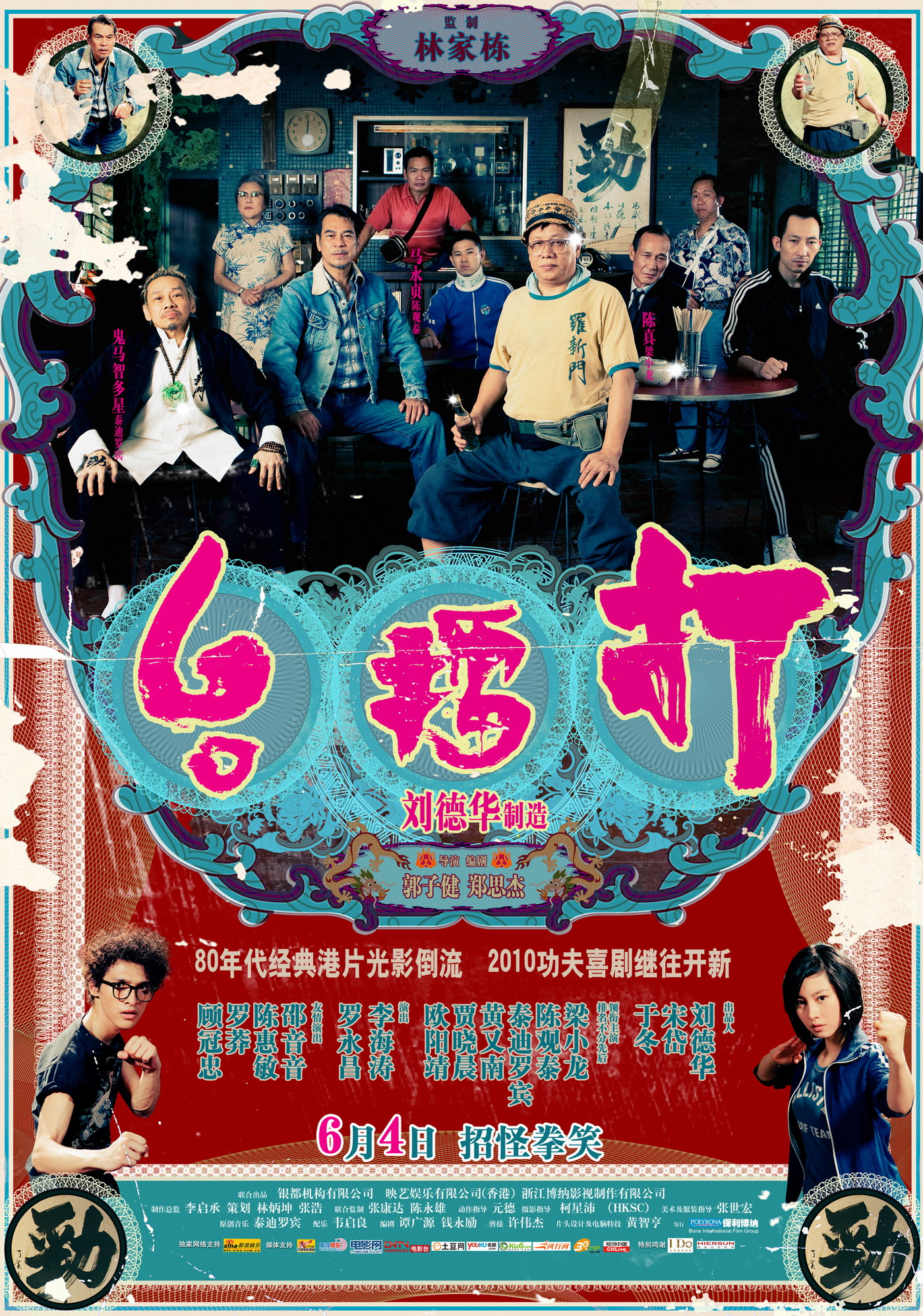

A former badminton champ begins to rediscover herself after being permanently banned for bullying behaviour when charged with coaching a bunch of former bank robbers in Derek Kwok & Henri Wong’s zany sports comedy Full Strike (全力扣殺). Dedicated to “all the beautiful losers”, the film is less about literal winning as it is about learning to turn one’s life around in moments of profound despair and draw strength from even non-literal victories in simply refusing to be looked down or belittled.

It’s ironic in a sense that Dan (Ekin Cheng Yee-Kin), Kun (Wilfred Lau Ho-Lung), and Chiu (Edmond Leung Hon-Man) became bank robbers because they didn’t want to be bullied having grown up as friendless orphans. Former badminton champ Kau Sau (Josie Ho Chiu-Yee), meanwhile, was such as tyrannical diva that she gained the nickname “The Beast” before being banned because of her unsportsmanlike behaviour and treatment of her long-suffering assistant. But cast out of the sports world, she’s become a dejected layabout not quite working in her brother’s restaurant and otherwise hiding out from the world. Her life changes when she’s publicly mocked after running into her former assistant who has since gone to take her position as a reigning champion. Running out into the night, she spots a shuttle-cock-shaped meteor and is chased to a badminton club by what she assumes is an “alien” but might have just been a frightened homeless man.

In any case, she takes it as a sign she should pick up a racket once again which as Dan later points out she probably wanted to do anyway and was just waiting for an excuse. He can’t explain why he chose the unlikely path of becoming a badminton player to help him turn over a new leaf after leaving prison but reflects that perhaps you don’t really need a reason only the desire to change. Dan, Kun, and Chiu all developed disabilities as a result of their life of crime but slowly discover that they can actually help them on the court in a literal process of making the most of their life experiences no matter how negative they might have assumed them to be while Kau Sau similarly regains her self esteem while acknowledging the destructive patterns of her previous behaviour careful never to bully her new teammates as they all square off against her bullying cousin “nipple sucking Cheung” (Ronald Cheng Chung-Kei) who tries to use his newfound wealth to cover up a lack of skill by hiring Kau Sau’s old teammate.

Cheung is also trying to overcome low self-esteem and is later forced to realise that becoming a champion won’t really change that much about how he sees himself, though apparently still relying on an ever capable middle-aged woman to fight (literally) his battles for him. Meanwhile, the gang are coopted by a media mogul hoping to make an inspirational documentary about them but also manipulating their lives and hyper fixating on their criminal pasts to the point of staging a fake arrest as they enter the stadium for a competition. Doubting the chances of success in setting up new lives for themselves as badminton players, Chiu is drawn back towards a life of crime while feeling somewhat distanced from the team as a tentative romance between Kau Sau and Dan seems to fall otherwise flat.

A throwback to classic mou lei tau nonsense comedy, the zany gags come thick and fast but are at times over reliant on low humour while the central premise of staking everything on an “unexciting” game like badminton perhaps wears a little thin by the time it gets to the high stakes finale with the heroes fighting twin battles squaring off against their traumatic pasts rather than the literal opponents in front of them. Winning becomes a kind of irrelevance when the contest was within the self. Each rediscovering the spark of life, the players rediscover the will to live while bonding as a team and sticking to their training in pursuit of their goal. Kwok and Wong lay it on a little thick with the martial arts parody in the uphill battle to master badminton but otherwise lend a poignant sense of warmth and genuine goodwill in sympathy with the underdogs’ quest if not quite to win then to own their loserdom on their on terms in reclaiming their self-respect and dignity.

Full Strike is available to stream in the UK until 30th June as part of this year’s Odyssey: A Chinese Cinema Season.

Original trailer (Traditional Chinese / English subtitles)

Kung fu movies – they don’t make ‘em like they used to, except when they do. Kung Fu Killer (一個人的武林, AKA Kung Fu Jungle) is equal parts homage and farewell as its ageing star, Donnie Yen, prepares to graduate to the role of master rather than rebellious pupil. What it also is, is a battle for the soul of kung fu. Just how “martial” should a martial art be? Is it, as our antagonist tells us, worthless with no death involved or will our hero prove the spiritual and mental benefits which come with its rigorous training and inner centring transcend its original purpose? Of course most of this is just posturing in the background of a lovingly old fashioned fight fest complete with a non-sensical plot structure motivated by increasingly elaborate set pieces.

Kung fu movies – they don’t make ‘em like they used to, except when they do. Kung Fu Killer (一個人的武林, AKA Kung Fu Jungle) is equal parts homage and farewell as its ageing star, Donnie Yen, prepares to graduate to the role of master rather than rebellious pupil. What it also is, is a battle for the soul of kung fu. Just how “martial” should a martial art be? Is it, as our antagonist tells us, worthless with no death involved or will our hero prove the spiritual and mental benefits which come with its rigorous training and inner centring transcend its original purpose? Of course most of this is just posturing in the background of a lovingly old fashioned fight fest complete with a non-sensical plot structure motivated by increasingly elaborate set pieces.