Led by Lee Myung-se, The Killers (더 킬러스) was originally billed as a six-part anthology film featuring different takes on the short story by Ernest Hemingway, but somewhere along the way took a kind of detour and now arrives as a four partner with a looser theme revolving around noir and crime cinema. Frequently referencing the Edward Hopper painting Nighthawks, the film hints at urban loneliness and a haunting sense of futility along with the mythic quality of noir as a tale that tells itself.

At least that’s in part how it is for unreliable the narrator of the first episode, a petty gangster who wakes up in a mysterious bar after being cornered by rival thugs. While in there he meets a similarly lost, middle-aged film director in the middle of a strange date with a fawning young woman who’ve definitely wandered into the wrong place. A sense absurdity is echoed in the fact that the man continues to sit in the bar oblivious to the knife in his back until the bar lady pulls it out for him and exposes the real reason why she lures lonely souls to this strange place out of time. Even so, thanks to her dark initiation the gangster is able to become himself and stand up against the rival thugs who were bullying him with his newfound “feistiness” having overcome something of the futility of black and white, classic noir opening sequence.

That’s something that never really happens for the heroes of part two who are a trio of youngsters trapped in Hell Joseon unable to escape their lives as cut price contract killers working below minimum wage for a chaotic company in which everything has been sub-contracted into oblivion. Ironically, one had dreams of becoming a policeman and another a nun while the third has recently had plastic surgery in the hope of landing an acting gig and claims he’s not in this for the money but to make the world a better place. Seeing their work as a public service, they tell each other that it’s wrong to grumble over their unfair pay because other people get less and are otherwise incapable of standing up for themselves until they take a leaf out of the boss’ book and try a subcontracting of their own which doesn’t quite go to plan.

While the first two episodes had been set in the present day the second two are set during the long years of dictatorship, the first sometime in the 1960s under the rule of President Park as an undercover detective and two men who appear to be unsubtle KCIA agents descend on a noirish, rundown bar with a picture of Nighthawks on the wall waiting for a mysterious fugitive to arrive. They don’t appear to know anything about why their target needs to be caught or who he is save for a daffodil tattoo on his arm and are merely they shady figures of authoritarian power we can infer are hot on the tracks of someone hostile to the regime. In any case, they are they are about to have the tables turned on them in a demonstration of their inefficacy in their power.

It’s the fourth and final piece unmistakably directed by Lee himself, however, that brings the themes to the four as it opens with an allusion to the assassination of President Park as the narrator tells us that it is 1979 and someone sent a bullet into the heart of darkness but the darkness did not die. The two goons who later show up are KCIA thugs working for the new king Chun Doo-hwan come to threaten the denizens of the cafe which include a man called “Smile” because he can’t and a woman called “Voice” because she has none while trapped inside an authoritarian regime. Inhabitants of Diaspora City, a home to the exiled, they have only a small hole to another world which affords them the ability to dream. Relentlessly surreal the segment is marked by Lee’s characteristic visual flair and sense of noirish melancholy that extends all the way out to a world more recognisably our own though no less lonely or oppressive.

The Killers screened as part of this year’s New York Asian Film Festival.

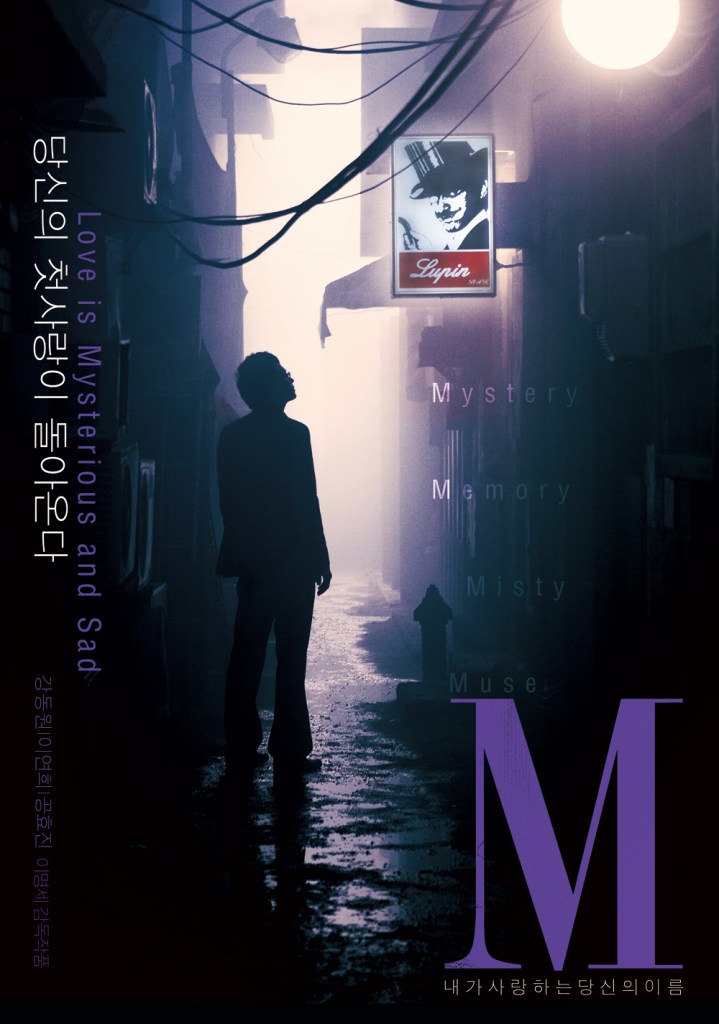

“More specific, less poetic” the distressed author hero of Lee Myung-se’s M (엠) repeatedly types after a difficult conversation with his editor. Almost a meta comment on Lee’s process, it’s just as well that it’s advice he didn’t take – M is a noir poem, a metaphor for an artist’s torture, and a living ghost story in which a man shifts between worlds of memory, haunted and hunted by unidentifiable pain. Reality, dream, and madness mingle and merge as a single kernel of confusion causes widespread panic in a desperate writer’s already strained mind.

“More specific, less poetic” the distressed author hero of Lee Myung-se’s M (엠) repeatedly types after a difficult conversation with his editor. Almost a meta comment on Lee’s process, it’s just as well that it’s advice he didn’t take – M is a noir poem, a metaphor for an artist’s torture, and a living ghost story in which a man shifts between worlds of memory, haunted and hunted by unidentifiable pain. Reality, dream, and madness mingle and merge as a single kernel of confusion causes widespread panic in a desperate writer’s already strained mind.