Hiroshi Shimizu takes another relaxing sojourn in 1938’s The Masseurs and a Woman (按摩と女, Anma to Onna), this time in a small mountain resort populated by runaways and bullish student hikers. Once again Shimizu follows an atypical narrative structure which begins with the two blind masseurs of the title and the elegant lady from Tokyo but quickly broadens out to investigate the transient hotel environment with even a little crime based intrigue added to the mix.

Hiroshi Shimizu takes another relaxing sojourn in 1938’s The Masseurs and a Woman (按摩と女, Anma to Onna), this time in a small mountain resort populated by runaways and bullish student hikers. Once again Shimizu follows an atypical narrative structure which begins with the two blind masseurs of the title and the elegant lady from Tokyo but quickly broadens out to investigate the transient hotel environment with even a little crime based intrigue added to the mix.

We arrive at the resort town at the same time as the masseurs themselves who’ve walked all the way passing the time playing games with each other over who can guess how many children are in a group travelling the same way or counting how many people they manage to overtake on the road. Comically, their efforts to pass a group of students actually frighten them a little bit so they take off at speed meaning Fuku and Toku miss their daily target.

As well as the group of male students and another group of female ones, the town is also host to a mysterious and beautiful woman from Tokyo who seems both a little sad and a little scared with a tendency to overreact to small sounds and unusual situations. The other main group is a little boy and his uncle with whom he seems to have something of a troubled relationship.

Toku becomes fascinated with Michiho, the mysterious woman from Tokyo, whom he recognises because of her distinctive perfume. Though he is blind, he “watches” her – sensing where she goes and reading her emotional state. He seems to realise there’s very little possibility that she will return his interest, though he allows her to play on the obvious feelings he has for her, and the pair strike up a melancholic friendship. However, Michiho is only interested in making a play for the good looking uncle of the little boy who she has also befriended but the boy eventually goes cold on her, feeling a little rejected because she spends so long talking to his uncle. The two neglected guys, Toku and the boy, form their own kind of friendship as the blind masseur is the only person who is willing to have some fun with him in this slightly less than child friendly resort in which he’s unspeakably bored.

This being a holiday town, it’s a place that only exists for a small amount of time before sinking back into the mists like Brigadoon when the season ends. All things are transient here and everyone is just passing through. The friends you make are just for now and this brief respite from everyday life will fade from the memory like a pleasant dream. Toku ought to know this as he spends his life in such places, providing additional relief for the weary traveller, yet he still has a yearning to connect which is only exacerbated by the feeling that his blindness cuts him off from everyday society.

When a spate of bath house thefts occur and it turns out Michiho has been seen at each of the crime scenes, Toku comes to the obvious conclusion even though his feelings make him reluctant to suspect her. He tries to help Michiho evade punishment for what he believes are her crimes only to find out a very different sort of truth that sees her eventually decide to continue her journey onward to an uncertain future (though at least one that is 100% of her own devising).

Again, Shimizu opts for a lot of location shooting emphasising the beauty of the scenery and the tranquility of the atmosphere. Mostly he sticks to static camera shots, aside from one lengthly tracking sequence and the hand held finale walking after a departing cart, but when he tries to show us the vision of a blind man it’s a striking moment – a whirling chaos where we too can almost smell the elusive perfume of a woman we know is “beautiful” though we cannot see her, and also know is deliberately toying with us. A melancholy look at the transience of human relationships and the impossibility of true connection, The Masseurs and a Woman is a genre melding tragicomedy filled with innovative directorial flourishes that are once again far in advance of their time.

The Masseurs and a Woman is the third of four films in Criterion’s Eclipse Series 15: Travels with Hiroshi Shimizu box set.

This is the only video clip I can find but it’s not subtitled and it has quite a long speech about Hiroshi Shimizu’s career at the beginning so skip to 2:17 for the film itself:

Bus trips might be much less painful if only the drivers were all as kind as Mr. Thank You and the passengers as generous of spirit as the put upon rural folk travelling to the big city in Hiroshi Shimizu’s 1936 road trip (有りがとうさん, Arigatou-san). Set in depression era Japan and inspired by a story by Yasunari Kawabata, Mr. Thank You has its share of sorrows but like its cast of down to earth country folk, smiles broadly even through the bleakest of circumstances.

Bus trips might be much less painful if only the drivers were all as kind as Mr. Thank You and the passengers as generous of spirit as the put upon rural folk travelling to the big city in Hiroshi Shimizu’s 1936 road trip (有りがとうさん, Arigatou-san). Set in depression era Japan and inspired by a story by Yasunari Kawabata, Mr. Thank You has its share of sorrows but like its cast of down to earth country folk, smiles broadly even through the bleakest of circumstances. Hiroshi Shimizu made over 160 films during his relatively short career but though many of them are hugely influential critically acclaimed movies, his name has never quite reached the levels of international renown acheived by his contemporaries Ozu, Naruse, or Mizoguchi. Early silent effort Japanese Girls at the Harbor (港の日本娘, Minato no Nihon Musume) displays his trademark interest in the lives of everyday people but also demonstrates a directing style and international interest that were each way ahead of their time.

Hiroshi Shimizu made over 160 films during his relatively short career but though many of them are hugely influential critically acclaimed movies, his name has never quite reached the levels of international renown acheived by his contemporaries Ozu, Naruse, or Mizoguchi. Early silent effort Japanese Girls at the Harbor (港の日本娘, Minato no Nihon Musume) displays his trademark interest in the lives of everyday people but also demonstrates a directing style and international interest that were each way ahead of their time. Feelings can creep up just like that, to quote another movie. Like Wong Kar-Wai’s In the Mood for Love, Temptation (誘惑, Yuwaku) also echoes Lean’s Brief Encounter with its strains of accidental romance between unavailable people even if only one of the pair is already married. However, this time there’s much less deliberate moralising though the environment itself is a fertile breeding ground for the judgemental.

Feelings can creep up just like that, to quote another movie. Like Wong Kar-Wai’s In the Mood for Love, Temptation (誘惑, Yuwaku) also echoes Lean’s Brief Encounter with its strains of accidental romance between unavailable people even if only one of the pair is already married. However, this time there’s much less deliberate moralising though the environment itself is a fertile breeding ground for the judgemental.

Little Sayuri has had it pretty tough up to now growing up in an orphanage run by Catholic nuns, but her long lost father has finally managed to track her down and she’s going to able to live with her birth family at last! However, on the car ride to her new home her father explains a few things to her to the effect that her mother was involved in some kind of accident and isn’t quite right in the head. Things get weirder when they arrive at the house only to be greated by the guys from the morgue who’ve just arrived to take charge of a maid who’s apparently dropped dead!

Little Sayuri has had it pretty tough up to now growing up in an orphanage run by Catholic nuns, but her long lost father has finally managed to track her down and she’s going to able to live with her birth family at last! However, on the car ride to her new home her father explains a few things to her to the effect that her mother was involved in some kind of accident and isn’t quite right in the head. Things get weirder when they arrive at the house only to be greated by the guys from the morgue who’ve just arrived to take charge of a maid who’s apparently dropped dead!

Released in 1949, The Invisible Man Appears (透明人間現る, Toumei Ningen Arawaru) is the oldest extant Japanese science fiction film. Loosely based on the classic HG Wells story The Invisible Man but taking its cues from the various Hollywood adaptations most prominently the Claude Rains version from 1933, The Invisible Man Appears also adds a hearty dose of moral guidance when it comes to scientific research.

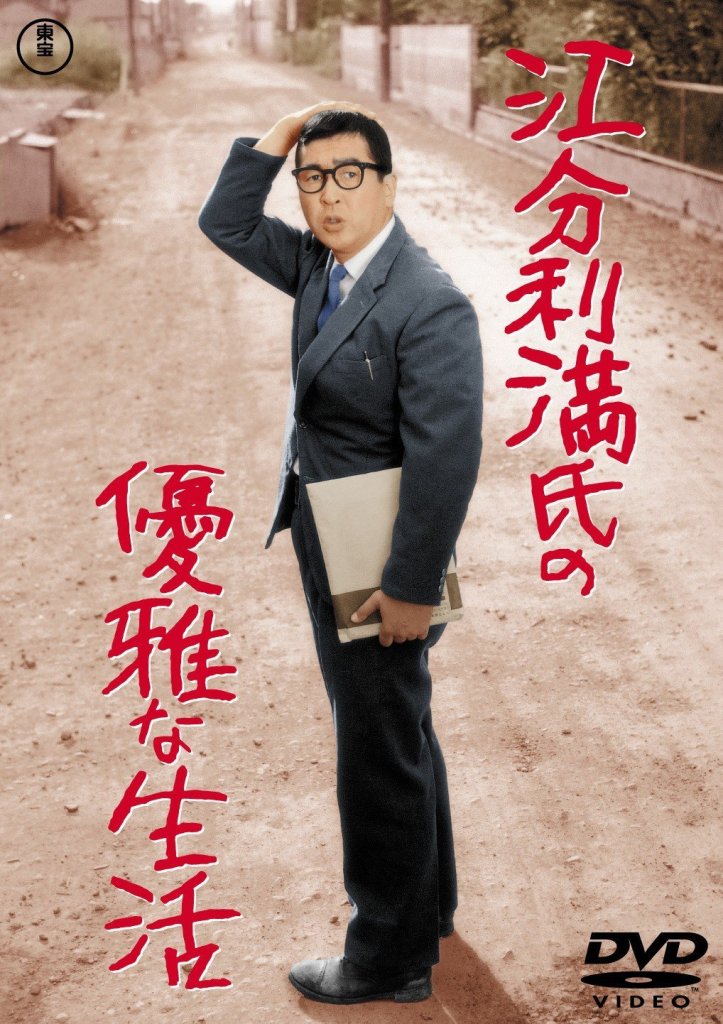

Released in 1949, The Invisible Man Appears (透明人間現る, Toumei Ningen Arawaru) is the oldest extant Japanese science fiction film. Loosely based on the classic HG Wells story The Invisible Man but taking its cues from the various Hollywood adaptations most prominently the Claude Rains version from 1933, The Invisible Man Appears also adds a hearty dose of moral guidance when it comes to scientific research. Kihachi Okamoto might be most often remembered for his samurai pictures including the landmark Sword of Doom but he had a long and extremely varied career which saw him tackle just about every conceivable genre and each from his own characteristically off-centre vantage point. The Elegant Life of Mr. Everyman (江分利満氏の優雅な生活, Eburi Man-shi no Yugana Seikatsu) sees him step into the world of the salaryman comedy as his hapless office worker reaches a dull middle age filled with drinking and regret imbued with good humour.

Kihachi Okamoto might be most often remembered for his samurai pictures including the landmark Sword of Doom but he had a long and extremely varied career which saw him tackle just about every conceivable genre and each from his own characteristically off-centre vantage point. The Elegant Life of Mr. Everyman (江分利満氏の優雅な生活, Eburi Man-shi no Yugana Seikatsu) sees him step into the world of the salaryman comedy as his hapless office worker reaches a dull middle age filled with drinking and regret imbued with good humour. A Japanese tragedy, or the tragedy of Japan? In Kinoshita’s mind, there was no greater tragedy than the war itself though perhaps what came after was little better. Made only eight years after Japan’s defeat, Keisuke Kinoshita’s 1953 film A Japanese Tragedy (日本の悲劇, Nihon no Higeki) is the story of a woman who sacrificed everything it was possible to sacrifice to keep her children safe, well fed and to invest some kind of hope in a better future for them. However, when you’ve had to go to such lengths to merely to stay alive, you may find that afterwards there’s only shame and recrimination from those who ought to be most grateful.

A Japanese tragedy, or the tragedy of Japan? In Kinoshita’s mind, there was no greater tragedy than the war itself though perhaps what came after was little better. Made only eight years after Japan’s defeat, Keisuke Kinoshita’s 1953 film A Japanese Tragedy (日本の悲劇, Nihon no Higeki) is the story of a woman who sacrificed everything it was possible to sacrifice to keep her children safe, well fed and to invest some kind of hope in a better future for them. However, when you’ve had to go to such lengths to merely to stay alive, you may find that afterwards there’s only shame and recrimination from those who ought to be most grateful. Loosely inspired by Julian Duvivier’s 1937 gangster movie Pépé le Moko, Toshio Masuda’s Red Pier (赤い波止場, Akai Hatoba) was designed as a vehicle for Nikkatsu’s rising star of the time, Yujiro Ishihara – later to become the icon of the Sun Tribe generation. On paper it sounds like a fairly conventional plot – young turk of a gangster comes to town to off a guy, sees said guy killed in an “accident”, and shrugs it off as one of life’s little ironies only to accidentally become acquainted with and fall head over heals for the dead guy’s sister. So far, so film noir yet Masuda adds enough of his own characteristic touches to keep things interesting.

Loosely inspired by Julian Duvivier’s 1937 gangster movie Pépé le Moko, Toshio Masuda’s Red Pier (赤い波止場, Akai Hatoba) was designed as a vehicle for Nikkatsu’s rising star of the time, Yujiro Ishihara – later to become the icon of the Sun Tribe generation. On paper it sounds like a fairly conventional plot – young turk of a gangster comes to town to off a guy, sees said guy killed in an “accident”, and shrugs it off as one of life’s little ironies only to accidentally become acquainted with and fall head over heals for the dead guy’s sister. So far, so film noir yet Masuda adds enough of his own characteristic touches to keep things interesting.