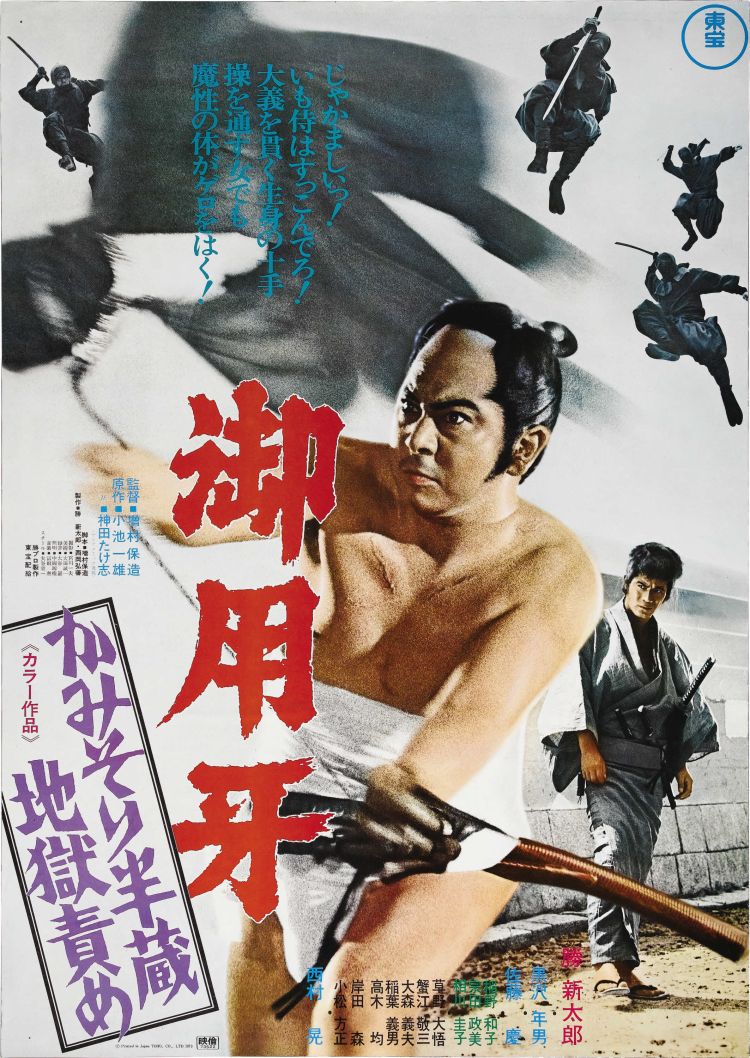

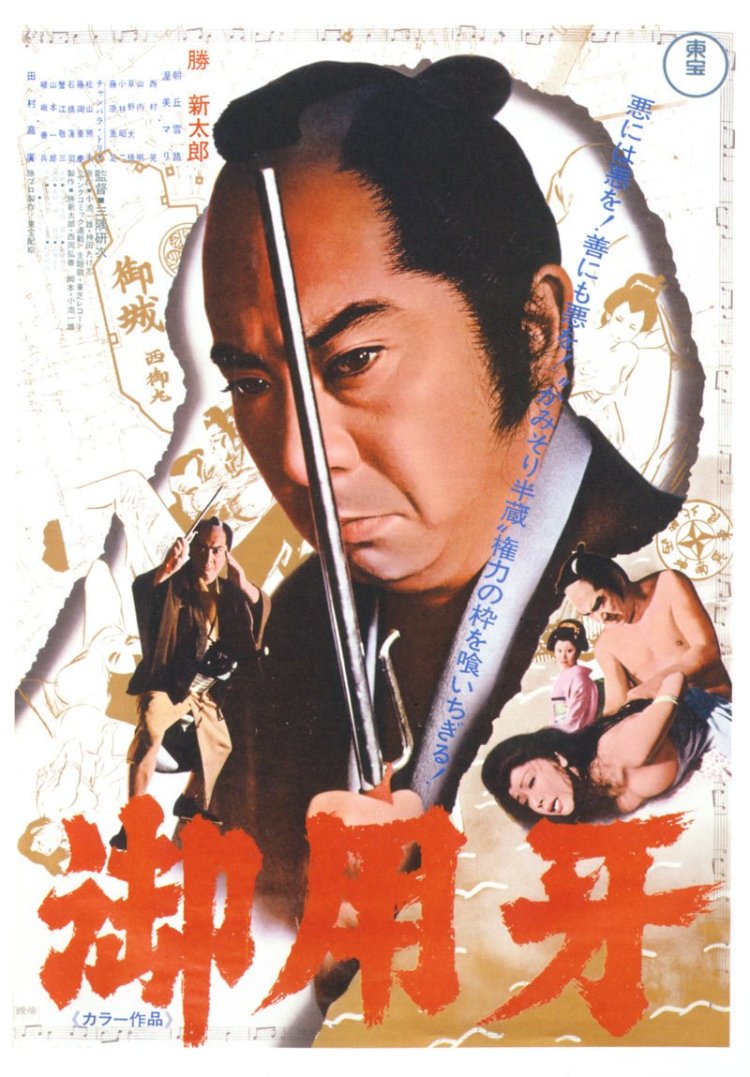

Yasuzo Masumura had spent the majority of his career at Daiei, but following the studio’s bankruptcy, he found himself out on his own as a freelance director for hire. That is perhaps how he came to direct this improbable entry in his filmography on the second of a trilogy of exploitation leading jidaigeki films for Toho. Essentially a vanity project for former Zatoichi star Shintaro Katsu who both produces and stars in the series, Hanzo the Razor: The Snare (御用牙 かみそり半蔵地獄責め , Goyokiba: Kamisori Hanzo Jigoku Zeme) is another tale of the well endowed hero of the Edo era protecting ordinary people from elite corruption, but Masumura, providing the script himself, bends it to his own will whilst maintaining the essential house style.

Yasuzo Masumura had spent the majority of his career at Daiei, but following the studio’s bankruptcy, he found himself out on his own as a freelance director for hire. That is perhaps how he came to direct this improbable entry in his filmography on the second of a trilogy of exploitation leading jidaigeki films for Toho. Essentially a vanity project for former Zatoichi star Shintaro Katsu who both produces and stars in the series, Hanzo the Razor: The Snare (御用牙 かみそり半蔵地獄責め , Goyokiba: Kamisori Hanzo Jigoku Zeme) is another tale of the well endowed hero of the Edo era protecting ordinary people from elite corruption, but Masumura, providing the script himself, bends it to his own will whilst maintaining the essential house style.

Hanzo (Shintaro Katsu) chases a pair of crooks right into the path of treasury officer Okubo. As expected, the lord and his retainers kick off but Hanzo won’t back down, shouting loudly about honour and justice much to his lord’s displeasure. Eventually Hanzo takes the two crooks into custody and they tell him exactly what’s happened to them this evening – they snuck over from the next village to steal some rice from the watermill but they found a dead girl in there and so they were running away in terror. Hanzo investigates and finds the partially clothed body still lying in the mill untouched but when he takes a closer look it seems the girl wasn’t exactly murdered but has died all alone after a botched abortion. Realising she smells of the incense from a local temple, Hanzo gets on the case but once again ends up uncovering a large scale government conspiracy.

Though it might not immediately seem so, Masumura’s key themes are a perfect fit for the world of Hanzo. In his early contemporary films such as Giants & Toys and Black Test Car, Masumura had painted a grim view of post-war society in which systemic corruption, personal greed, and selfishness had destroyed any possibility of well functioning human relationships. It was Masumura’s belief that true freedom and individuality was not possible within a conformist society such as Japan’s but this need for personal expression was possible through sexuality. Sex is both a need and a trap as Masumura’s (often) heroines chase their freedom through what essentially amounts to an illicit secret, using and manipulating the men around them in order to improve their otherwise dire lack of agency.

Hanzo’s investigation takes him into an oddly female world of intrigue in which a buddhist nun has been duped into becoming a middle-woman in a government backed scheme pimping innocent local girls to the highest bidder among a gang of wealthy local merchants. Hanzo berates the parents of the murdered girl for not having kept a better eye on her, but these misused women are left with no other recourse than the shady protection of others inhabiting the same world of corrupt transactions such as the local shamaness who has developed a “new method of abortion” just as Hanzo has developed a “new method of torture” which involves a bizarrely sexualised ritual in which both parties must be fully naked before she enacts penetration with her various instruments. Hanzo first tries more usual torture methods on the nun before indulging in his trademark tactic of trapping her in a net to be raised and lowered onto his oversize penis which he keeps in top notch by beating it with a stick and ramming it into a bag of rough uncooked rice.

Unlike the first film, the women are less ready to fall for Hanzo’s giant member. The nun complains loudly that her Buddhist vows of chastity are being violated while Hanzo’s later rape of the woman who runs the local mint is a much more violent affair. Hanzo grapples with her legs as she struggles, gasping as he opens his loincloth and reveals his surprisingly large appendage, once again playing into the fallacy that all women harbour some kind of rape fantasy. Hanzo has done this, he claims, to “calm her down”, because he could sense her sexual frustration and desperate need for male contact. To be fair to Hanzo, he does appear to be correct in his reading of the woman’s behaviour as she sheds her anxiety and becomes a firm devotee of the cult of Hanzo.

Meanwhile, political concerns bubble in the background as the main conspiracy revolves around consistent currency devaluations which are placing a stranglehold on the fortunes of the poor while their overlords, who are supposed to be protecting them, spend vast sums on claiming the virginity of innocent young girls. Hanzo may be a rapist himself (though he makes it clear that he derives no pleasure from his actions and only gives pleasure to the women involved), but he draws the line at the misuse of innocents, saving a little girl about to be violated by the master criminal Hamajima (Kei Sato) in a daring confrontation in which he boldly brings his own coffin, just in case.

Masumura broadly sticks to the Toho house style, but gone is the camp comedy of the first instalment with its giggly gossipers and humorous shots of Hanzo’s permanently erect penis. Instead he opts for an increase in sleazy voyeurism, filling the screen with female nudity whilst neatly implicating the male audience who enjoy such objectification by shooting from secretive angles as his collection of dirty old men crowd round a two way mirror to watch the lucky winner torture and abuse the soft young flesh they’ve just been bidding on. Like Sword of Justice, The Snare also ends with a slightly extraneous coda in which Hanzo settles a dispute with another official by means of a duel he would rather not have fought. Walking off bravely into the darkness, Hanzo utters only the word “idiot” for a man who wasted his life on petty samurai pride. Hanzo has better things to do, protecting the common man from just such men who place hypocritical ideas of pride and honour above general human decency in their need for domination through fear and violence over his own tenet of unrestrained pleasure.

Original trailer (no subtitles)

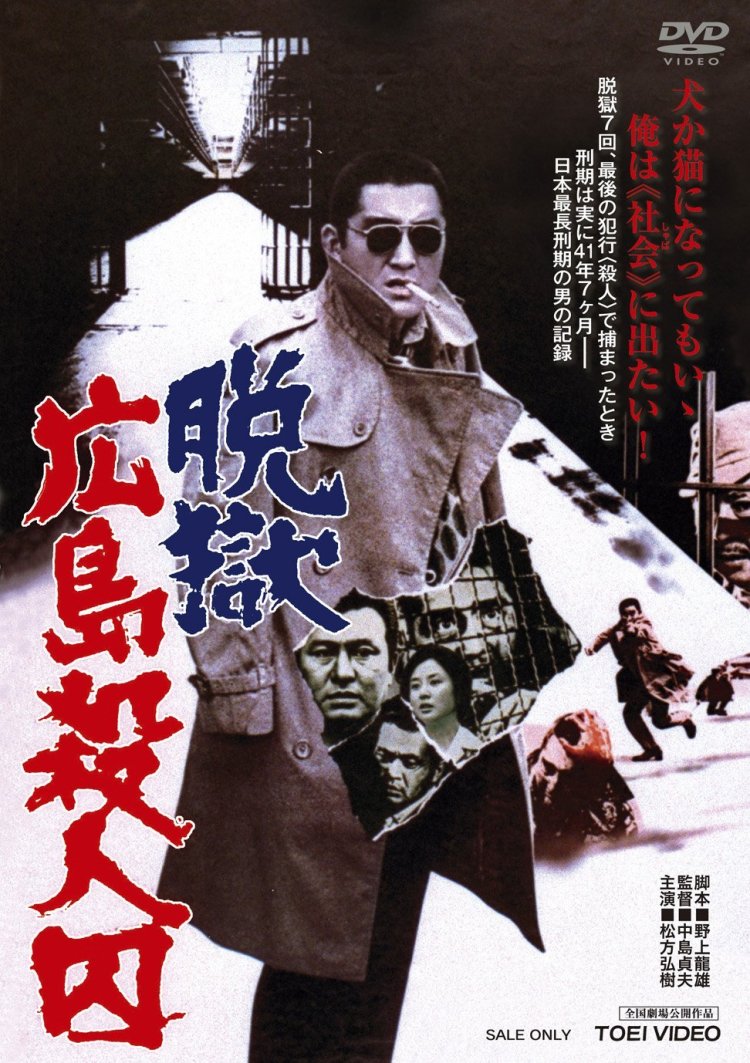

Sadao Nakajima had made his name with Toei’s particular brand of violent action movie, but by the early seventies, the classic yakuza flick was going out of fashion. Datsugoku Hiroshima Satsujinshu (脱獄広島殺人囚, AKA The Rapacious Jailbreaker) follows in the wake of seminal genre buster,

Sadao Nakajima had made his name with Toei’s particular brand of violent action movie, but by the early seventies, the classic yakuza flick was going out of fashion. Datsugoku Hiroshima Satsujinshu (脱獄広島殺人囚, AKA The Rapacious Jailbreaker) follows in the wake of seminal genre buster,

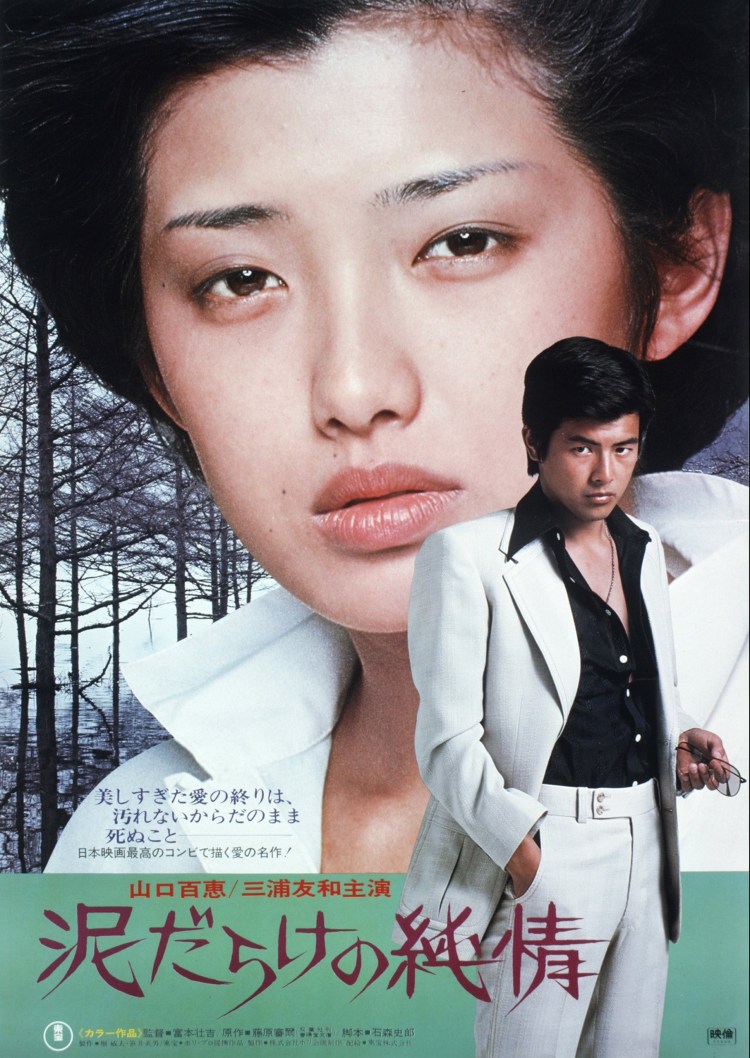

Kiju (Yoshishige) Yoshida is best remembered for his extraordinary run of avant-garde masterpieces in the late 1960s and early 1970s, but even he had to cut his teeth on Shochiku’s speciality genre – the romantic melodrama. Adapted from a best selling novel, Akitsu Springs (秋津温泉, Akitsu Onsen) is hardly an original tale in its doom laden reflection of the hopelessness and inertia of the post-war world as depicted in the frustrated love story of a self sacrificing woman and self destructive man, but Yoshida elevates the material through his characteristically beautiful compositions and full use of the particularly lush colour palate.

Kiju (Yoshishige) Yoshida is best remembered for his extraordinary run of avant-garde masterpieces in the late 1960s and early 1970s, but even he had to cut his teeth on Shochiku’s speciality genre – the romantic melodrama. Adapted from a best selling novel, Akitsu Springs (秋津温泉, Akitsu Onsen) is hardly an original tale in its doom laden reflection of the hopelessness and inertia of the post-war world as depicted in the frustrated love story of a self sacrificing woman and self destructive man, but Yoshida elevates the material through his characteristically beautiful compositions and full use of the particularly lush colour palate. Like most directors of his era, Shohei Imamura began his career in the studio system as a trainee with Shochiku where he also worked as an AD to Yasujiro Ozu on some of his most well known pictures. Ozu’s approach, however, could not be further from Imamura’s in its insistence on order and precision. Finding much more in common with another Shochiku director, Yuzo Kawashima, well known for working class satires, Imamura jumped ship to the newly reformed Nikkatsu where he continued his training until helming his first three pictures in 1958 (Stolen Desire, Nishiginza Station, and Endless Desire). My Second Brother (にあんちゃん, Nianchan), which he directed in 1959, was, like the previous three films, a studio assignment rather than a personal project but is nevertheless an interesting one as it united many of Imamura’s subsequent ongoing concerns.

Like most directors of his era, Shohei Imamura began his career in the studio system as a trainee with Shochiku where he also worked as an AD to Yasujiro Ozu on some of his most well known pictures. Ozu’s approach, however, could not be further from Imamura’s in its insistence on order and precision. Finding much more in common with another Shochiku director, Yuzo Kawashima, well known for working class satires, Imamura jumped ship to the newly reformed Nikkatsu where he continued his training until helming his first three pictures in 1958 (Stolen Desire, Nishiginza Station, and Endless Desire). My Second Brother (にあんちゃん, Nianchan), which he directed in 1959, was, like the previous three films, a studio assignment rather than a personal project but is nevertheless an interesting one as it united many of Imamura’s subsequent ongoing concerns. The Peony Lantern (牡丹燈籠, Kaidan Botan Doro) has gone by many different names in its English version – The Bride from Hades, The Haunted Lantern, Ghost Beauty, and My Bride is a Ghost among various others, but whatever the title of the tale it remains one of the best known ghost stories of Japan. Originally inspired by a Chinese legend, the story was adapted and included in a popular Edo era collection of supernatural tales, Otogi Boko (Hand Puppets), removing much of the original Buddhist morality tale in the process. In the late 19th century, the Peony Lantern also became one of the earliest standard rakugo texts and was then collected and translated by Lafcadio Hearn though he drew his inspiration from a popular kabuki version. As is often the case, it is Hearn’s version which has become the most common.

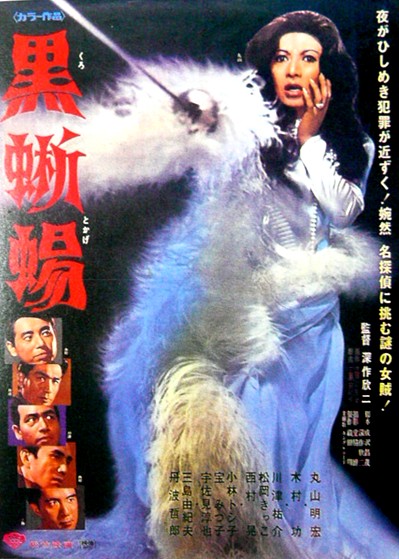

The Peony Lantern (牡丹燈籠, Kaidan Botan Doro) has gone by many different names in its English version – The Bride from Hades, The Haunted Lantern, Ghost Beauty, and My Bride is a Ghost among various others, but whatever the title of the tale it remains one of the best known ghost stories of Japan. Originally inspired by a Chinese legend, the story was adapted and included in a popular Edo era collection of supernatural tales, Otogi Boko (Hand Puppets), removing much of the original Buddhist morality tale in the process. In the late 19th century, the Peony Lantern also became one of the earliest standard rakugo texts and was then collected and translated by Lafcadio Hearn though he drew his inspiration from a popular kabuki version. As is often the case, it is Hearn’s version which has become the most common. Those who only know Kinji Fukasaku for his gangster epics are in for quite a shock when they sit down to watch Black Rose Mansion (黒薔薇の館, Kuro Bara no Yakata). A European inflected, camp noir gothic melodrama, Black Rose Mansion couldn’t be further from the director’s later worlds of lowlife crime and post-war inequality. This time the basis for the story is provided by Yukio Mishima, a conflicted Japanese novelist, artist and activist who may now be remembered more for the way he died than the work he created, which goes someway to explaining the film’s Art Nouveau decadence. Strange, camp and oddly fascinating Black Rose Mansion proves an enjoyably unpredictable effort from its versatile director.

Those who only know Kinji Fukasaku for his gangster epics are in for quite a shock when they sit down to watch Black Rose Mansion (黒薔薇の館, Kuro Bara no Yakata). A European inflected, camp noir gothic melodrama, Black Rose Mansion couldn’t be further from the director’s later worlds of lowlife crime and post-war inequality. This time the basis for the story is provided by Yukio Mishima, a conflicted Japanese novelist, artist and activist who may now be remembered more for the way he died than the work he created, which goes someway to explaining the film’s Art Nouveau decadence. Strange, camp and oddly fascinating Black Rose Mansion proves an enjoyably unpredictable effort from its versatile director.