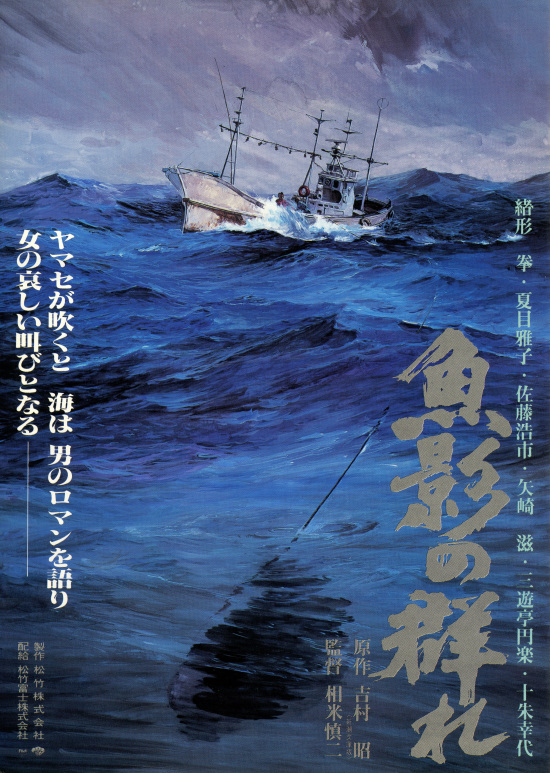

Some men become their work, the quest for success consumes them to the extent that there is barely anything left other than the chase. The Catch (魚影の群れ, Gyoei no Mure), Shinji Somai’s 1983 opus of fishermen at home on the waves and at sea on land is a complex examination of masculinity but also of fatherhood in a rapidly declining world filled with arcane ritual and ancient thought.

Fusajiro (Ken Ogata) is a middle aged man who looks old for his years. Man and boy he’s spent his life at sea, hunting down the elusive tuna fish which can be sold for vast amounts of money in the rare event that one is actually caught. This “first summer” as the title card refers to it, marks a change in his life as the daughter he’s been raising alone since his wife left him many years ago, Tokiko (Masako Natsume), has found a man she wants to marry. Her boyfriend, Shunichi (Koichi Sato), owns a coffee shop in town and Fusajiro has his doubts about a city boy marrying into a fisherman’s family. However, Shunichi isn’t just interested in Tokiko, he wants to set sail too. Though originally reluctant, Fusajiro eventually agrees to take Shunichi as a kind of apprentice but is dismayed when he gets seasick and seems to have no hint of a fisherman’s instinct.

Fusajiro is a legend among his peers – a big man of the sea, a true sailor and top hunter. He’s the one people turn to whenever anything goes wrong on the waves. However, he’s also a gruff man who speaks little and seems to prefer his own company. In the rare event that he is speaking, it’s generally about tuna. When Shunichi first meets Fusajiro he remarks that he knew it must be him because he “smells of the sea”.

A later scene sees Fusajiro catch sight of a woman caught in the rain who immediately starts running away from him. Chasing her just like one of his ever elusive tuna he eventually pins the woman down and takes her back to his boat to complete his conquest. The woman turns out to be his ex-wife, who left him precisely because of this violent behaviour. After momentarily considering returning to him, she realises that he hasn’t changed and accuses him of being unable to distinguish people from fish – he hooks them, reels them in, and if they don’t come willingly he hits them until they do so he can keep them with him. This overriding obsession with domination also costs Fusajiro his daughter when Shunichi is gravely injured on the boat and Fusajiro delays returning to port until he’s secured the tuna he was chasing at the time. Shunichi’s blood and the fish’s mingle together on the deck, one indistinguishable from the other, both victims of Fusajiro’s need to reign supreme over man and fish alike.

Fusajiro tried to warn Tokiko not to marry a fisherman, it would only make her miserable. Shunichi is warned that a fisherman’s life is a difficult one and the seas in this area less forgiving than most, but his mind is made up. Finally acquiring his own boat after selling his cafe, Shunichi, just like Fusajiro, starts to fall under the fisherman’s curse – endlessly chasing, living only for the catch. Unlike Fusajiro, however, Shunichi has little instinct for life at sea and fails to bring home his prey. Little by little, the mounting failures eat away at his self esteem as he feels belittled and humiliated in front of the other sailors culminating in an attempt to reinforce his manhood by raping his own wife. These men are little better than animals, consumed by conquest, permanently chasing at sea and on land. To be defeated, is to be destroyed.

Somai never shies away from the grimness and brutality of the work at hand. Ogata catches and spears these magnificent fish for real and the unfortunate creatures are then carved up right on the dockside before our very eyes. As we’re constantly reminded, physical strength is what matters for a fisherman and Fusajiro is a strong man, duelling with the tuna fish and straining to hold the line with all his might. Yet he’s getting old, his body is failing and like an aged toreador in the ring, his victory is no longer assured. The Japanese title of the film which translates as crowds of shadows of solitary fish expresses his nature more clearly, his fate and the tuna’s are the same – a lonely battle to the death. Unable to forge real human connections on land Fusajiro and his ilk are doomed to live out their days alone upon the sea wreaking only misery for those left behind on the shore.

Original trailer (No subtitles, graphic scenes of animal cruelty)

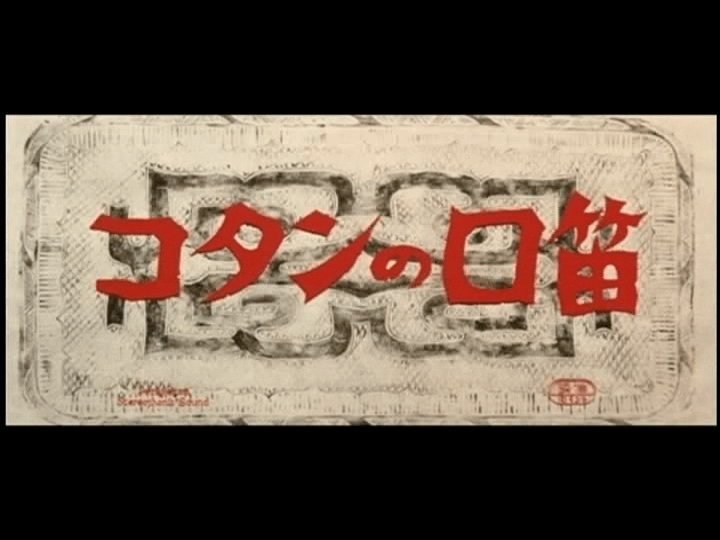

The Ainu have not been a frequent feature of Japanese filmmaking though they have made sporadic appearances. Adapted from a novel by Nobuo Ishimori, Whistling in Kotan (コタンの口笛, Kotan no Kuchibue, AKA Whistle in My Heart) provides ample material for the generally bleak Naruse who manages to mine its melodramatic set up for all of its heartrending tragedy. Rather than his usual female focus, Naruse tells the story of two resilient Ainu siblings facing not only social discrimination and mistreatment but also a series of personal misfortunes.

The Ainu have not been a frequent feature of Japanese filmmaking though they have made sporadic appearances. Adapted from a novel by Nobuo Ishimori, Whistling in Kotan (コタンの口笛, Kotan no Kuchibue, AKA Whistle in My Heart) provides ample material for the generally bleak Naruse who manages to mine its melodramatic set up for all of its heartrending tragedy. Rather than his usual female focus, Naruse tells the story of two resilient Ainu siblings facing not only social discrimination and mistreatment but also a series of personal misfortunes. When a crime has been committed, it’s important to remember that there may be secondary victims whose lives will be destroyed even if they themselves had no direct involvement in the case itself. This is even more true in the tragic case that person who is responsible is themselves a child with parents and siblings still intent on looking forward to a life that their son or daughter will now never lead. This isn’t to place them on the same level as bereaved relatives, but simply to point out the killer’s family have also lost a child who they have every right to grieve for, though their grief will also be tinged with guilt and shame.

When a crime has been committed, it’s important to remember that there may be secondary victims whose lives will be destroyed even if they themselves had no direct involvement in the case itself. This is even more true in the tragic case that person who is responsible is themselves a child with parents and siblings still intent on looking forward to a life that their son or daughter will now never lead. This isn’t to place them on the same level as bereaved relatives, but simply to point out the killer’s family have also lost a child who they have every right to grieve for, though their grief will also be tinged with guilt and shame. Cyberpunk, for many people, is a movement which came to define the 1980s and continues to enjoy various kinds of resurgences and rebirths even into the new century. Beginning the the ‘60s and ’70s in dystopian science fiction afraid of the impact of advancing technologies in society, it’s not surprising that the genre began to actively embrace influences from the East and especially that of the more technologically advanced and economically superior Japan. However, when Japan made its own cyberunk cinema, the “punk” element is the one that’s important. These movies sprang from the punk music scene and often star punk bands and musicians as well as featuring high energy punk rock inspired scores.

Cyberpunk, for many people, is a movement which came to define the 1980s and continues to enjoy various kinds of resurgences and rebirths even into the new century. Beginning the the ‘60s and ’70s in dystopian science fiction afraid of the impact of advancing technologies in society, it’s not surprising that the genre began to actively embrace influences from the East and especially that of the more technologically advanced and economically superior Japan. However, when Japan made its own cyberunk cinema, the “punk” element is the one that’s important. These movies sprang from the punk music scene and often star punk bands and musicians as well as featuring high energy punk rock inspired scores. If there’s one thing you can say about the work of Japan’s great comedy master Koki Mitani, it’s that he knows his cinema. Nowhere is the abundant love of classic cinema tropes more apparent than in 2008’s The Magic Hour (ザ・マジックアワー) which takes the form of an absurdist meta comedy mixing everything from American ‘20s gangster flicks to film noir and screwball comedy to create the ultimate homage to the golden age of the silver screen.

If there’s one thing you can say about the work of Japan’s great comedy master Koki Mitani, it’s that he knows his cinema. Nowhere is the abundant love of classic cinema tropes more apparent than in 2008’s The Magic Hour (ザ・マジックアワー) which takes the form of an absurdist meta comedy mixing everything from American ‘20s gangster flicks to film noir and screwball comedy to create the ultimate homage to the golden age of the silver screen.