According to the hero of Sora Hokimoto’s BAUS: The Ship’s Voyage Continues (BAUS 映画から船出した映画館, Eiga kara Funadeshita Eigakan), films are born of man’s battle against time and the desire to extend one moment into eternity. Yet his father was always looking for a new “tomorrow” and a path towards the future that ironically kept him from being fully in the present. Inspired by the memoirs of Takuo Honda, the film is effectively a people’s history of cinema culminating in 2014 with the closure of the Baus Town cinema amid a climate in which film itself seems to have entered a terminal decline.

Indeed, Takuo’s father Shigeo (Shota Sometani) becomes almost a ghost himself. Having come to Tokyo insisting that movies were his “tomorrow,” the war leaves him a shadow of his former self and a spectral presence in the auditorium. Though Takuo’s mother (Kaho) and others at the cinema have discovered a new community eating together every night after the final screening, Shigeo is often out drinking with the chamber of commerce and rarely returns home. Still looking for “tomorrow,” he appears lost for direction despite opening a new, more modern cinema fit for the post-war era.

As the mother of Shigeo’s wife Hama says, men are focused on past and future while it’s women who are forced to face the present leaving most of the more practical problems for Hama to deal with. Shigeo’s brother Hajime (Kazunobu Mineta) had perhaps been overly obsessed with the past and ultimately unable to move forward. After coming to Tokyo with Shigeo, he became an unsuccessful benshi only to be rendered obsolete by the arrival of talkies. Despite being drawn to the anti-capitalist rhetoric of the migrant workers, he later falls hard for militarism and becomes a casualty of the war both literally and spiritually. Shigeo laments the increasing censorship of the late 1930s complaining that it has become impossible to make or show films, but it’s little better afterwards as the Occupation forces push Hollywood movies at the expense of the European or Japanese.

Hajime had snapped back that entertainment wouldn’t change anything and that war purified the world, but Shigeo insists that films are a window from which the local population can learn about other lives and other places, a means of “building the heart” that might a save a soul. The older Takuo envisages a world in which watching a film normally or loving someone normally might become political acts in themselves. He weaves his personal history of film, which is also that of his family, with the political realities of the mid-20th century in which beautiful forests are cut down to make coffins for the endless dead and unexploded incendiaries lurk like ticking time bombs both literally and psychologically as, as one old man puts it, the nation’s struggles to reckon with its role in the war or its traumatic consequences.

Nevertheless, even if Takuo is closing Baus Town for reasons stemming from his own traumatic loss, he continues to look for tomorrow despite his old age. Asked what his dream was, he replies only that he wanted his children to have better lives than he did, though he worries he may have failed. In any case, he remains lost within the labyrinths of cinema. The building itself, originally surrounded by fields in a much smaller Kichijoji, becomes a haunted space in his memory, half dream and longed-for place of warmth and salvation in which he remains a small child searching for his father in the empty auditorium.

The name for Baus Town is taken from the bow and stern of a ship, echoing Takuo’s own search for other horizons and a constant process of moving through the world. He too is trying battle time and make a moment last an eternity while admitting that there’s nothing so beautiful as smoke in the projector beam. He asks his daughter if smoke, like movies, isn’t connected to the afterlife and there are ways in which Takuo has also become a ghost, both haunted and haunting while films are themselves a kind of other world of the living past and a way of communing with those no longer here. Taking over production after Shinji Aoyama passed away, Sora gives the film an elegiac, poetic quality while asking if cinemas too might be resurrected in the same way as film even as Takuo ponders new directions while continuing to sail ahead in search of tomorrow.

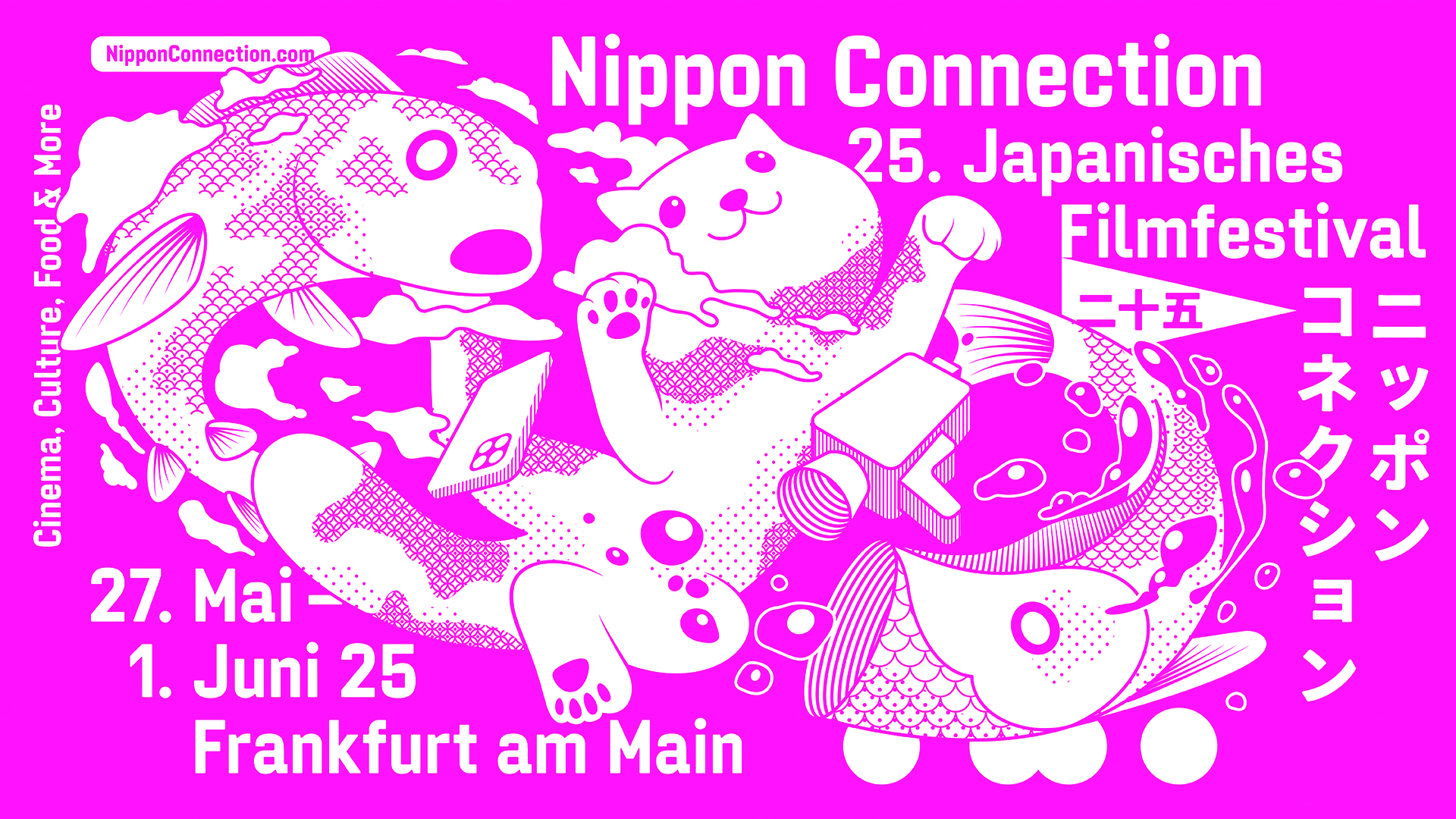

BAUS: The Ship’s Voyage Continues screened as part of this year’s Nippon Connection.

Original trailer (no subtitles)

Images: ©Honda Promotion BAUS/boid