According to the driver aboard the bus at the centre of Hiroshi Shimizu’s Tomorrow There Will Be Fine Weather (明日は日本晴れ, Asu wa Nipponbare), “that ridiculous war ruined everything”. Shimizu had directed a similar film in 1936, Mr Thank You, in which times had been hard for all but people tried to stay cheerful and help where they could. But here, by contrast, the atmosphere is much less jovial. Everyone is fed up, unhappy, dissatisfied, and irritated far beyond the inconvenience of being delayed on their journey.

Once again shot on location, the film follows a bus on the outskirts of Kyoto making the journey along a mountain pass from the city to an onsen town before breaking down half way. It’s several miles across difficult mountainous terrain to the nearest town in either direction and many people aboard the bus are elderly or have disabilities that make simply walking the rest of the way a difficult prospect while no one can really say when help will come because they’re dependent on the arrival of the following service or some other form of transport that could get a message out for a mechanic or replacement bus.

In any case, just as in Mr Thank You there is a diverse contingent aboard each of whom have particular reasons for travelling and for being upset about the delay. A trio of men begin by complaining that this journey which once took two hours now takes three while the bus itself has become worn down and unreliable. Even so, the fares are now much more expensive. What’s most surprising is that the men loudly and openly discuss their occupation as black market traders while simultaneously complaining about an increased police presence interfering with their work. An irritated, besuited man sitting across the aisle is the only one to challenge them, asking if they pay taxes on their clearly illegal earnings to which the answer is obvious though the men mostly complain about how it wouldn’t be worth their while if they did rather than outright denying a responsibility to pay. The man tells them that they’re part of the problem and that the future of the country is assured only if people pay their taxes, with which the men otherwise seem to agree. When the bus breaks down, one of them is most worried that his late arrival will cause concern for his wife who may assume he’s been caught and arrested.

But there’s a small drama playing out in the front of the bus too as the conductress gossips with the driver certain that the beautiful woman sitting half-way back is a well-known Tokyo dancer, Waka, who she’s heard is on her way to bury the ashes of her child seemingly born out of wedlock. The driver, Sei, grimaces slightly as if he didn’t want to have this conversation and as we later discover once knew Waka long ago before the war which has changed each of them. A blind man, Fuku, now working as a masseur after losing his sight in the war, once knew them both hatches a plan to try and get them to patch things up. But as Sei later says, they’ve both been through far too much and are no longer the same people. Nothing can be as it was before, but in a way that’s alright. There is still hope for the future on the broken bus that is post-war Japan if only someone can figure out how to get the engine going again.

Nevertheless, the scars from this war are still very noticeable. One of the black-marketers has a missing leg and later lays into an old man who confesses that he was a military commander, hounding him for his responsibility for the folly of the war which men like him forced them to continue long after it was obvious that it was lost. Fuku is much more sanguine and after a minor misunderstanding able to find a way to communicate with an elderly man who is deaf despite the incompatibility of their disabilities as they help each other board the replacement bus to the new Japan. Sei, and the slightly younger conductress who is not so secretly in love with him, meanwhile remain stuck on the broken bus symbolically unable to move forward no matter how much Sei insists it’s time to “get over the war” and that he just wants to forget the past and start living again. Perhaps it’s for men like him who seem fine on the surface that the scars run deepest, overburdened by all that this “ridiculous war” took from them in unlived futures and broken dreams. Meanwhile Shimizu follows the other bus onward along the precarious and winding mountain roads hoping for better weather in the hot springs town ahead.

Tomorrow There Will Be Fine Weather screens at Japan Society New York on May 17 as part of Hiroshi Shimizu Part 2: The Postwar and Independent Years.

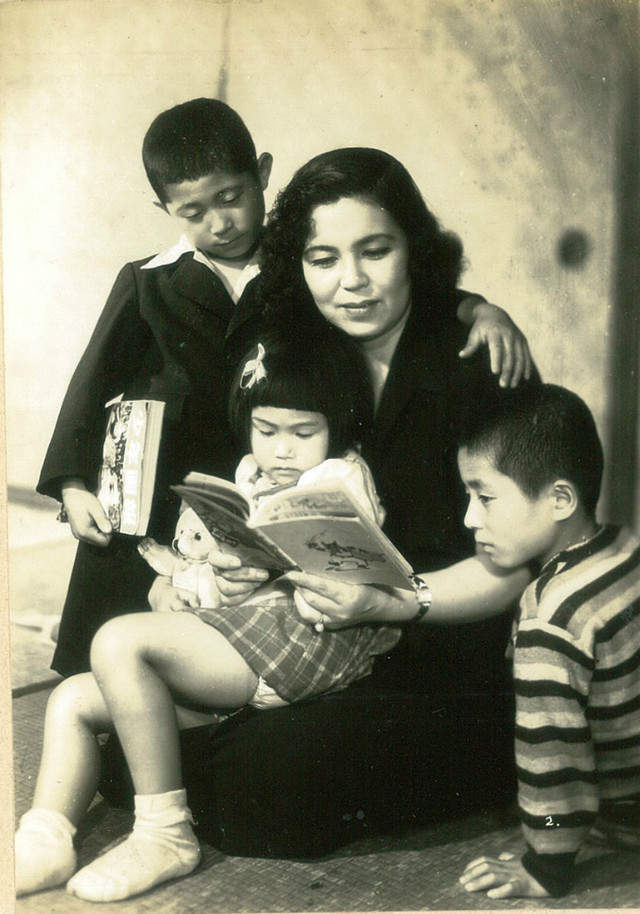

Shimizu’s depression era work was not lacking in down on their luck single mothers forced into difficult positions as they fiercely fought for their children’s future, but 1950’s A Mother’s Love (母情, Bojo) takes an entirely different approach to the problem. Once again Shimizu displays his customary sympathy for all but this particular mother, Toshiko, does not immediately seem to be the self sacrificing embodiment of maternal virtues that the genre usually favours.

Shimizu’s depression era work was not lacking in down on their luck single mothers forced into difficult positions as they fiercely fought for their children’s future, but 1950’s A Mother’s Love (母情, Bojo) takes an entirely different approach to the problem. Once again Shimizu displays his customary sympathy for all but this particular mother, Toshiko, does not immediately seem to be the self sacrificing embodiment of maternal virtues that the genre usually favours.