“As long as somebody like you is around, there’s hope for Japan,” an oddly sympathetic prison warden says to the last patriot standing in post-war Osaka. The title of Norifumi Suzuki’s Sonny Chiba vehicle The Killing Machine (少林寺拳法, Shorinji Kempo) maybe somewhat inappropriate or at least potentially misleading as the film is deliberately constructed as a martial arts parable emphasising the spiritual philosophy of self-improvement and compassion that is inextricable from its practice.

To that extent, the hero, Soh Doushin (Shinichi Chiba), is trying to fight his way out of the miasmas of the immediate post-war era. As may be apparent, Soh has taken a Chinese name, though Soh was apparently his along and belonged to a former samurai family whose nobility has been crushed by militarism. As the film opens, however, he’s a Japanese secret service operative in Manchuria blindsided by the news of Japan’s surrender. Soh is it seems a nationalist and a patriot, but a fairly revisionist one who stands up to the abuses of the Japanese army. He later says that he protested the way that the local Chinese population were often treated and he does indeed raise a fist toward an officer who wants to sell a young Japanese woman to a Chinese soldier in return for a guarantee of their safe passage to a boat heading out of the country. The young woman’s mother protests that she is an innocent virgin, a fact that has some later relevance. Soh refuses to let the officers take her, though evidently separated from her later.

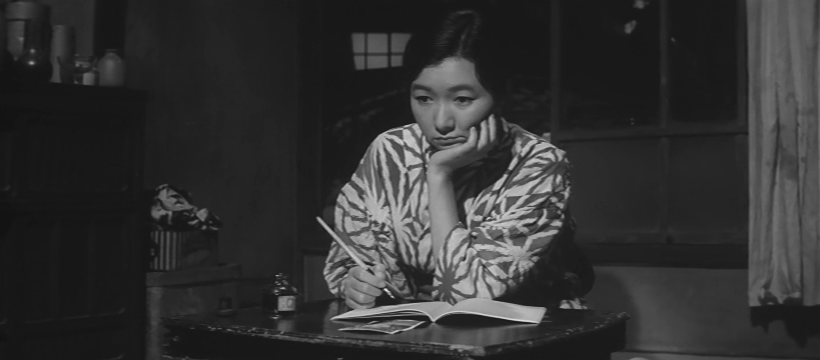

When he meets the young woman again in the bomb-damaged backstreets of Occupation Osaka, she is dressed in Western clothing as opposed to the smart kimono she wore in Manchuria and is about to become a “pan pan” or streetwalking sex worker catering to American servicemen. Of course, Soh can’t let this happen either, but as she later tells him, she was raped by Russian soldiers during the retreat and now feels herself to be despoiled. She never wears kimono again and becomes a kind of symbol for a despoiled nation that Soh is reluctantly forced to accept he cannot save in part because his philosophy, which is still uncomfortably rooted in the philosophy of militarism, only valued strength when it should have valued love. The kind of love that Kiku (Yutaka Nakajima) had for her brother that made her willing to sacrifice herself for his wellbeing.

Even so, Soh is doing his best to issue a course correction by caring for a small group of war orphans and helping them support themselves by running a rice soup stall so they won’t end up becoming dependent on the yakuza or the black market. It’s the yakuza and their increasingly corporatising nature that become Soh’s chief enemies, though standing right behind them are the Occupation Forces. They are, of course, just the biggest gang, as we can see when one of the kids steals a few tins from the gangster’s crate which is marked with text making it clear it came from the mess hall at the American base. The backstreets are full of sleazy soldiers and pan pans or otherwise the starving and dejected, sometimes violent demobbed soldiers filled with despair. It’s these men that Soh wants to buck up, telling them to rediscover their fighting spirit and giving them the opportunity to do so through learning Shaolin martial arts.

Of course there are those who don’t want to learn Chinese kung fu in the midst of their defeat, but what Soh is advocating is something that has a greater spiritual application even than karate can also have. It’s a kind of humanitarian riposte to the futility of the post-war society that might sometimes fail to recognise the depths of the impossibility faced by many in insisting they can be faced by discipline and moral fortitude but at the same time is not really judgemental except toward those who have deliberately abandoned their humanity, such as the trio of goons who rape a school for amusement (the girl is later seen among the students at Soh’s school along with the children from Osaka). The girl’s father reports it to the police, but the police and the gangsters are in cahoots, so nothing gets done. Soh cuts the guy’s bits off so he won’t be doing that again. Strength without justice is violence, he realises. But justice without strength is inability. Strength and love like body and mind should never be separated. The closing shots show an entire mountain covered in white-clad figures practising Shaolin kung fu and joining the humanitarian revolution rather than the cruel and selfish one represented by the gangsters with their red-light districts and black markets. It may be a simplistic solution, but it is in its way satisfying and at least a rejection both of the militarist past and the capitalistic future.

*Norifumi Suzuki’s name is actually “Noribumi” but he has become known as “Norifumi” to English-speaking audiences.

The saga seemed complete with the end of

The saga seemed complete with the end of  If the under seen yet massively influential director Yasuzo Masumura had one recurrent concern throughout his career, passion, and particularly female passion, is the axis around which much of his later work turns. Masumura might have begun with the refreshingly innocent love story

If the under seen yet massively influential director Yasuzo Masumura had one recurrent concern throughout his career, passion, and particularly female passion, is the axis around which much of his later work turns. Masumura might have begun with the refreshingly innocent love story