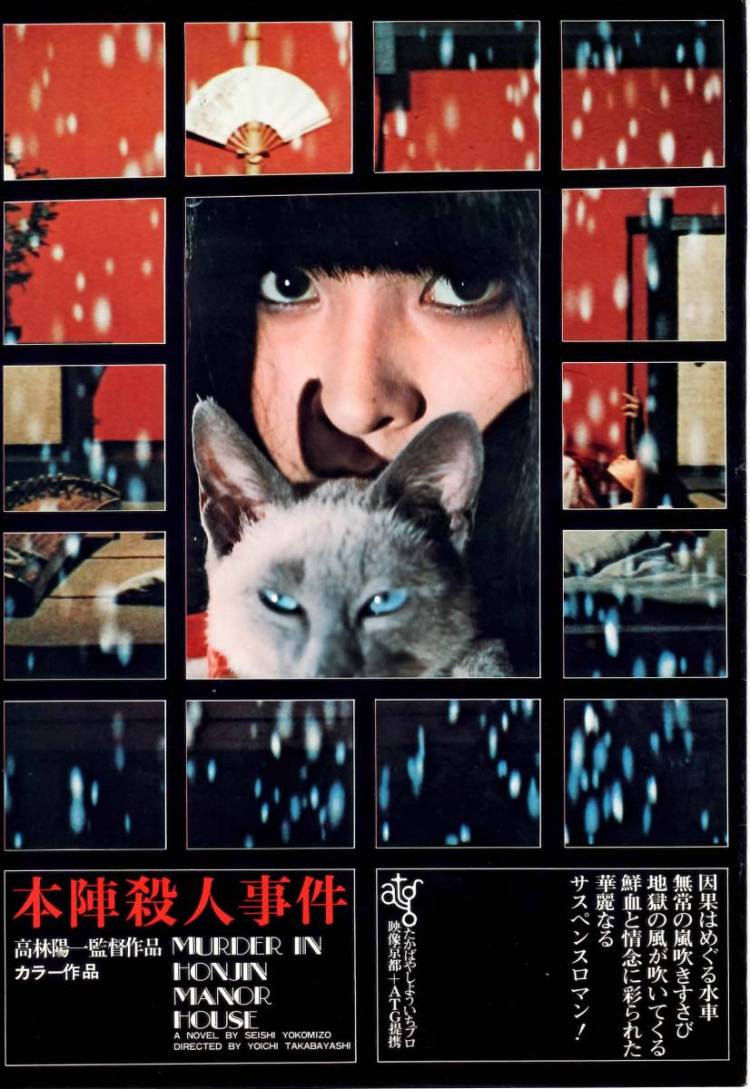

Kousuke Kindaichi is one of the best known detectives of Japanese literature. There are 77 books in the Kindaichi series which has spawned numerous cinematic adaptations as well as a popular manga and anime spin-off starring the grandson of the original sleuth. Sadly only one of Seishi Yokomizo’s novels has been translated into English (The Inugami Clan which has the distinction of having been filmed not once but twice by Kon Ichikawa), but many Japanese mystery lovers have ranked his debut, The Murder in the Honjin, as one of the best locked room mysteries ever written. Starring Akira Nakao as the eccentric detective, Yoichi Takabayashi’s Death at an Old Mansion (本陣殺人事件, Honjin Satsujin Jiken) was the first of three films he’d make for The Art Theatre Guild of Japan and updates the 1937 setting of Yokomizu’s novel to the contemporary 1970s.

Kousuke Kindaichi is one of the best known detectives of Japanese literature. There are 77 books in the Kindaichi series which has spawned numerous cinematic adaptations as well as a popular manga and anime spin-off starring the grandson of the original sleuth. Sadly only one of Seishi Yokomizo’s novels has been translated into English (The Inugami Clan which has the distinction of having been filmed not once but twice by Kon Ichikawa), but many Japanese mystery lovers have ranked his debut, The Murder in the Honjin, as one of the best locked room mysteries ever written. Starring Akira Nakao as the eccentric detective, Yoichi Takabayashi’s Death at an Old Mansion (本陣殺人事件, Honjin Satsujin Jiken) was the first of three films he’d make for The Art Theatre Guild of Japan and updates the 1937 setting of Yokomizu’s novel to the contemporary 1970s.

Beginning at the end, Kindaichi (Akira Nakao) arrives at a country mansion with a sense of foreboding which borne out when he realises that the young lady he’s come to see, Suzu (Junko Takazawa), has died and he’s arrived just in time to witness her funeral. It’s been a year since he first met her, though he did so under less than ideal circumstances. As it happened, Suzu’s older brother, Kenzo (Takahiro Tamura), was married to a young woman of his own choosing, Katsuko (Yuki Mizuhara), despite strong familial opposition. On the night of their wedding, the couple were brutally murdered inside a private annex to the main building. The doors were firmly locked from the inside and there was no murder weapon on site. The only clue was bloody three fingered handprint made by someone wearing the “tsume” or picks used for playing the koto. Kindaichi, already a well known private detective, was summoned to investigate because of a personal connection to Katsuko’s uncle, Ginzo (Kunio Kaga).

The original novel was published in 1946 and it has to be said, some of its themes make more sense in the pre-war 1937 setting than they do for the comparatively more liberal one of 1975 though such small minded attitudes are hardly uncommon even in the world today. The Ichiyanagi family live on a large family estate (apparently not the “Honjin” – a resting place for imperial retinues in the Edo era, of the title but the ancestral association remains) and enjoy a degree of social standing as well as the privilege of wealth in the small rural town. Katsuko, by contrast, is from a “lowly” family of well-to-do farmers – mere peasantry to the Ichiyanagis, many of whom believe Kenzo is making a huge and embarrassing mistake in his choice of wife. Kenzo, a middle-aged scholar, has shocked them all with his sudden determination to marry, not to mention his determination to break with family protocol and marry beneath him.

Japanese mysteries are much less concerned with motive than their Western counterparts, but class conflict is definitely offered as a possible reason for murder. Other clues have more menacing dimensions such as the repeated mentions of a scary looking three fingered man who apparently delivered a threatening letter to the mansion on the night of the murder, and Suzu’s constant questions about her recently deceased cat who liked to listen to her play the koto. Suzu is 17 but has some kind of learning difficulties and is arrested in a childlike state of innocence which leads her to utter simple yet profound words of wisdom whilst also believing that her recently deceased cat, Tama, is some kind of god. Suzu’s “innocence” is contrasted with her brother’s coldhearted rigidity in which he’s described as a sanctimonious snob who believes himself above regular folk and treats his servants with contempt. This same rigidity in fact aligns him with his sister as both share an “atypical” way of thought and behaviour. Kenzo’s unexpected romance turns out not to be middle-aged lust for domination but an innocent first love arriving at 40 with all the pain and complication of adolescence.

Kindaichi arrives to solve the crime and makes an instant partner of the police inspector in charge who’s glad to have such esteemed help on such a difficult case. Putting two and two together, Kindaichi soon comes up with a few ideas after rubbing up against a mystery novel obsessed suspect and numerous red herrings. Once again coincidence plays a huge role, but the business of the murder is certainly elaborate given the pettiness of the reasoning behind it. Takabayashi never plays down the typically generic elements of this classic mystery, but adds to them with eerie, occasionally psychedelic camera work, shifting to sepia for imagined reconstructions and making use of repeated motifs from the fire-like imagery of the water wheel to a shattered photo of Kenzo shot through the eye. Strangely framed in red and gold the murder takes on a theatrical association that’s perfectly in keeping with its well choreographed genesis, and all the more chilling because of it. A satisfying locked room mystery, Death at an Old Mansion is also a tragedy of out dated ideals equated with a kind of innocence and purity, of those who couldn’t allow their dreams to be sullied or their name besmirched. Perhaps not so different from the world of 1937 after all.

Original trailer (no subtitles)

The family drama went through something of a transformation at the beginning of the 1980s. Gone are the picturesque, sometimes melancholy evocations of the transience of family life, these families are fake, dysfunctional, or unreliable even if trying their best. Morita’s

The family drama went through something of a transformation at the beginning of the 1980s. Gone are the picturesque, sometimes melancholy evocations of the transience of family life, these families are fake, dysfunctional, or unreliable even if trying their best. Morita’s  Yukio Mishima’s Temple of the Golden Pavilion has become one of his most representative works and seems to be one of those texts endlessly reinterpreted by each new generation. Previously adapted for the screen by Kon Ichikawa under the title of

Yukio Mishima’s Temple of the Golden Pavilion has become one of his most representative works and seems to be one of those texts endlessly reinterpreted by each new generation. Previously adapted for the screen by Kon Ichikawa under the title of  Every story is a ghost story in a sense. In every photograph there’s a presence which cannot be seen but is always felt. The filmmaker is a phantom and an enigma, but can we understand the spirit from what we see? Whose viewpoint are seeing, and can we ever separate that subjective vision from the one we create for ourselves within our own minds? The Man Who Left his Will on Film (東京戰争戦後秘話, Tokyo Senso Sengo Hiwa) is an oblique examination of identity but more specifically how that identity is repurposed through cinema as cinema is repurposed as a political weapon.

Every story is a ghost story in a sense. In every photograph there’s a presence which cannot be seen but is always felt. The filmmaker is a phantom and an enigma, but can we understand the spirit from what we see? Whose viewpoint are seeing, and can we ever separate that subjective vision from the one we create for ourselves within our own minds? The Man Who Left his Will on Film (東京戰争戦後秘話, Tokyo Senso Sengo Hiwa) is an oblique examination of identity but more specifically how that identity is repurposed through cinema as cinema is repurposed as a political weapon. Sparkling seas sound like hopeful things, especially if you’re a majestic seagull flying far above, bathed in perpetual sunshine. But then, perhaps the water below is shining with the shards of broken hopes which float on its surface, is its beauty treacherous or in earnest? So asks the singer of the title song which recurs throughout the film as if to undercut even its brief moments of happiness. There is precious little joy to be found in the lives of the two protagonists of Oh Seagull, Have You Seen the Sparkling Ocean? : An Encounter (鴎よ、きらめく海を見たか めぐり逢い, Kamome yo, Kirameku Umi wo Mitaka: Meguriai), only pain and confusion as they try to rebuild their ruined lives in an uncaring city.

Sparkling seas sound like hopeful things, especially if you’re a majestic seagull flying far above, bathed in perpetual sunshine. But then, perhaps the water below is shining with the shards of broken hopes which float on its surface, is its beauty treacherous or in earnest? So asks the singer of the title song which recurs throughout the film as if to undercut even its brief moments of happiness. There is precious little joy to be found in the lives of the two protagonists of Oh Seagull, Have You Seen the Sparkling Ocean? : An Encounter (鴎よ、きらめく海を見たか めぐり逢い, Kamome yo, Kirameku Umi wo Mitaka: Meguriai), only pain and confusion as they try to rebuild their ruined lives in an uncaring city. 1973 is the year the ninkyo eiga died. Or that is to say, staggered off into an alleyway clutching its stomach and vowing revenge whilst simultaneously seeking forgiveness from its beloved oyabun after being cruelly betrayed by the changing times! You might think it was Kinji Fukasaku who turned traitor and hammered the final nail into the coffin of Toei’s most popular genre, but Sadao Nakajima helped ram it home with the riotous explosion of proto-punk youth movie and jitsuroku-style naturalistic look at the pettiness and squalor inherent in the yakuza life – Aesthetics of a Bullet (鉄砲玉の美学, Teppodama no Bigaku). This tale of a small time loser playing the supercool big shot with no clue that he’s a sacrificial pawn in a much larger power struggle is one that has universal resonance despite the unpleasantness of its “hero”.

1973 is the year the ninkyo eiga died. Or that is to say, staggered off into an alleyway clutching its stomach and vowing revenge whilst simultaneously seeking forgiveness from its beloved oyabun after being cruelly betrayed by the changing times! You might think it was Kinji Fukasaku who turned traitor and hammered the final nail into the coffin of Toei’s most popular genre, but Sadao Nakajima helped ram it home with the riotous explosion of proto-punk youth movie and jitsuroku-style naturalistic look at the pettiness and squalor inherent in the yakuza life – Aesthetics of a Bullet (鉄砲玉の美学, Teppodama no Bigaku). This tale of a small time loser playing the supercool big shot with no clue that he’s a sacrificial pawn in a much larger power struggle is one that has universal resonance despite the unpleasantness of its “hero”. If the under seen yet massively influential director Yasuzo Masumura had one recurrent concern throughout his career, passion, and particularly female passion, is the axis around which much of his later work turns. Masumura might have begun with the refreshingly innocent love story

If the under seen yet massively influential director Yasuzo Masumura had one recurrent concern throughout his career, passion, and particularly female passion, is the axis around which much of his later work turns. Masumura might have begun with the refreshingly innocent love story  Koichi Goto’s Art Theatre Guild adaptation of Kenji Maruyama’s 1968 novel At Noon (正午なり, Mahiru Nari) begins with a young man on a train. Forlornly looking out of the window, he remains aboard until reaching his rural hometown where he makes a late entry to his parents’ house and is greeted a little less than warmly by his mother. The boy, Tadao, refuses to say why he’s left the big city so abruptly to return to the beautiful, if dull, rural backwater where he grew up.

Koichi Goto’s Art Theatre Guild adaptation of Kenji Maruyama’s 1968 novel At Noon (正午なり, Mahiru Nari) begins with a young man on a train. Forlornly looking out of the window, he remains aboard until reaching his rural hometown where he makes a late entry to his parents’ house and is greeted a little less than warmly by his mother. The boy, Tadao, refuses to say why he’s left the big city so abruptly to return to the beautiful, if dull, rural backwater where he grew up. Nobuhiko Obayashi might be most closely associated with his debut, Hausu, which takes the form of a surreal, totally psychedelic haunted house movie, but in many ways his first feature is not particularly indicative of the rest of Obayashi’s output. 1984’s The Deserted City (AKA Haishi, 廃市), is a much better reflection of the director’s most prominent preoccupations as it once again sees the protagonist taking a journey of memory back to a distant youth which is both forgotten in name yet ever present like an anonymous ghost haunting the narrator with long held regrets and recriminations.

Nobuhiko Obayashi might be most closely associated with his debut, Hausu, which takes the form of a surreal, totally psychedelic haunted house movie, but in many ways his first feature is not particularly indicative of the rest of Obayashi’s output. 1984’s The Deserted City (AKA Haishi, 廃市), is a much better reflection of the director’s most prominent preoccupations as it once again sees the protagonist taking a journey of memory back to a distant youth which is both forgotten in name yet ever present like an anonymous ghost haunting the narrator with long held regrets and recriminations.