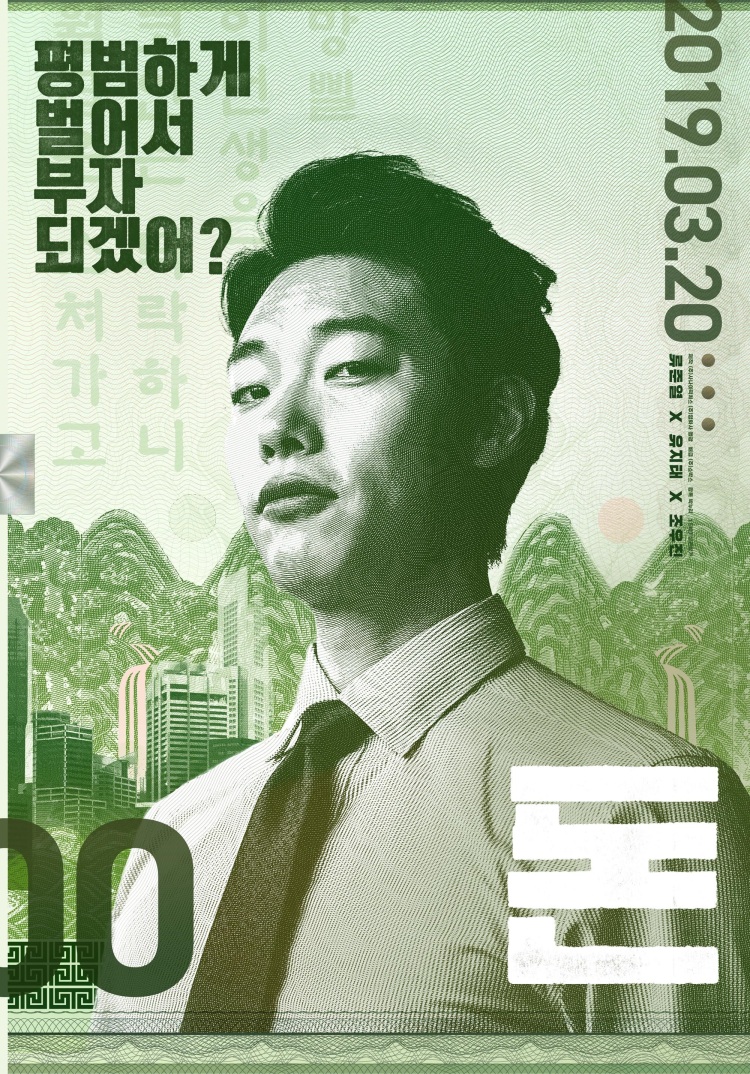

“Could you ask him something for me,” the beleaguered yet victorious protagonist of Park Noo-ri’s Money (돈, Don) eventually asks, “what was he going to use the money for?”. Wealth is, quite literally it seems, a numbers game for the villainous Ticket (Yoo Ji-tae) whose favourite hobby is destabilising the global stock market just for kicks. As for Cho Il-hyun (Ryu Jun-yeol), well, he just wanted to get rich, but where does getting rich get you in the end? There’s only so much money you can spend and being rich can make you lonely in ways you might not expect.

“Could you ask him something for me,” the beleaguered yet victorious protagonist of Park Noo-ri’s Money (돈, Don) eventually asks, “what was he going to use the money for?”. Wealth is, quite literally it seems, a numbers game for the villainous Ticket (Yoo Ji-tae) whose favourite hobby is destabilising the global stock market just for kicks. As for Cho Il-hyun (Ryu Jun-yeol), well, he just wanted to get rich, but where does getting rich get you in the end? There’s only so much money you can spend and being rich can make you lonely in ways you might not expect.

Unlike most of his fellow brokers, Cho Il-hyun is an ordinary lad from the country. His parents own a small raspberry farm and he didn’t graduate from an elite university or benefit from good connections, yet somehow he’s here and determined to make a success of himself. In fact, his only selling point is that he’s committed the registration numbers of all the firms on the company books to memory, and his ongoing nervousness and inferiority complex is making it hard for him to pick up the job. A semi-serious rookie mistake lands the team in a hole and costs everyone their bonuses, which is when veteran broker Yoon (Kim Min-Jae) steps in to offer Il-hyun a way out through connecting him with a shady middle-man named “The Ticket” who can set him up with some killer deals to get him back on the board.

Il-hyun isn’t stupid and he knows this isn’t quite on the level, but he’s desperate to get into the elite financial world and willing to cheat to make it happen. As might be expected his new found “success” quickly goes to his head as he “invests” in swanky apartments and luxury accessories, while his sweet and humble teacher girlfriend eventually dumps him after he starts showering her with expensive gifts and acting like an entitled elitist. It’s not until some of his fellow brokers who also seem to have ties to Ticket start dying in mysterious circumstances that Il-hyun begins to wonder if he might be in over his head.

Unlike other similarly themed financial thrillers, it’s not the effects of stock market manipulation on ordinary people which eventually wake Il-hyun up from his ultra capitalist dream (those are are never even referenced save a brief reflective shot at the end), but cold hard self-interest as he finally realises he is just a patsy Ticket can easily stub out when he’s done with him. Yoon only hooked him up in the first place because he knew he’d be desperate to take the bait in order to avoid repeated workplace humiliation and probably being let go at the end of his probationary period. What he’s chasing isn’t just “money” but esteem and access to the elite high life that a poor boy from a raspberry farm might have assumed entirely out of his reach.

It’s difficult to escape the note of class-based resentment in Il-hyun’s sneering instruction to his mother that she should “stop living in poverty” when she has the audacity to try and offer him some homemade chicken soup from ancient Tupperware, and it’s largely a sense of inferiority which drives him when he eventually decides to take his revenge on the omnipotent Ticket. Yet there’s a strangely co-dependent bond between the two men which becomes increasingly difficult pin down as they wilfully dance around each other.

The world of high finance is, unfortunately, a very male and homosocial one in which business is often conducted in night-clubs and massage parlours surrounded by pretty women. There is only one female broker on Il-hyun’s team. The guys refer to her as “Barbie” and gossip about how exactly she might have got to her position while she also becomes a kind of trophy conquest for Il-hyun as he climbs the corporate ladder. Meanwhile, there is also an inescapably homoerotic component to Il-hyun’s business dealings which sees him flirt and then enjoy a holiday (b)romance with a Korean-American hedge fund manager (Daniel Henney) he meets at a bar in the Bahamas, and wilfully strip off in front of Ticket ostensibly to prove he isn’t wearing a wire while dogged financial crimes investigator Ji-cheol (Jo Woo-jin) stalks him with the fury of a jilted lover.

Obsessed with “winning” in one sense or another, Il-hyun does not so much redeem himself as simply emerge victorious (though possibly at great cost). Even his late in the game make up with Chaebol best friend Woo-sung (Kim Jae-young), who actually turns out to be thoroughly decent and principled (perhaps because unlike Il-hyun he was born with wealth, status, and a good name and so does not need to care about acquiring them), is mostly self-interest rather than born of genuine feeling. In answer to some of Il-hyun’s early qualms, Ticket tells him that in finance the border between legal and illegal is murky at best and it may in fact be “immoral” not to exploit it. What Il-hyun wanted wasn’t so much “money” but what it represents – freedom, the freedom from “labour” and from from the anxiety of poverty. Life is long and there are plenty of things to enjoy, he exclaims at the height of his superficial success, but the party can only last so long. What was the money for? Who knows. Really, it’s beside the point.

Money was screened as part of the 2019 Fantasia International Film Festival.

International trailer (English subtitles)

Up until very recently, many of us lucky enough to live in nations with entrenched labour laws have had the luxury of taking them for granted. Mandated breaks, holidays, sick pay, strictly regulated working hours and overtime directives – we know our rights, and when we feel they’re being infringed we can go to our union representatives or a government ombudsman to get our grievances heard. If they won’t listen, we have the right to strike. Anyone who’s been paying attention to recent Korean cinema will know that this is not the case everywhere and even trying to join a union can not only lead to charges of communism and loss of employment but effective blacklisting too. Cart (카트), inspired by real events, is the story of one group of women’s attempt to fight back against an absurdly arbitrary and cruel system which forces them to accept constant mistreatment only to treat their contractual agreements with cavalier contempt.

Up until very recently, many of us lucky enough to live in nations with entrenched labour laws have had the luxury of taking them for granted. Mandated breaks, holidays, sick pay, strictly regulated working hours and overtime directives – we know our rights, and when we feel they’re being infringed we can go to our union representatives or a government ombudsman to get our grievances heard. If they won’t listen, we have the right to strike. Anyone who’s been paying attention to recent Korean cinema will know that this is not the case everywhere and even trying to join a union can not only lead to charges of communism and loss of employment but effective blacklisting too. Cart (카트), inspired by real events, is the story of one group of women’s attempt to fight back against an absurdly arbitrary and cruel system which forces them to accept constant mistreatment only to treat their contractual agreements with cavalier contempt.

Review of Lee Il-hyeong’s A Violent Prosecutor first published by

Review of Lee Il-hyeong’s A Violent Prosecutor first published by