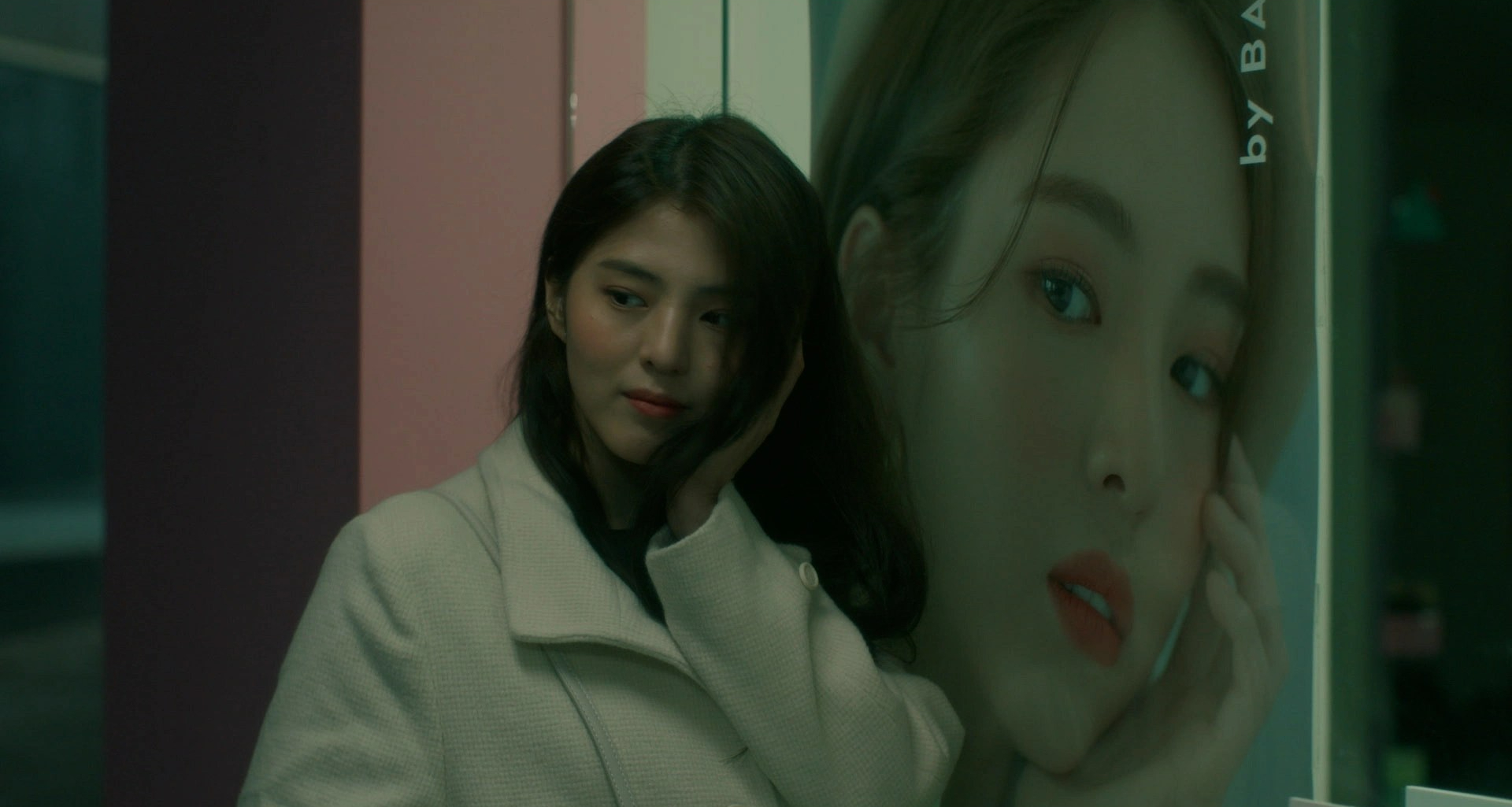

The unnamed mother (Oh Min-ae) at the centre of Lee Mi-rang’s Concerning My Daughter (딸에 대하여) has only one wish, that her daughter will find a nice man to marry and have a few grandchildren. But Green (Im Se-mi) is gay and has been in a relationship with her partner Rain (Ha Yoon-kyung) for the last seven years though her mother doesn’t seem to accept that what they have together is “real” believing it to be some kind of delusion that’s holding Green back from her happy maternal future.

When she suggests Green move back in with her after her attempt to secure a loan to help her out with the rising cost of housing is denied, it doesn’t seem to have occurred to her that Rain would be coming too while it perhaps seemed so natural to Green that it didn’t occur to spell it out. Green can at times be obtuse and insensitive, unfair both to her mother and to Rain who bears the unpleasant atmosphere with grace and tries her best to get along with her new mother-in-law who is openly hostile towards her and makes no secret of the fact she would prefer her to leave. Of course, some of these issues may be the same were it a heterosexual relationship as the mother-in-law struggles to accept the presence of the new spouse in the family home and the changing dynamics that involves, but Green’s mother’s resentment is so acute precisely because her daughter’s partner is a woman. She cannot understand the nature of their relationship because it will produce no children and to her therefore seems pointless.

While her attitude is in part determined by prejudice and a sense of embarrassment that her daughter is different, it’s the question of children which seems to be foremost in her mind. Another woman of a similar age at her job at a care home remarks on her maternal success having raised her daughter to become a professor, but she also says that only by leaving children and grandchildren behind you can die with honour. Green’s mother is the primary carer for an elderly lady, Mrs Lee (Heo Jin), who had no children of her own though sponsored several orphans none of whom appear to have remained in touch with her. Now ironically orphaned herself in her old age, Green’s mother is the only one who cares for her while the manager berates her for using too many resources and eventually degrades Mrs Lee’s access to care Green’s mother suspects precisely because she has no family and therefore no one to advocate for her.

It’s this fate that she fears for her daughter, that without biological children she will become a kind of non-person whose existence is rendered meaningless. Of course, it’s also a fear that she has for herself and her tenderness towards Mrs Lee is also a salve for her own loneliness and increasing awareness of mortality. Green is her only child, and she may also fear that she will not want to look after her as she might traditionally be expected to because her life is so much more modern as exemplified by the bread and pasta the girls bring into her otherwise fairly traditional Korean-style home. On some level she is probably aware that if she continues to pressure Green to accept a traditional marriage they may end up becoming estranged and she will be in the same position as Mrs Lee, wilfully misused by a cost-cutting care industry because they know there’s no one to kick up a fuss about her standard of care.

Even so, it doesn’t seem to occur to her that Rain could care for her daughter into their old age. Resentfully asking her why they “have to” to live together, Rain patiently explains that in a society which rejects their existence, in which they are unable to marry or adopt children, togetherness is all that they have. Green is currently engaged in a battle with her institution which has fired her colleague on spurious grounds but really because of her sexuality with claims that some students are “uncomfortable” with her classes. The violence with which the women are attacked is emblematic of that they endure from their society while even colleagues interviewing her invalidate Green’s concerns because she too is “one of them,” in their prejudicial way of speaking.

Green’s mother had also, rather oddly, said that her daughter wasn’t like that when Rain reluctantly explained her difficulties at work and again resents that she’s making waves rather than keeping her head down and getting on with her career. Her decision to jump in a car with boxes of biscuits intending to smooth things over with Green’s boss by apologising on her behalf bares out her old-fashioned attitudes, though she too is shocked by the violence directed at Green and her colleague. When her lodgers ask about Rain, she tells them she’s her daughter’s friend, while she avoids the question when her colleagues ask, still embarrassed that her daughter has not followed the conventional path as if it reflected badly on her parenting.

Yet through her experiences with Mrs Lee and Rain’s constant, caring patience she perhaps comes to understand that her daughter won’t be alone when she’s old and that she too does not need to be so lonely now. There’s something a little a sad in the various ways Green’s mother is told that her attachment to Mrs Lee is somehow inappropriate as if taking an interest in the lives of those not related to us by blood were taboo even if it’s also sadly true that it’s also in Mrs Lee’s best interests to ask those questions to protect her from those who might not have her best interests at heart. What the film seems to say in the end is that we should all take better care of each other, something which Green’s mother too may come to realise in coming to a gradual, belated acceptance of her daughter-in-law if in part through recognising that they aren’t alone and that it’s a blessing that her daughter is loved and will be cared for until the end of her days.

Concerning My Daughter screened as part of this year’s London Korean Film Festival.

Trailer (English subtitles)