By 1965, Japan was back on the international map as the host of the last Olympics. The world was opening up, but the gleefully surreal universe of Toho spy movies isn’t convinced that’s an entirely good thing. Jun Fukuda had begun his career at Toho working on more “serious“ fare but throughout the 1960s began to lean towards comedy of the absurd, slapstick variety. 1965’s Ironfinger (100発100中, Hyappatsu Hyakuchu) boasts a script by Kihachi Okamoto – Okamoto might be best remembered for his artier pieces but even these are underpinned by his noticeably surreal sense of humour and Ironfinger is certainly filled with the director’s cheerful sense of cartoonish fun with its colourful smoke bombs, cigarette lighters filled with cyanide gas, and zany mid-air rescues. The English title is, obviously, a James Bond reference (the Japanese title is the relatively more typical “100 shots, 100 Kills”) and the film would also get a 1968 sequel which added the spytastic “Golden Eye” (though it would be given a more salacious title, Booted Babe, Busted Boss, for export). Strangely the unlikely villains this time around are the French as Tokyo finds itself at the centre of an international arms smuggling conspiracy unwittingly uncovered by a “bumbling vacationer”.

By 1965, Japan was back on the international map as the host of the last Olympics. The world was opening up, but the gleefully surreal universe of Toho spy movies isn’t convinced that’s an entirely good thing. Jun Fukuda had begun his career at Toho working on more “serious“ fare but throughout the 1960s began to lean towards comedy of the absurd, slapstick variety. 1965’s Ironfinger (100発100中, Hyappatsu Hyakuchu) boasts a script by Kihachi Okamoto – Okamoto might be best remembered for his artier pieces but even these are underpinned by his noticeably surreal sense of humour and Ironfinger is certainly filled with the director’s cheerful sense of cartoonish fun with its colourful smoke bombs, cigarette lighters filled with cyanide gas, and zany mid-air rescues. The English title is, obviously, a James Bond reference (the Japanese title is the relatively more typical “100 shots, 100 Kills”) and the film would also get a 1968 sequel which added the spytastic “Golden Eye” (though it would be given a more salacious title, Booted Babe, Busted Boss, for export). Strangely the unlikely villains this time around are the French as Tokyo finds itself at the centre of an international arms smuggling conspiracy unwittingly uncovered by a “bumbling vacationer”.

We first meet our hero as he’s writing a postcard to his mum in which he details his excitement in thinking that he’s made a friend of the nice Japanese man in the next seat seeing as he’s finally stopped ignoring him. When they land in Hong Kong, our guy keeps shadowing his “friend” until he decides to ask him about “Le Bois” to which his “friend” seems surprised but is gunned down by bike riding assassins before he can answer though he manages to get out the word “Tokyo” before breathing his last. Picking up his friend’s passport and swanky hat, our guy becomes “Andrew Hoshino” (Akira Takarada) – a “third generation Japanese Frenchman” and “possibly” a member of Interpol.

The bumbling “Andy”, who can’t stop talking about his mother and is very particular about his hat (for reasons which will become clear), is obviously not all he seems. Despite his penchant for pratfalls and cheeky dialogue, he also seems to be a crack shot with a pistol and have an ability to talk himself out of almost any situation – at least with the aid of his various spy gadgets including his beloved cigarette lighter and a knife concealed in his wristwatch for cutting himself free should he get tied up. Andy “said” he was just here on holiday, but are all those postcards really for his dear old mum waiting for him in Paris or could they have another purpose? Why is he so keen on finding out about “Le Bois” and why does he always seem to end up at the centre of the action?

These are all questions which occur to one of his early antagonists – Yumi (Mie Hama), the ace explosives expert who often feels under-appreciated in the otherwise all male Akatsuki gang. Apprehending Andy, Yumi originally falls for his bumbling charm only to quickly see through his act and realise she might be better hedging her bets with him – hence she finally teams up with Andy and straight laced streetcop Tezuka (Ichiro Arishima) who’s been trying to keep a lid on the growing gang violence between the Aonuma who now run the town and the Akatsuki who want to regain control. Andy doesn’t much care about sides in a silly territorial dispute, but it might all prove helpful in his overall mission which is, it turns out, very much in keeping both with that of the gang-affiliated Yumi and law enforcement officer Tezuka.

There isn’t much substance in Ironfinger, but then there isn’t particularly intended to be. There is however a mild degree of international anxiety as our heroes become, in a sense, corrupted by French sophistication whilst “relying” on “Interpol” to solve all their problems (“Interpol” is frequent presence in Toho’s ‘60s spoofs providing a somewhat distant frontline defence against international spy conspiracies). Fukuda keeps things moving to mask the relative absence of plot as the guys get themselves into ever more extreme scrapes before facing certain death on a mysterious island only to save themselves through a series of silly boys own schemes to outwit their captors. Perhaps not as much fun or not quite as interesting as some of Toho’s other humorous ‘60s fare, Ironfinger is nevertheless a good old fashioned espionage comedy filled with zany humour and a cartoonish sense of the absurd.

Akira Takarada shows off his French

1969. Man lands on the moon, the cold war is in full swing, and Star Trek is cancelled prompting a mass write-in campaign from devoted sci-fi enthusiasts across America. The tide was also turning politically as the aforementioned TV series’ utopianism came to gain ground among liberal thinking people who rose up to oppose war, racial discrimination and sexism. It was in this year that Godzilla creators Ishiro Honda and Eiji Tsuburaya brought their talents to America with a very contemporary take on science fiction in Latitude Zero (緯度0大作戦, Ido Zero Daisakusen). Starring Hollywood legend Joseph Cotten, Latitude Zero gives Jules Verne a new look for the ‘60s filled with solid gold hotpants and bulletproof spray tan.

1969. Man lands on the moon, the cold war is in full swing, and Star Trek is cancelled prompting a mass write-in campaign from devoted sci-fi enthusiasts across America. The tide was also turning politically as the aforementioned TV series’ utopianism came to gain ground among liberal thinking people who rose up to oppose war, racial discrimination and sexism. It was in this year that Godzilla creators Ishiro Honda and Eiji Tsuburaya brought their talents to America with a very contemporary take on science fiction in Latitude Zero (緯度0大作戦, Ido Zero Daisakusen). Starring Hollywood legend Joseph Cotten, Latitude Zero gives Jules Verne a new look for the ‘60s filled with solid gold hotpants and bulletproof spray tan. As Japan’s society ages, the lives of older people have begun to take on an added dimension. Rather than being relegated to the roles of kindly grandmas or grumpy grandpas, cinema has finally woken up to the fact that older people are still people with their own stories to tell even if they haven’t traditionally fitted established cinematic genres. Of course, some of this is down to the power of the grey pound rather than an altruistic desire for inclusive storytelling but if the runaway box office success of A Sparkle of Life (燦燦 さんさん, Sansan) is anything to go by, there may be more of these kinds of stories in the pipeline.

As Japan’s society ages, the lives of older people have begun to take on an added dimension. Rather than being relegated to the roles of kindly grandmas or grumpy grandpas, cinema has finally woken up to the fact that older people are still people with their own stories to tell even if they haven’t traditionally fitted established cinematic genres. Of course, some of this is down to the power of the grey pound rather than an altruistic desire for inclusive storytelling but if the runaway box office success of A Sparkle of Life (燦燦 さんさん, Sansan) is anything to go by, there may be more of these kinds of stories in the pipeline. The Ainu have not been a frequent feature of Japanese filmmaking though they have made sporadic appearances. Adapted from a novel by Nobuo Ishimori, Whistling in Kotan (コタンの口笛, Kotan no Kuchibue, AKA Whistle in My Heart) provides ample material for the generally bleak Naruse who manages to mine its melodramatic set up for all of its heartrending tragedy. Rather than his usual female focus, Naruse tells the story of two resilient Ainu siblings facing not only social discrimination and mistreatment but also a series of personal misfortunes.

The Ainu have not been a frequent feature of Japanese filmmaking though they have made sporadic appearances. Adapted from a novel by Nobuo Ishimori, Whistling in Kotan (コタンの口笛, Kotan no Kuchibue, AKA Whistle in My Heart) provides ample material for the generally bleak Naruse who manages to mine its melodramatic set up for all of its heartrending tragedy. Rather than his usual female focus, Naruse tells the story of two resilient Ainu siblings facing not only social discrimination and mistreatment but also a series of personal misfortunes. Mikio Naruse made the lives of everyday women the central focus of his entire body of work but his 1963 film, A Woman’s Story (女の歴史, Onna no Rekishi), proves one of his less subtle attempts to chart the trials and tribulations of post-war generation. Told largely through extended flashbacks and voice over from Naruse’s frequent leading actress, Hideko Takamine, the film paints a bleak vision of the endless suffering inherent in being a woman at this point in history but does at least offer a glimmer of hope and understanding as the curtains falls.

Mikio Naruse made the lives of everyday women the central focus of his entire body of work but his 1963 film, A Woman’s Story (女の歴史, Onna no Rekishi), proves one of his less subtle attempts to chart the trials and tribulations of post-war generation. Told largely through extended flashbacks and voice over from Naruse’s frequent leading actress, Hideko Takamine, the film paints a bleak vision of the endless suffering inherent in being a woman at this point in history but does at least offer a glimmer of hope and understanding as the curtains falls. Hibari, Chiemi and Izumi reunite in 1964 for another tale of musical comedy and romantic turmoil in Sannin Yoreba (三人よれば). Beginning as teenagers in

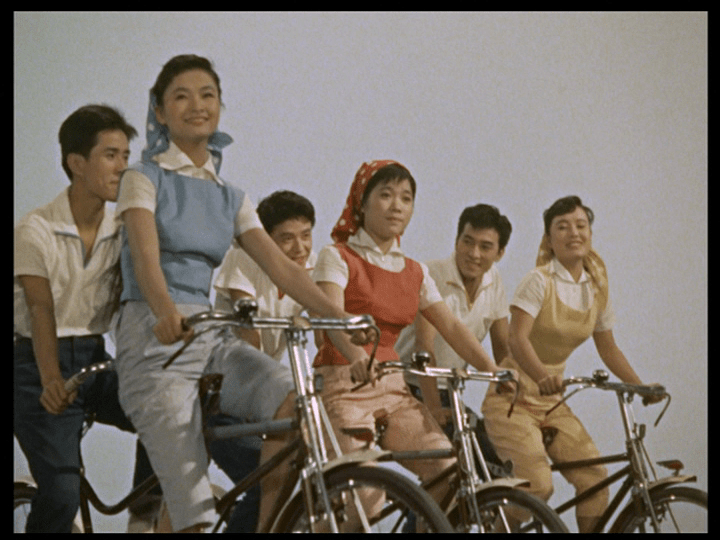

Hibari, Chiemi and Izumi reunite in 1964 for another tale of musical comedy and romantic turmoil in Sannin Yoreba (三人よれば). Beginning as teenagers in  The Sannin Musume girls are growing up by the time we reach 1957’s On Wings of Love (大当り三色娘, Ooatari Sanshoku Musume). In fact, they each turned 20 this year (which is the age you legally become an adult in Japan), so it’s out with the school girl stuff and in with more grown up concerns, or more specifically marriage. Wings of Love is the third film to star the three Japanese singing stars Hibari Misora, Chiemi Eri, and Izumi Yukimura who come together to form the early idol combo supergroup Sannin Musume. Once again modelled on the classic Hollywood musical, On Wings of Love is the very first Tohoscope film giving the girls even more screen to fill with their by now familiar cute and colourful antics.

The Sannin Musume girls are growing up by the time we reach 1957’s On Wings of Love (大当り三色娘, Ooatari Sanshoku Musume). In fact, they each turned 20 this year (which is the age you legally become an adult in Japan), so it’s out with the school girl stuff and in with more grown up concerns, or more specifically marriage. Wings of Love is the third film to star the three Japanese singing stars Hibari Misora, Chiemi Eri, and Izumi Yukimura who come together to form the early idol combo supergroup Sannin Musume. Once again modelled on the classic Hollywood musical, On Wings of Love is the very first Tohoscope film giving the girls even more screen to fill with their by now familiar cute and colourful antics. Romantic Daughters (ロマンス娘, Romance Musume) is the second big screen outing for the singing star combo known as “sannin musume”. A year on from

Romantic Daughters (ロマンス娘, Romance Musume) is the second big screen outing for the singing star combo known as “sannin musume”. A year on from