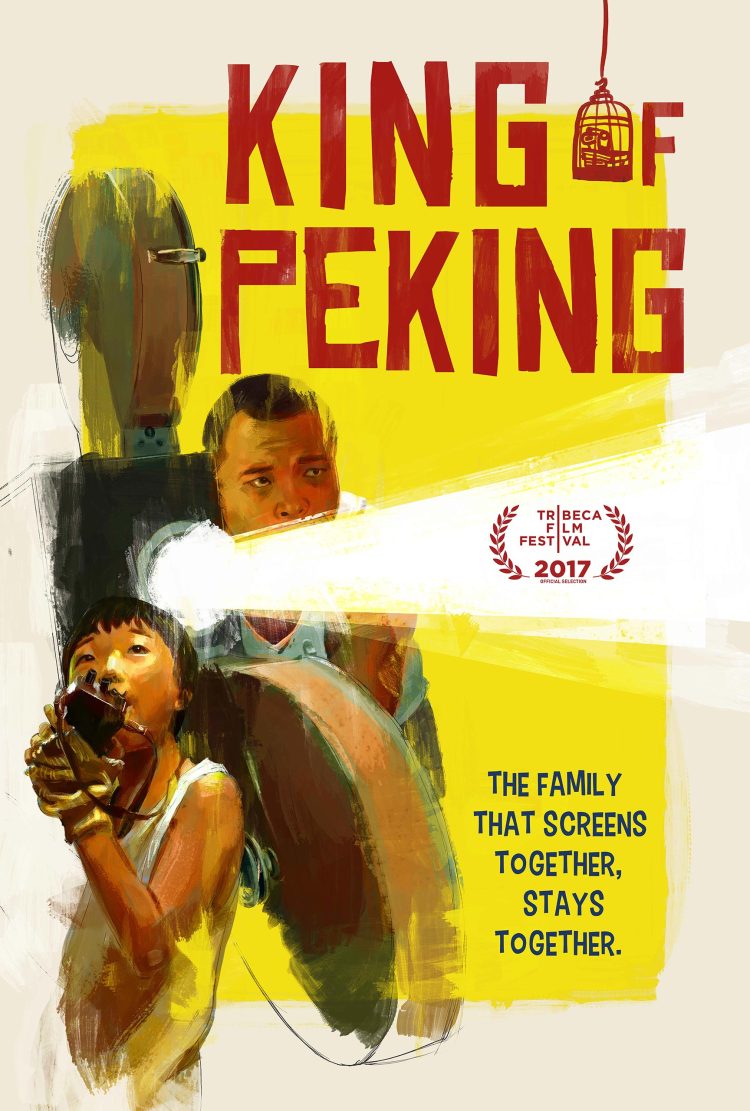

Listen up, kids. Things were very different in the ‘90s when the internet didn’t really exist and people still queued round the block to get into giant single screen cinemas. Sam Voutas’ second film, King of Peking (京城之王, Jīngchéng Zhī Wáng), is an homage to these more innocent times taking place in a small corner of Beijing where a divorced father and his son are a charming double act of itinerant projectionists screening “Hollywood movies” for a dollar in the town square. Big Wong and Little Wong see themselves as “movie people” but their days are definitely numbered.

Listen up, kids. Things were very different in the ‘90s when the internet didn’t really exist and people still queued round the block to get into giant single screen cinemas. Sam Voutas’ second film, King of Peking (京城之王, Jīngchéng Zhī Wáng), is an homage to these more innocent times taking place in a small corner of Beijing where a divorced father and his son are a charming double act of itinerant projectionists screening “Hollywood movies” for a dollar in the town square. Big Wong and Little Wong see themselves as “movie people” but their days are definitely numbered.

Big Wong (Jun Zhao) owns a Soviet era projector and a few reels of not quite recent but not yet classic movies. While Big Wong sets up a giant sheet and readies the reels, Little Wong runs round town “advertising” the event by shouting as loud as he can. The duo get a fair amount of customers but, as one loudmouth points out, this movie came out ages ago and he already has a copy on video at home – who wants to pay a dollar to watch it on a sheet in the square? This is also a question Wong’s ex-wife wants to know the answer to when she unceremoniously turns up and lays into Wong for “exploiting” their son. Wong’s wife left the boy behind claiming she couldn’t look after him but has since changed her mind. She wants an unfeasible amount of money or Little Wong. Little Wong wants to stay with his dad. Finding the money seemed a difficult prospect to begin with but when the projector catches fire and they have to give everyone their money back it seems all but impossible.

Voutas’ film is a father son drama in which the pair start off as firm friends – nicknaming each other Riggs and Murtaugh just like the Lethal Weapon heroes. Curiously enough, Lethal Weapon 4 is one of the films playing in the on screen cinema with a hand painted Chinese poster which places Rene Russo centre stage with Gibson and Glover on either side. Somewhat surprisingly, Jet Li does not feature. Sadly their father/son relationship is set to deteriorate ahead of schedule as Big Wong comes up with a plan which is intended to pay off his wife and get her to leave him and Little Wong alone. Taking note of the rude customer’s comments, Big Wong gets an idea, a set of DVD recorders, and a camcorder he can stuff into the penguin shaped bin in the cinema to rip off the latest releases, design covers, and sell them on DVD on street corners. Pretty soon, the Wongs are ruling the streets with dad’s innovative business model and son’s ruthless sales patter.

Of course, all of this is very morally dubious. Little Wong doesn’t quite like it, but is won over by his dad’s enthusiasm and, after all, aren’t they doing it because they love movies and want to share them with more people? Well, kind of, but it’s mostly for the money and Big Wong’s scheming soon works against him. Unlike his dad, Little Wong’s great love is for volcanoes, and Big Wong said he’d help him build one but he’s always too busy with the “business”. In becoming successful in his plan, Big Wong has forgotten why he started it in the first place and is too slow to see how his moral laxity is affecting the development of his son’s character.

Voutas avoids a neatly happy ending, going for something more realistic but also heartwarming in its own way as father and son end up understanding each other a little better but remain conscious of the growing distance between them. A tribute to ‘90s Chinese cinema with its oversaturated colour schemes, makeshift production budgets and essential red curtain opening, King of Peking is a warmhearted nostalgia trip filled with strange characters somehow left behind by China’s increasing modernisation such as the very young security guard at the cinema who talks about “work units” being a family and barks at his ushers as if they were a revolutionary cadre about to head off into battle. The security guard, officiously checking tickets, asks one customer for his “purpose of visit” to which he replies “for enjoyment and to forget all my poor life choices”. Big Wong has made a few poor life choices of his own and not all of them can be repaired through the magic of cinema, but as King of Peking proves the movie may soon be over but the memories last a lifetime.

Screened at the BFI London Film Festival 2017.

Original trailer (English subtitles)

The

The  Chinese independent cinema has been in the ascendent recently, becoming a regular presence at high profile festivals. This year’s selection of films from the mainland includes two very different animated features alongside comedy, action and arthouse.

Chinese independent cinema has been in the ascendent recently, becoming a regular presence at high profile festivals. This year’s selection of films from the mainland includes two very different animated features alongside comedy, action and arthouse. Two giants of Hong Kong cinema return – celebrated filmmaker Ann Hui with a tale of love and resistance, and legendary cinematographer Christopher Doyle shooting a noir fairytale for Jenny Suen.

Two giants of Hong Kong cinema return – celebrated filmmaker Ann Hui with a tale of love and resistance, and legendary cinematographer Christopher Doyle shooting a noir fairytale for Jenny Suen. Japanese entries are dominated by animation but there’s also space for Takashi Miike’s manga adaptation Blade of the Immortal which headlines the Thrill section, as well as Naoko Ogigami’s latest Close-Knit, and the recent 4K restoration of 60s avant-garde masterpiece Funeral Parade of Roses.

Japanese entries are dominated by animation but there’s also space for Takashi Miike’s manga adaptation Blade of the Immortal which headlines the Thrill section, as well as Naoko Ogigami’s latest Close-Knit, and the recent 4K restoration of 60s avant-garde masterpiece Funeral Parade of Roses. Everything you’d expect from Korea from anarchic documentary to violent procedural and the annual return of Hong Sang-soo.

Everything you’d expect from Korea from anarchic documentary to violent procedural and the annual return of Hong Sang-soo. Thailand’s two entries feature youth looking forward and age looking back.

Thailand’s two entries feature youth looking forward and age looking back.

First time writer/director Wang Yichun draws on her own experiences for What’s in the Darkness (黑处有什么, Hei chu you shenme), a beautifully shot coming of age piece with serial killer intrigue running in the background. Seen through the eyes of its protagonist, What’s in the Darkness neatly matches the heroine’s journey into adolescence with the changing nature of Chinese society.

First time writer/director Wang Yichun draws on her own experiences for What’s in the Darkness (黑处有什么, Hei chu you shenme), a beautifully shot coming of age piece with serial killer intrigue running in the background. Seen through the eyes of its protagonist, What’s in the Darkness neatly matches the heroine’s journey into adolescence with the changing nature of Chinese society.

Indie animation talent Makoto Shinkai has been making an impact with his beautifully drawn tales of heartbreaking, unresolvable romance for well over a decade and now with Your Name (君の名は, Kimi no Na wa) he’s finally hit the mainstream with an increased budget and distribution from major Japanese studio Toho. Noticeably more upbeat than his previous work, Your Name takes on the star-crossed lovers motif as two teenagers from different worlds come to know each other intimately without ever meeting only to find their youthful romance frustrated by the vagaries of time and fate.

Indie animation talent Makoto Shinkai has been making an impact with his beautifully drawn tales of heartbreaking, unresolvable romance for well over a decade and now with Your Name (君の名は, Kimi no Na wa) he’s finally hit the mainstream with an increased budget and distribution from major Japanese studio Toho. Noticeably more upbeat than his previous work, Your Name takes on the star-crossed lovers motif as two teenagers from different worlds come to know each other intimately without ever meeting only to find their youthful romance frustrated by the vagaries of time and fate. How well do you know your neighbours? Perhaps you have one that seems a little bit strange to you, “creepy”, even. Then again, everyone has their quirks, so you leave things at nodding at your “probably harmless” fellow suburbanites and walking away as quickly as possible. The central couple at the centre of Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s return to genre filmmaking Creepy (クリーピー 偽りの隣人, Creepy Itsuwari no Rinjin), based on the novel by Yutaka Maekawa, may have wished they’d better heeded their initial instincts when it comes to dealing with their decidedly odd new neighbours considering the extremely dark territory they’re about to move in to…

How well do you know your neighbours? Perhaps you have one that seems a little bit strange to you, “creepy”, even. Then again, everyone has their quirks, so you leave things at nodding at your “probably harmless” fellow suburbanites and walking away as quickly as possible. The central couple at the centre of Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s return to genre filmmaking Creepy (クリーピー 偽りの隣人, Creepy Itsuwari no Rinjin), based on the novel by Yutaka Maekawa, may have wished they’d better heeded their initial instincts when it comes to dealing with their decidedly odd new neighbours considering the extremely dark territory they’re about to move in to…

It’s never too late to be what you might have been – a statement attributed to George Eliot which may be as fake as one of the promises offered by the protagonist of Hirokazu Koreeda’s latest attempt to chart the course of his nation through its basic social unit, After the Storm (海よりもまだ深く, Umi yori mo Mada Fukaku). Reuniting Kirin Kiki and Hiroshi Abe as mother and son following their star turns in

It’s never too late to be what you might have been – a statement attributed to George Eliot which may be as fake as one of the promises offered by the protagonist of Hirokazu Koreeda’s latest attempt to chart the course of his nation through its basic social unit, After the Storm (海よりもまだ深く, Umi yori mo Mada Fukaku). Reuniting Kirin Kiki and Hiroshi Abe as mother and son following their star turns in