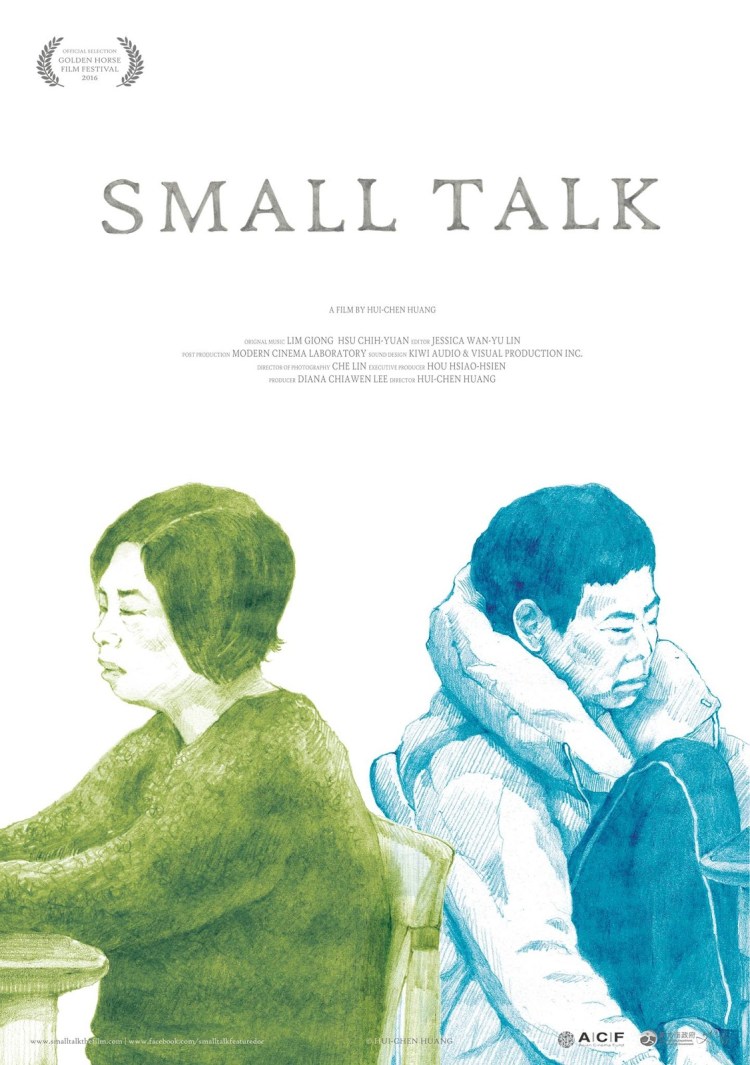

“Who would want to understand me?” asks the laconic mother of filmmaker Huang Hui-Chen early in her autobiographical documentary, Small Talk (日常對話, Rì Cháng Duì Huà). “We do” the director replies, “but you won’t let us”. Huang’s film is, in a sense, an attempt to break through an emotional fourth wall in order to make sense of her complicated relationship with her distant mother Anu if only to ensure that her own daughter never feels as rejected or isolated as she herself has done living under the same roof with a woman she cannot quite claim to know.

“Who would want to understand me?” asks the laconic mother of filmmaker Huang Hui-Chen early in her autobiographical documentary, Small Talk (日常對話, Rì Cháng Duì Huà). “We do” the director replies, “but you won’t let us”. Huang’s film is, in a sense, an attempt to break through an emotional fourth wall in order to make sense of her complicated relationship with her distant mother Anu if only to ensure that her own daughter never feels as rejected or isolated as she herself has done living under the same roof with a woman she cannot quite claim to know.

In fact, Huang’s childhood memories of her mother are mainly to do with her absence. Even her younger sister eventually remarks that she always felt as if her mother was uncomfortable at home, preferring to spend time out with her friends rather than with her children. Forced to join her mother in her Spirit Guide business rather than attend school like the other kids, Huang began to resent her but also longed to be close to Anu despite her continuing distance. This desire for closeness is, ironically, only achieved through the introduction of the camera, acting as an impartial witness somehow uniting the two and making it possible to say the things which could not be said and ask the questions which could not be asked.

For Huang, the central enigma of her mother’s life is why she married man and had two daughters if she always knew she was gay. That her mother is a lesbian is something Huang always seemed to just know – it’s not as if Anu ever sat her down and explained anything to her, she gradually inferred seeing as her mother had frequent female partners and seemed to prefer spending time with groups of other women. Putting the question to her extended family perhaps begins to illuminate part of an answer. Like Anu, they will not speak of it. They claim not to know, that they do not want to know, and that they would rather change the subject. Even Anu, who otherwise seems to have no interest in hiding her sexuality, remarks that it “isn’t a good thing to talk about”. Nevertheless, her marriage seems not to have been a matter of choice. In those days marriages were arranged by the family, which is perhaps how she ended up with a man her sister describes as “no good” who later became a tyrannical, violent drunk she eventually had to flee from and go into hiding with her two young daughters.

Abusive marriages become a melancholy theme as Anu briefly opens up to recall throwing away sleeping pills her own mother had begun to stockpile in desperation to get away from her violent husband. A former girlfriend also mentions having divorced her husband because he was abusive, but seems surprised to learn that Anu had been a victim too. According to her, Anu had told her she was married once but only for a week and that her two children were “adopted”. Of course, this is mildly upsetting for Huang to hear, but seems to amuse her in discovering her mother’s tendency to spin a different yarn to each of her lovers to explain the existence of her family while also distancing herself from it. This seems to be the key that eventually unlocks something of Anu’s aloofness. Humiliated by her capitulation to marriage and then by her mistreatment at the hands of her husband, she cannot reconcile the two sides of her life and has chosen, therefore, to reject the idea of herself as a mother. Something she later partially confirms in admitting that though she does not regret her daughters, given the choice she would not marry again, not even if same sex marriages were legal believing herself to be the sort of person best off alone.

Huang interrogates her mother with a rigour that is difficult to watch, often to be met only with silence or for Anu to walk away with one of her trademark “I’m Off”s. It may be true that most people have something they would rather not talk about, and perhaps Anu is entitled to her silence but if no one says anything, then nothing will change and the cycle of love and resentment will continue on in infinity. Using the camera as a shield, Huang brokers some painful, extremely raw truths to her elusive mother and does perhaps achieve a moment of mutual catharsis but is also too compassionate to satisfy for laying blame, exploring the many social ills from entrenched homophobia to persistent misogyny and even the class-based oppression hinted at by the use of native dialect rather than standard Mandarin which help to explain her mother’s complicated sense of identity. Yet she does so precisely as a means of exorcising ghosts more personal than political in the hope that her own daughter will grow up to know that she is loved, unburdened by a legacy of violence and shame, and free to live her life in whichever way she chooses.

Small Talk was screened as part of the Taiwan Film Festival UK 2019.

Original trailer (English subtitles)

When you feel you’ve discharged all your social obligations, you might feel as if you’ve a right to live by your own desires. Whether the dreams you abandoned in youth will still be there waiting for you is, however, something of which you can be far less certain. Following the death of her husband, one Filipina grandma decides to find out, taking to the road with her best friend who is, incidentally, wanted for murder and carrying around the severed head of her late spouse in a Louis Vuitton handbag belonging to her vacuous step-daughter, in search of the one that got away.

When you feel you’ve discharged all your social obligations, you might feel as if you’ve a right to live by your own desires. Whether the dreams you abandoned in youth will still be there waiting for you is, however, something of which you can be far less certain. Following the death of her husband, one Filipina grandma decides to find out, taking to the road with her best friend who is, incidentally, wanted for murder and carrying around the severed head of her late spouse in a Louis Vuitton handbag belonging to her vacuous step-daughter, in search of the one that got away.

Some situations are destined to end in tears. Kaze Shindo’s Love Juice adopts the popular theme of unrequited love but complicates it with the peculiar circumstances of Tokyo at the turn of the century which requires two young women to be not just housemates but bedmates and workmates too. One is straight, one is gay and in love with her friend who seems to get off on manipulating her emotions and is overly dependent on her more responsible approach to life, but both are trapped in a low rent world of grungy nightclubs and sleazy hostess bars.

Some situations are destined to end in tears. Kaze Shindo’s Love Juice adopts the popular theme of unrequited love but complicates it with the peculiar circumstances of Tokyo at the turn of the century which requires two young women to be not just housemates but bedmates and workmates too. One is straight, one is gay and in love with her friend who seems to get off on manipulating her emotions and is overly dependent on her more responsible approach to life, but both are trapped in a low rent world of grungy nightclubs and sleazy hostess bars. In

In