, Bo-hee avoids going home and installs himself at his “half-sister” Nam-hee’s (Kim So-ra), an air hostess who turns out to be a cousin temporarily taken in by Bo-hee’s mum when she ran away from home as a teenager, where is he is cared for by her surprisingly supportive boyfriend Sung-wook (Seo Hyun-woo).

Tellingly, Sung-wook is also an orphan with no family, raised in an orphanage with no parental models yet easily slipping into a positive paternal role. Both Bo-hee and Nok-yang are being raised in single parent families, Bo-hee believing until recently that his father had died, while Nok-yang lost her mother in childbirth and lives with her salty grandma and distant father. In conservative Korean society they each experience a degree of stigma for not having the “full” complement of parents with some of the snooty kids at school even assuming that’s why they’re friends, but the pair largely rejoice in each other’s company and have learned to pay them no mind.

Meanwhile, Bo-hee is experiencing strange anxiety-like attacks which eventually turn out to be something more serious, but neatly underline his intense adolescent confusion. Finding out his mother has a boyfriend not only forces him to confront his father’s absence, but also deepens the sense of anxious rootlessness he feels as someone without an extended family network. As Nok-yang somewhat insensitively puts it, what if the boyfriend turns out to be an “evil stepmother” and pushes him out of his family home, where will he go then? That kind of thinking is what leads him to track down Nam-hee, “certain” that she won’t turn him away because, he believes, they share the same father.

Despite maintaining an intense belief in the power of blood connection, Bo-hee remains distrustful of the idea of family and uncertain in his own identity. Even his name, which is really just “Boy” like the unnamed protagonist of a young adult novel, bothers him in that is uncomfortably close to slightly rude word, not to mention being somewhat unusual. Nok-yang has an unusual name too, but hers has a lovely, if sad, story behind it about her dad seeing rays of sunshine through the trees on the way home from the hospital and deciding to name her after that, whereas Bo-hee’s seems to be random. Thanks to his quest to track down his dad, Bo-hee finally comes to understand the meaning behind his name and accept himself for himself rather than longing to be just like everyone else.

Like all small children, Bo-hee thought everything that happened in his life was somehow his fault, that his dad left because of something he did or that there was just something wrong with him that his dad couldn’t love. What he realises is that his father’s decision was his father’s and nothing to do with him. It wasn’t his fault that his father left and there is nothing about him that means anyone else in his life is likely to leave without warning. In a roundabout way, looking for his dad helps to rebuild a sense of the family he didn’t think he had, becoming more secure in his relationship with his mother, bonding with Sung-wook and Nam-hee, and remembering that whatever happens he and Nok-yang will always be there for each other.

A Boy and Sungreen was screened as part of the 2019 London Korean Film Festival.

International trailer (English subtitles)

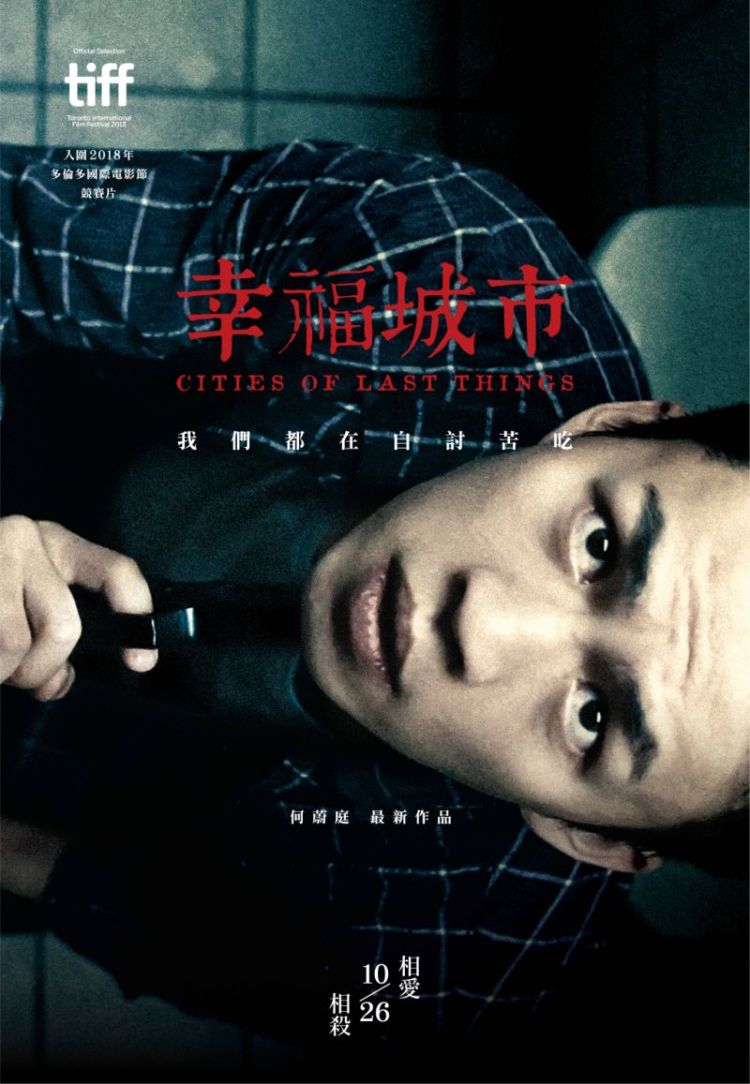

A sense of finality defines the appropriately titled Cities of Last Things (幸福城市, Xìngfú Chéngshì), even as it works itself backwards from the darkness towards the light. Still more ironic, the Chinese title hints at “Happiness City” (neatly subverting Hou Hsiao-hsien’s “City of Sadness”) but that, it seems, is somewhere its hero has never quite felt himself to be. Embittered by a series of abandonments, betrayals, and impossibilities, he grows resentful of the brave new world in which old age has marooned him.

A sense of finality defines the appropriately titled Cities of Last Things (幸福城市, Xìngfú Chéngshì), even as it works itself backwards from the darkness towards the light. Still more ironic, the Chinese title hints at “Happiness City” (neatly subverting Hou Hsiao-hsien’s “City of Sadness”) but that, it seems, is somewhere its hero has never quite felt himself to be. Embittered by a series of abandonments, betrayals, and impossibilities, he grows resentful of the brave new world in which old age has marooned him.