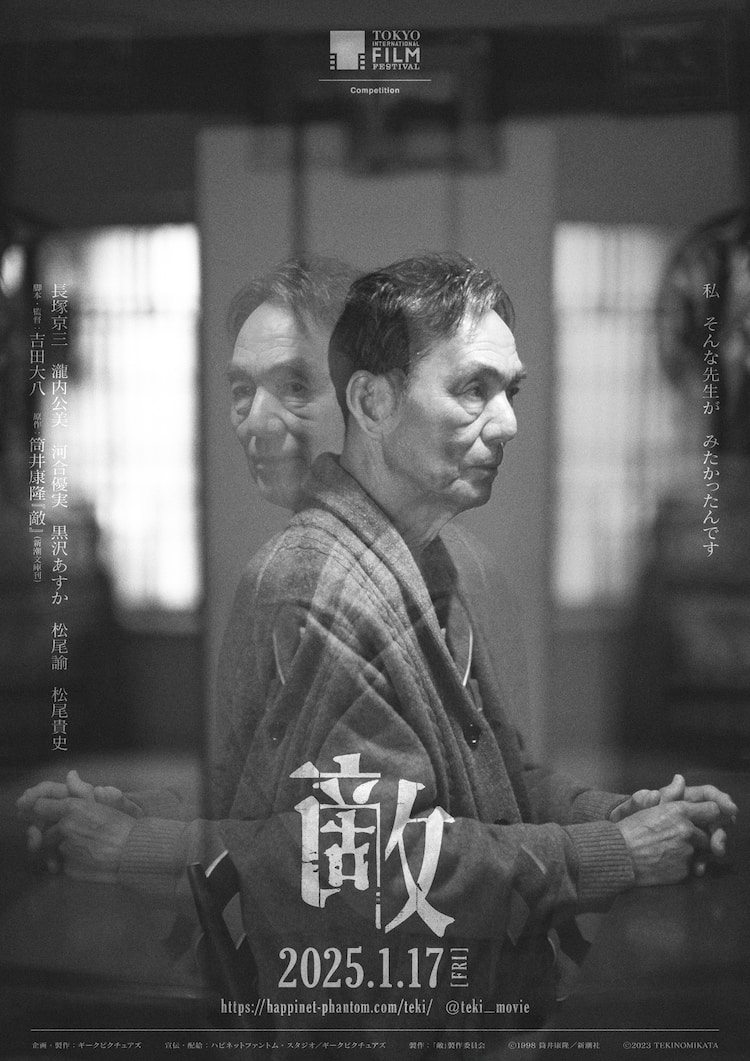

“So, reality or literature, which is more important?” an unexpected guest asks a retired professor in Daihachi Yoshida’s Teki Cometh (敵, Teki). Adapted from the novel by Yasutaka Tsutsui, the film is not exactly about encroaching dementia but rather the gradual embrace of fantasy as the hero finds himself inhabiting the shifting realities of age in which his carefully curated persona of the refined professor begins to crack under the weight of its impending end.

Then again, objective “reality” is clearly a strain for Gisuke Watanabe (Kyozo Nagatsuka). It’s probably not a coincidence that Gisuke shares his surname with the hero of Kurosawa’s Ikiru as he too begins to ponder the meaning of his life along with the apparently meaninglessness of his twilight years. He reveals to his friend that he’s well aware his pension won’t cover his expenses for the rest of his projected lifespan and that he’s already calculated what he calls “X-Day” which will be the day the money (and implicitly his life) will simply run out. This day is continually postponed as Gisuke acquires extra money through giving lectures on French literature or writing articles for magazines, but the early part of the film at least is all about money and its relative values. Gisuke says that he does not really contemplate the price of the newspaper because the newspaper is something he wants so he simply buys it while taking out half the amount he’d usually charge for a lecture from an ATM machine. His friend advises him to drop his fees and get more work, but Gisuke explains that his 100,000 yen boundary is carefully maintained as a kind of bulwark against a sense of obsolescence as in he thinks they’ll keep haggling him down until he’s grateful just to get anything at all.

But obsolescence is clearly something he already feels given that interest in his chosen field has already declined and perhaps there no longer is much of an audience for his views on Racine and the development of the French language. Like the professor at the centre of Kurosawa’s Madadayo, Gisuke is surrounded by former students most of whom do not work in fields related to their studies but continue to hold him up as great scholar and influential figure in their lives. Yet as the film goes on and realities begin to blur, we might begin to wonder if any of these visitors are actually real or merely spectres leaking out from Gisuke’s fracturing memory to express his own anxieties about past and present. Former student Yasuko (Kumi Takiuchi) appears to be flirting with him, but on the other perhaps she’s merely reflecting the buried desires for which he continues to feel guilt and shame. He recalls times in which they attended the theatre together and then went for meals and drinks as if they were quasi-paternal or at least platonic, but Yasuko asks him if it wasn’t sexual harassment while at the same time directly stating that the desire is mutual (and there’s 15 minutes left before her train leaves).

From this point on, Gisuke begins having strange dreams perhaps inspired by weird messages he’s receiving about an “enemy” that’s “coming from the north”. The “north” in a Japanese context would most likely be Russia and the messages reflecting a fear of invasion but also perhaps implying that in Gisuke’s case, the enemy lies within and it’s his own brain that is attacking itself. The illicit desires that he hints at to another former student while discussing his brief foray into and eventual boredom with voyeurism begin to come to the fore in his surreal dreams including one where he is subjected to a colonoscopy that is heavily influenced by BDSM imagery. His surprise visitor asks him if he remembers the war and Gisuke says that he’s told he experienced it in the womb, implying that he carries a degree of trauma from a time before he was even born. The ghost of the grandfather he never met haunts his well-appointed Japanese-style home that speaks of his traditionalism, while Gisuke himself tenderly takes out his late wife’s old coat and deeply breathes in her scent before hanging the coat up in his office so that it too floats like a ghost.

Yoshida structures the film through a series of vignettes ordered by season, yet there’s nothing necessarily to say that the seasons are consecutive or occur within the same year. Time is becoming abstract to Gisuke, even as he’s pursued by his invisible “enemy” that attacks his respectable facade and the very image of himself as he too embraces fantasy as a means of liberation from an otherwise monotonous if also serene life of awaiting the inevitable. The monochrome photography and static composition add to the air of deadpan humour in Gisuke’s increasingly surreal world. Teki cometh for us all, but in the end teki is us and we are teki. Our own fears, regrets, and insecurities will indeed return to torment us and show us who we are. Likely as not will not like what we see.

Teki Cometh screens in Chicago 11th April as part of the 19th edition of Asian Pop-Up Cinema.

Original trailer (English subtitles)