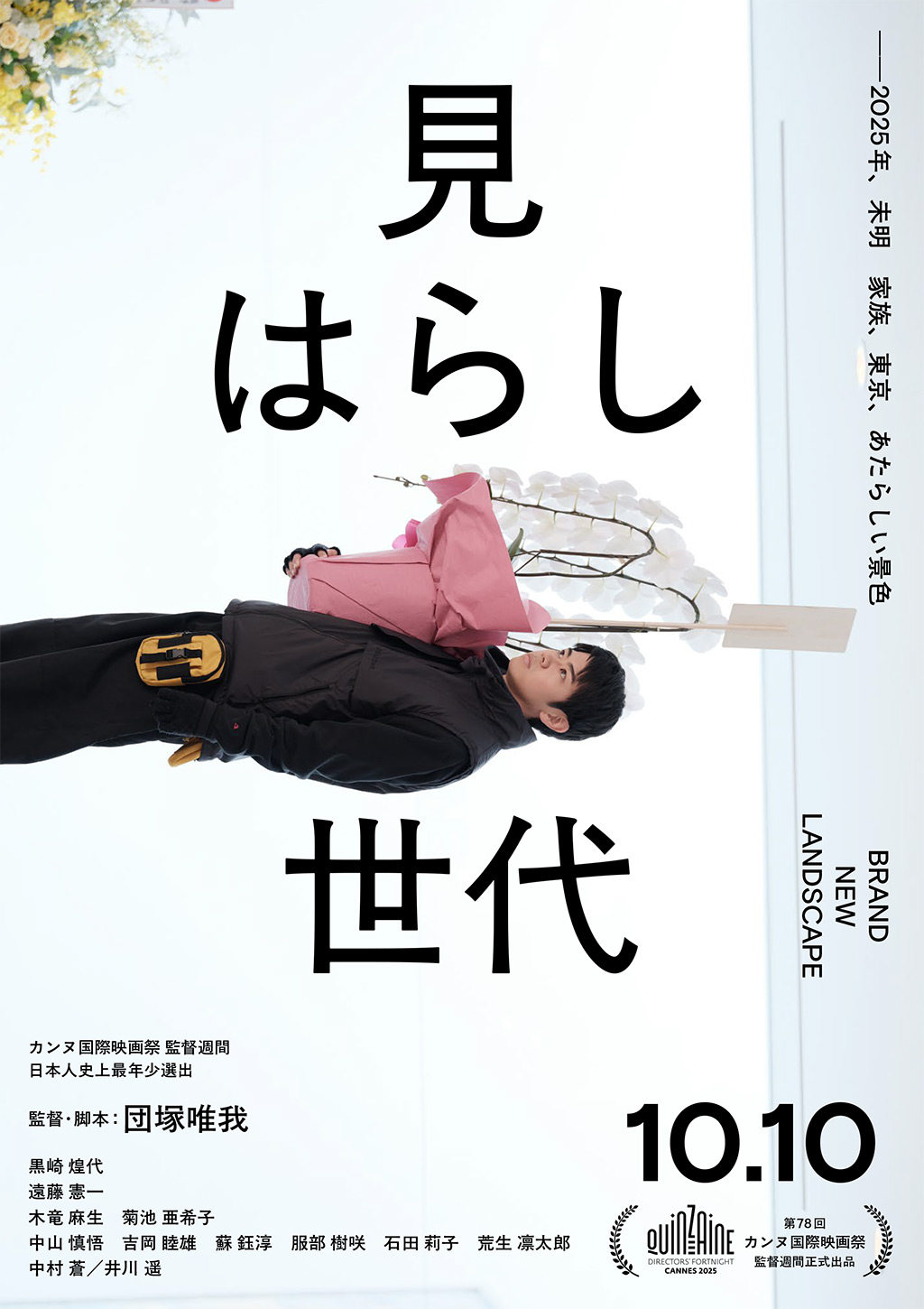

Do we inhabit spaces, or do the spaces inhabit us? Yuiga Danzuka’s autobiographically inspired Brand New Landscape (見はらし世代, Miwarashi Sedai) situates itself in a haunted Tokyo which is forever remaking itself around its inhabitants like a constantly retreating cliff edge that leaves them all rootless and in search of a home that no longer exists. Some long for a return to the past and wander endlessly, while others defiantly refuse to look back and are content to let history eclipse itself in a journey towards an ineffable “new”.

These imprinted spaces come to represent the disintegration of a family torn apart by their shifting foundations. Ten years previously, Ren (Kodai Kurosaki) and Emi’s (Mai Kiryu) mother, Yumi (Haruka Igawa), took her own life during a family holiday after their father Hajime (Kenichi Endo) told her that, despite his promises, he would be returning to Tokyo to pursue a work opportunity. “It’s pointless to go back and forth like this,” he remarks with exasperation, making it clear that he’ll be going no matter what she says. Rather than simply being a workaholic, Hajime is a deeply selfish person who doesn’t much care how other people are affected by the decisions that he makes. He wants this opportunity to prove himself and acts out of a mixture of vanity and a desire for external validation through professional acclaim rather than the love of his family. He claims he’s doing this for them, that the opportunity will provide additional financial security and a better quality of life for his children, but Yumi replies that they don’t need any more money. All she wanted was family time, albeit within this artificial domestic space of a rented holiday villa by the sea.

Three years after their mother’s death, Hajime left the children to chase opportunities abroad and they haven’t seen him in years. Younger son Ren is now working as a floral delivery driver for a company selling expensive moth orchids. It’s on a job that he first learns that Hajime has returned and is holding an exbitiion of his work that includes the controversial Miyashita Park redevelopment project designed to fuse the natural space of the park with a commercial centre the exhibition’s copy describes as a symbol of the “new” Tokyo. It also, however, required the displacement of a number of unhoused people who were living in the park in order to provide space for upscale outlets such as Louis Vuitton and Gucci. When Hajime accepts the opportunity to work on another such project, a young woman on his team voices her concern. She asks him where these unhoused people are supposed to go, but Hajime says it’s not his problem. It’s for the authorities to decide. She asks him if he’s considered the effect taking on such a large project will have on their team when the company is already working beyond its limit, but he gives her all the same excuses he gave Yumi that make it clear he’s not interested in the needs and well-being of his employees just as he wasn’t interested in those of his family. “It’s pointless going back and forth,” he tells her while trying to sound sympathetic but really emphasising that his decision is made and nothing she could say would sway him from his course.

Maybe, to that extent, oldest daughter Emi is much the same in that she’s decided she doesn’t want to see her father and resents Ren’s attempts to force her into doing so. She’s about to move in with her boyfriend and looking ahead towards marriage, but also prone to “low energy” days like her mother and anxious in her relationships, fearful that like that of her parents’ they can only end in failure. Ren, meanwhile, struggles with authority figures like his ridiculous boss who tries to assert dominance by giving him a public telling off about the non-standard colour of his hip pack, and then yells at him that he’s fired only to chase him out of the building throwing punches when Ren calmly replies that shouting only makes him look silly. In the midst of the drama, another young woman states her own intention to quit, politely bowing to everyone except one particular man before walking out the other door towards freedom as if to remind us that there are countlessly other stories going on in this city at the same time.

There’s a moment when Ren is delivery the orchids that he just stands there holding them, like he doesn’t know where to go or what to do. He’s lost within this space and is unable to find his way back within a Tokyo that’s always changing. In an attempt to find some sort of resolution, he drives Emi back to the service station where they had their final meal as a family, only their mother’s chair remains painfully empty. A perpetually falling ceiling light hints at the unreliability of these spaces. It isn’t and can’t ever be the same place it was before and has taken on new meanings for all concerned. Ren stares up at the Miyashita Park development as if caught between admiring his father’s achievement, wondering if it was worth it, and mourning the loss of everything it eclipsed in building over the past with a “new” that will quickly become the “old” and then be rebuilt and replaced. Nevertheless, he has perhaps begun a process of moving on even if for him moving forward lies in looking back.

Brand New Landscape screens as part of this year’s San Diego Asian Film Festival.

Original trailer (no subtitles)