Throughout Yoichi Sai’s All Under the Moon (月はどっちに出ている, Tsuki wa Dotchi ni Dete iru), an earnest taxi driver, Anbo (Akio Kaneda), repeatedly calls in to despatch to inform them that he’s become lost and has no idea where he is despite rocking up next to such prominent landmarks as Tokyo Tower and Mount Fuji. His confusion reflects that of the changing post-Bubble society in which those like him struggle to reorient themselves and find new direction just as the nation appears slow to recognise itself and adjust to a new reality.

It does seem that many of the drivers at Kaneda Taxi have themselves lost direction in their lives and are living very much on their margins while their rather deluded boss Sell is behaving like it’s still the Bubble dreaming of building a golf course and then a hotel to accommodate 2000 people. The Korean loan shark working with him alternately tells fellow Zainichi taxi driver Chun (Goro Kishitani) that he’s acquiring wealth to use for the reunification of Korea, and Sell that they are all children of capitalism, “Damn Reunification!”. At the wedding Chun attends, the guests take phone calls to deal with business and each remark on the precarious economic situation while one suggests that the North Korean association he represents is probably on the brink of failure joking that he fears they may sell their school and pocket the money.

Yet despite the economic turbulence, the country has been slow to accept the presence of workers from outside Japan and many, including those at the taxi firm, still face discrimination as does Chun himself by virtue of his Korean heritage. One Japanese employee also seems to face a good deal of stigmatisation simply because he has a speech impediment, while an older mechanic with a limp insists on calling an Iranian colleague by a similar sounding Japanese name while baselessly accusing him of theft. Hoso (Yoshiki Arizono), a man with mental health issues provoked by his previous career as a professional boxer in which he accidentally killed an opponent during a bout, is fond of saying “I hate Koreans, but I like you” while otherwise fixating on Chun as a dependable big brother figure and resentful enough when he starts dating a Filipina hostess, Connie (Ruby Moreno), who works at his mother’s bar to pound down the door of her flat and demand to be let in.

Chun himself is at least problematic and especially by the standards of today as he tries a series of crass pickup lines on Korean women at the wedding and then eventually forces a kiss on Connie not to mention physically striking her during a heated argument. He also insensitively tells her about his family’s tragic history in the war emphasising that citizens of Korea were abused for slave labour while seemingly unaware of the history of the Japanese occupation of the Philippines. Meanwhile, he also lies that his father was killed by the Japanese and that all his brothers died of malnutrition whereas they are (presumably) alive if possibly not so well in North Korea. His hard as nails mother (Moeko Ezawa) points out that she came to Japan at 10, while Connie counters that she came at 15, though their experiences have perhaps been very different leaving them somewhat at odds rather than sharing a kind of solidarity as otherwise echoed in the marginal status of each of the migrants who are similarly othered as merely not Japanese yet largely left to fend for themselves while facing possible exploitation and deportation.

Divisions exist even within the Korean population with guests at the wedding complaining that there have been too many long and boring speeches along with North Korean propaganda songs, claiming that it is discriminatory against South Koreans and finally being allowed to sing a South Korean folksong instead which is at least a good deal more lively. The gangsters leverage the idea of reuinifaction to carry out their scams while later claiming that they have been scammed by their Japanese backer who turned out to be more racist than they had first assumed. Yet as Chun says during one of his cheesy pickup attempts, what really has reunification got to do with them, the younger post-war generation who know no other homeland than Japan? He too flounders, caught between a series of names from “Tadao Kanda” to “Chun”, to the name which appears on his taxi license “Kang” the Korean pronunciation of character read “ga” Japanese which is only otherwise used in the word for ginger as pointed out by a slightly racist fare who goes on to remark that he doesn’t see the point of the “comfort women issue”. Chun has to grin and bear it while technically powerless despite being in the driver’s seat. Predictably, the prejudiced passenger also attempted to make a run for it rather than actually pay Chun his money. “I was born after the war too” Chun reminds him, “but we say after the liberation.”

Sai introduces us to the world of Kanda Taxis through a roving long shot around the carpark travelling from one employee to another before drifting up to management on the second floor. He returns to a similar scene near the film’s conclusion as the remaining workers playfully hose each other with water while literally watching their world burn. Yet for some at least it may be liberating experience, Chun finally gaining the courage to choose his own destination and go after something that he wants, even if it he does it in a characteristically problematic way, seemingly no longer worrying about where it might be taking him but content to simply drive in the direction of the moon.

Original trailer (no subtitles)

Chekhov’s The Cherry Orchard is more about the passing of an era and the fates of those who fail to swim the tides of history than it is about transience and the ever-present tragedy of the death of every moment, but still there is a commonality in the symbolism. Shun Nakahara’s The Cherry Orchard (櫻の園, Sakura no Sono) is not an adaptation of Chekhov’s play but of Akimi Yoshida’s popular 1980s shojo manga which centres on a drama group at an all girls high school. Alarm bells may be ringing, but Nakahara sidesteps the usual teen angst drama for a sensitively done coming of age tale as the girls face up to their liminal status and prepare to step forward into their own new era.

Chekhov’s The Cherry Orchard is more about the passing of an era and the fates of those who fail to swim the tides of history than it is about transience and the ever-present tragedy of the death of every moment, but still there is a commonality in the symbolism. Shun Nakahara’s The Cherry Orchard (櫻の園, Sakura no Sono) is not an adaptation of Chekhov’s play but of Akimi Yoshida’s popular 1980s shojo manga which centres on a drama group at an all girls high school. Alarm bells may be ringing, but Nakahara sidesteps the usual teen angst drama for a sensitively done coming of age tale as the girls face up to their liminal status and prepare to step forward into their own new era.

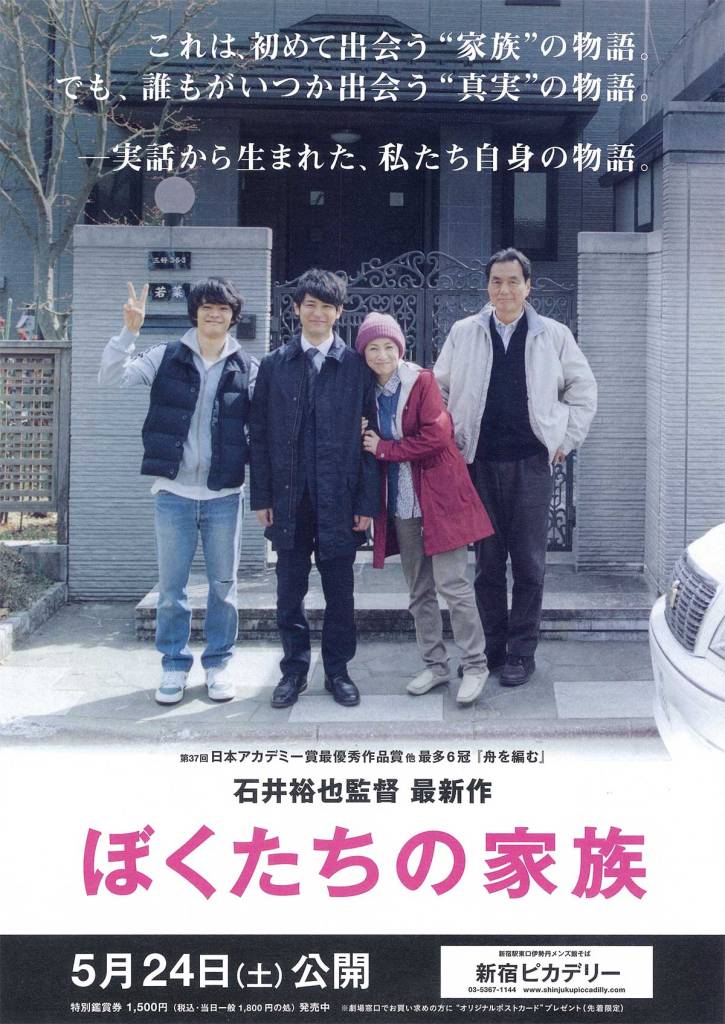

Yuya Ishii’s early work generally took the form of quirky social comedies, but underlying them all was that classic bastion of Japanese cinema, the family drama. If Ishii was in some senses subverting this iconic genre in his youthful exuberance, recent efforts have seen him come around to a more conventional take on the form which is often thought to symbolise his nation’s cinema. In Our Family Ishii is making specific reference to the familial relations of a father and two sons who orbit around the mother but also hints at wider concerns in a state of the nation address as regards the contemporary Japanese family.

Yuya Ishii’s early work generally took the form of quirky social comedies, but underlying them all was that classic bastion of Japanese cinema, the family drama. If Ishii was in some senses subverting this iconic genre in his youthful exuberance, recent efforts have seen him come around to a more conventional take on the form which is often thought to symbolise his nation’s cinema. In Our Family Ishii is making specific reference to the familial relations of a father and two sons who orbit around the mother but also hints at wider concerns in a state of the nation address as regards the contemporary Japanese family. Never one to be accused of clarity, Seijun Suzuki’s Capone Cries a Lot (カポネおおいになく, Capone Ooni Naku) is one of his most cheerfully bizarre movies coming fairly late in his career yet and neatly slotting itself in right after Suzuki’s first two Taisho era movies,

Never one to be accused of clarity, Seijun Suzuki’s Capone Cries a Lot (カポネおおいになく, Capone Ooni Naku) is one of his most cheerfully bizarre movies coming fairly late in his career yet and neatly slotting itself in right after Suzuki’s first two Taisho era movies,