The Girl Who Leapt Through Time is a perennial favourite in its native Japan. Yasutaka Tsutsui’s original novel was first published back in 1967 giving rise to a host of multimedia incarnations right up to the present day with Mamoru Hosoda’s 2006 animated film of the same name which is actually a kind of sequel to Tsutsui’s story. Arguably among the best known, or at least the best loved to a generation of fans, is Hausu director Nobuhiko Obayashi’s 1983 movie The Little Girl Who Conquered Time (時をかける少女, Toki wo Kakeru Shoujo) which is, once again, a Kadokawa teen idol flick complete with a music video end credits sequence.

The Girl Who Leapt Through Time is a perennial favourite in its native Japan. Yasutaka Tsutsui’s original novel was first published back in 1967 giving rise to a host of multimedia incarnations right up to the present day with Mamoru Hosoda’s 2006 animated film of the same name which is actually a kind of sequel to Tsutsui’s story. Arguably among the best known, or at least the best loved to a generation of fans, is Hausu director Nobuhiko Obayashi’s 1983 movie The Little Girl Who Conquered Time (時をかける少女, Toki wo Kakeru Shoujo) which is, once again, a Kadokawa teen idol flick complete with a music video end credits sequence.

As in the novel, the story centres around regular high school girl Kazuko Yoshiyama (Tomoyo Harada). She has two extremely close male friends (generally a recipe for disaster, or at least for melodrama but this is not that kind of story) – Horikawa and Fukamachi, and one Saturday while all three are charged with cleaning up the schoolroom, Kazuko ventures into the science lab where she sees a beaker on the floor emitting thick white smoke which smells strongly of lavender causing her to pass out. Everyone seems to think it’s either hunger, anaemia, or that old favourite “woman’s troubles” but from this day on Kazuko’s life begins to change. The same day repeats itself over and over again with minor differences and Kazuko also begins to experience multilayered dreams in which her friends are in some kind of peril.

Tsutsui’s original novel was a Kadokawa Shoten property (though first published 15 years previously) which made it a natural fit for the Kadokawa effect so when legendary idol master Haruki Kadokawa found an idol he was particularly taken with in Tomoyo Harada the stars aligned. Obayashi set the story in his own hometown, the pleasantly old fashioned port village of Onomichi, which adds a nicely personal feel to his take on the original story. Although The Little Girl Who Conquered Time is an adaptation of a classic novel, many of Obayashi’s regular concerns are present from the wistful tone to the transience of emotion and the importance of memory.

Kazuko is another of Obayashi’s young women at a crossroads as she finds herself wondering what to do with the rest of her life. The original timeline seems to point to a romance and possibly a life of pleasant, if dull, domesticity with one of her best friends but with this time travelling intrusion everything diverges. Though assured that she will not remember most of the strange events that have been happening to her, something of her adventures seems to have stuck in Kazuko’s mind even if she couldn’t quite say why. Much to the consternation of her mother, Kazuko’s purpose in life begins to lean to towards the scientific rather than the romantic, almost as if she’s waiting for the return of someone whom she has no recollection of having met.

Obayashi once again uses conflicting colour schemes to anchor his story. Beginning with black and white as Kazuko has her first encounter with someone she’s known all her life under the brightly shining stars, he gradually re-introduces us to the “real” world through sporadically adding colour during her bus ride home to her small town which does have a noticeably more old fashioned aesthetic when compared to Tokyo set features of the era. The effects are highly stylised and very much of their time including the celebrated time travel sequence which has Kazuko framed by a neon blue halo. The most touching sequence occurs near the end of the film in which Kazuko crosses paths with a familiar face that she doesn’t quite recognise, the camera perspective actively changes physically pulling us away from the encounter until Kazuko turns around and walks away in the opposite direction and into yet another empty corridor.

Tomoyo Harada developed into a fine actress with a long standing and successful career in both television and feature films as well as releasing a number of full length albums. As is usual with this kind of film she also sings the theme tune which has the same title as the movie though in an unusual movie Obayashi includes a music video retelling of the events of the film over the end credits featuring all of the cast helping Harada to perform the song with silly grins on their faces all the way through. Harada proves herself much more adept at convincingly carrying a feature length movie than some of her fellow idols but the same cannot be said for many of her co-stars though she is well backed up by established adult cast members including Ittoku Kishibe as Kazuko’s romantically distressed teacher.

The Little Girl Who Conquered Time is first and foremost a Kadokawa idol movie and has all the hallmarks of this short lived though extremely successful genre. Necessarily very much of its time, the film has taken on an additional layer of nostalgic charm on top of that which has been deliberated injected into it. Nevertheless, in keeping with Obayashi’s other work The Little Girl Who Conquered Time has a melancholic, wistful tone which is sentimental at times but, crucially, always sincere.

Original trailer (no subtitles)

And here’s the famous music video for the title song (which is of course sung by Tomoyo Harada herself). English Subtitles!

If you’re going on the run you might as well do it in style. Wait, that’s terrible advice isn’t it? Perhaps there’s something to be said for planning a cunning double bluff by becoming so flamboyant that everyone starts ignoring you out of a mild sense of embarrassment but that’s quite a risk for someone whose original gamble has so obviously gone massively wrong. An adaptation of a manga, Katsuhito Ishii’s debut feature Sharkskin Man and Peach Hip Girl (鮫肌男と桃尻女, Samehada Otoko to Momojiri Onna) follows a mysterious criminal trying to head off the gang he just stole a bunch of money from whilst also accompanying a strange young girl, also on the run but from her perverted, hotel owning “uncle” who has also sent an equally eccentric hitman after the absconding pair with instructions to bring her back.

If you’re going on the run you might as well do it in style. Wait, that’s terrible advice isn’t it? Perhaps there’s something to be said for planning a cunning double bluff by becoming so flamboyant that everyone starts ignoring you out of a mild sense of embarrassment but that’s quite a risk for someone whose original gamble has so obviously gone massively wrong. An adaptation of a manga, Katsuhito Ishii’s debut feature Sharkskin Man and Peach Hip Girl (鮫肌男と桃尻女, Samehada Otoko to Momojiri Onna) follows a mysterious criminal trying to head off the gang he just stole a bunch of money from whilst also accompanying a strange young girl, also on the run but from her perverted, hotel owning “uncle” who has also sent an equally eccentric hitman after the absconding pair with instructions to bring her back. Like many directors during the 1980s, Nobuhiko Obayashi was unable to resist the lure of a Kadokawa teen movie but His Motorbike, Her Island (彼のオートバイ彼女の島, Kare no Ootobai, Kanojo no Shima) is a typically strange 1950s throwback with its tale of motorcycle loving youngsters and their ennui filled days. Switching between black and white and colour, Obayashi paints a picture of a young man trapped in an eternal summer from which he has no desire to escape.

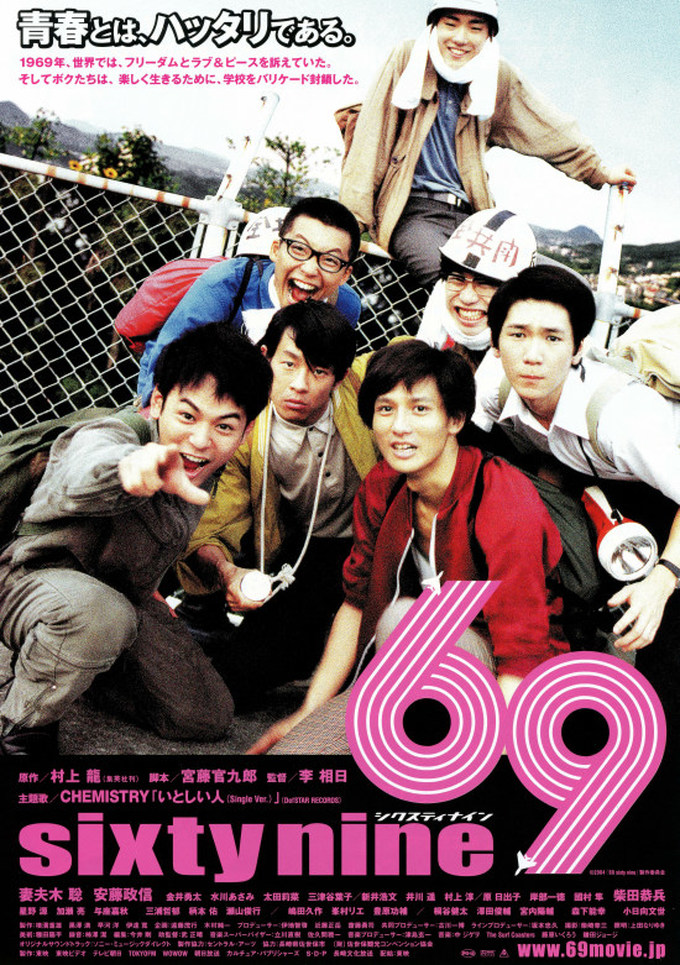

Like many directors during the 1980s, Nobuhiko Obayashi was unable to resist the lure of a Kadokawa teen movie but His Motorbike, Her Island (彼のオートバイ彼女の島, Kare no Ootobai, Kanojo no Shima) is a typically strange 1950s throwback with its tale of motorcycle loving youngsters and their ennui filled days. Switching between black and white and colour, Obayashi paints a picture of a young man trapped in an eternal summer from which he has no desire to escape. Ryu Murakami is often thought of as the foremost proponent of Japanese extreme literature with his bloody psychological thriller/horrifying love story

Ryu Murakami is often thought of as the foremost proponent of Japanese extreme literature with his bloody psychological thriller/horrifying love story

East has been meeting West in the movies from time immemorial and though it’s often assumed that the traffic is only running in one direction, in reality the river runs both ways. Kihachi Okamoto was always fairly open about his love of Hollywood westerns, particularly those of John Ford, and even mixed a fair amount of wild west style action to his 1959 Manchurian war movie, Desperado Outpost. Returning to the theme almost 40 years later in East Meets West (イースト・ミーツ・ウエスト), Okamoto retains his wry, ironic eye but adopts a tone much more in keeping with the slightly silly exploitation cowboy movies of the ‘70s.

East has been meeting West in the movies from time immemorial and though it’s often assumed that the traffic is only running in one direction, in reality the river runs both ways. Kihachi Okamoto was always fairly open about his love of Hollywood westerns, particularly those of John Ford, and even mixed a fair amount of wild west style action to his 1959 Manchurian war movie, Desperado Outpost. Returning to the theme almost 40 years later in East Meets West (イースト・ミーツ・ウエスト), Okamoto retains his wry, ironic eye but adopts a tone much more in keeping with the slightly silly exploitation cowboy movies of the ‘70s. Article 39 of Japan’s Penal Code states that a person cannot be held responsible for a crime if they are found to be “insane” though a person who commits a crime during a period of “diminished responsibility” can be held accountable and will receive a reduced sentence. Yoshimitsu Morita’s 1999 courtroom drama/psychological thriller Keiho (39 刑法第三十九条, 39 Keiho Dai Sanjukyu Jo) puts this very aspect of the law on trial. During this period (and still in 2016) Japan does nominally have the death penalty (though rarely practiced) and it is only right in a fair and humane society that those people whom the state deems as incapable of understanding the law should receive its protection and, if necessary, assistance. However, the law itself is also open to abuse and as it’s largely left to the discretion of the psychologists and lawyers, the judgement of sane or insane might be a matter of interpretation.

Article 39 of Japan’s Penal Code states that a person cannot be held responsible for a crime if they are found to be “insane” though a person who commits a crime during a period of “diminished responsibility” can be held accountable and will receive a reduced sentence. Yoshimitsu Morita’s 1999 courtroom drama/psychological thriller Keiho (39 刑法第三十九条, 39 Keiho Dai Sanjukyu Jo) puts this very aspect of the law on trial. During this period (and still in 2016) Japan does nominally have the death penalty (though rarely practiced) and it is only right in a fair and humane society that those people whom the state deems as incapable of understanding the law should receive its protection and, if necessary, assistance. However, the law itself is also open to abuse and as it’s largely left to the discretion of the psychologists and lawyers, the judgement of sane or insane might be a matter of interpretation. It used to be that movies about marital discord typically ended in a tearful reconciliation and the promise of greater love and understanding between two people who’ve taken a vow to spend their lives together. These endings reinforce the importance of the traditional family which is, after all, what a lot of Japanese cinema is based on. However, times have changed and now there’s more room for different narratives – stories of women who’ve had enough with their useless, deadbeat man children and decide to make a go of things on their own.

It used to be that movies about marital discord typically ended in a tearful reconciliation and the promise of greater love and understanding between two people who’ve taken a vow to spend their lives together. These endings reinforce the importance of the traditional family which is, after all, what a lot of Japanese cinema is based on. However, times have changed and now there’s more room for different narratives – stories of women who’ve had enough with their useless, deadbeat man children and decide to make a go of things on their own.