“Oldies are still the best,” one bad guy tells another while listening to a retro pop song about the inability to distinguish good from evil, “life was simpler back then.” Jason Kwon’s I Did it My Way (潛行) is in many ways an attempt to recapture the action classics of the 90s starring many of the same A-listers though they are all 30 years older and in some cases really ageing out of the kinds of roles they’re accustomed to playing in these kinds of films. Nevertheless, the action is updated for the contemporary era in its unsubtle messaging that drugs and cyber crime are bad, while the police are definitely good and will always win.

Indeed, barrister George Lam (Andy Lau Tak-wah) is not a particularly sympathetic villain and is given little justification for his crimes save doing things his way. Cybercrime specialist Eddie Fong (Edward Peng Yu-Yan) isn’t terribly sympathetic either, but mostly because of his bullheaded earnestness. Chung Kam-ming (Simon Yam Tat-wah) asks him to work with regular narcotics cop Yuen (Lam Suet), but Eddie originally refuses, insisting that they formed their new cybercrimes squad because the “old ways” weren’t working, so it’s better that they keep their investigations separate, which is of course quite rude to Yuen especially as he goes on to add that Chung’s only asked him out of politeness and professional deference. Chung, however, reminds them that they’re all part of one big family and should learn to work together.

One might think that a criminal enterprise is also a kind of family, but it’s shown to be illegitimate in comparison to that of the police. Yuen’s undercover agent, Sau Ho (Gordon Lam Ka-tung), has a family he’s trying to protect, as does Lam who is about to marry his much younger pregnant girlfriend. For them, family is also a weakness because it gives them a reason to be afraid not to mention something to lose. Beginning to suspect him, Lam uses Sau Ho’s wife and son as leverage, symbolically taking them hostage along with Sau Ho’s promised future that would allow him to emigrate for a life of freedom under a new identity.

Like the song says, Sau Ho is also struggling to define his identity as an undercover cop caught between his original desire to fight crime and the criminal lifestyle he’s been forced to live which leaves him never quite sure what side he’s actually on. Lam claims he only started dealing drugs after his girlfriend was raped and subsequently developed depression but that’s too late for him to turn back and so he’s gone all in. There is a kind of brotherhood that arises between them that’s permanently strained by their positioning on either side of this line and the inevitability of confrontation. Fong promises to save Sau Ho, but he failed to save most of their other undercover officers, while Sau Ho and Lam pledge to save each other, though the act of salvation could mean different things to each of them while both torn between their respective codes and the natural connection that’s been fostered by their long years working together as part of the gang.

The severing of this connection is again part of the price for their involvement with crime, with Lam led to believe that his choices have ironically robbed him of the pleasant familial future he dreamed of, while Sau Ho is returned to the familial embrace of the police force. Chung is repositioned as a benevolent father who can save his men, while Eddie too is forced to reintegrate by working with the other officers to fight cybercrimes which often intersect with those of other divisions. While the film includes several action sequences, it also insists that the major battle takes place online between hackers and police computer specialists, dramatising these online fights with CGI to slightly better effect than 2023’s Cyber Heist but still struggling to move on from an outdated iconography of the web. Even so, it’s clear that crime never pays even if a policewoman asks herself if it’s really worth it on a trip to the police cemetery. The sun has come out once again, making the dividing line between good and evil clear if also reinforcing the paternalistic authority of law enforcement under which living life “my way” will never be tolerated.

I Did It My Way is available digitally in the US courtesy of Well Go USA.

Trailer (English subtitles)

As it stands, contemporary Chinese cinema is veering dangerously close to Monkey King fatigue. Stephen Chow brought his particular sensibilities to the classic Journey to the West before Donnie Yen put on a monkey suit for

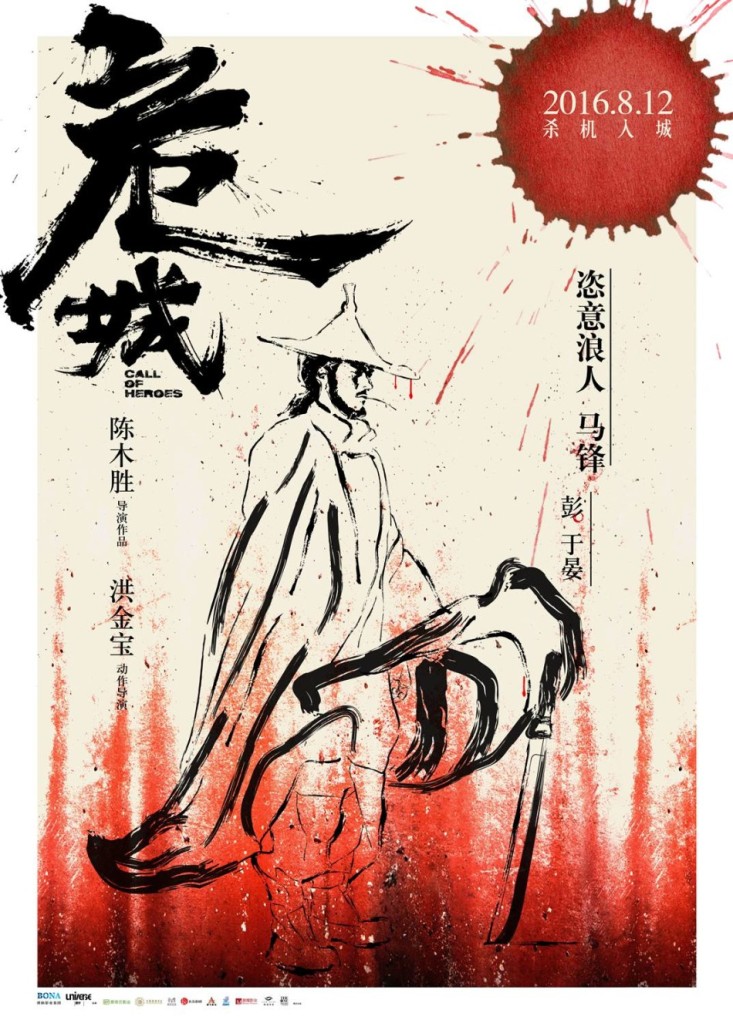

As it stands, contemporary Chinese cinema is veering dangerously close to Monkey King fatigue. Stephen Chow brought his particular sensibilities to the classic Journey to the West before Donnie Yen put on a monkey suit for  A blast from the past in more ways than one, Benny Chan’s Call of Heroes (危城, Wēi Chéng) is a western in disguise though one filtered through Akira Kurosawa and Sergio Leone more than John Ford. Filled with Morricone-esque musical riffs and poncho wearing reluctant heroes, Chan’s bounce back to the post-revolutionary warlord era is one pregnant with contemporary echoes yet totally unafraid to add a touch of uncinematic darkness to its wisecracking world.

A blast from the past in more ways than one, Benny Chan’s Call of Heroes (危城, Wēi Chéng) is a western in disguise though one filtered through Akira Kurosawa and Sergio Leone more than John Ford. Filled with Morricone-esque musical riffs and poncho wearing reluctant heroes, Chan’s bounce back to the post-revolutionary warlord era is one pregnant with contemporary echoes yet totally unafraid to add a touch of uncinematic darkness to its wisecracking world. Cold War 2 (寒戰II) arrives a whole four years after the original

Cold War 2 (寒戰II) arrives a whole four years after the original