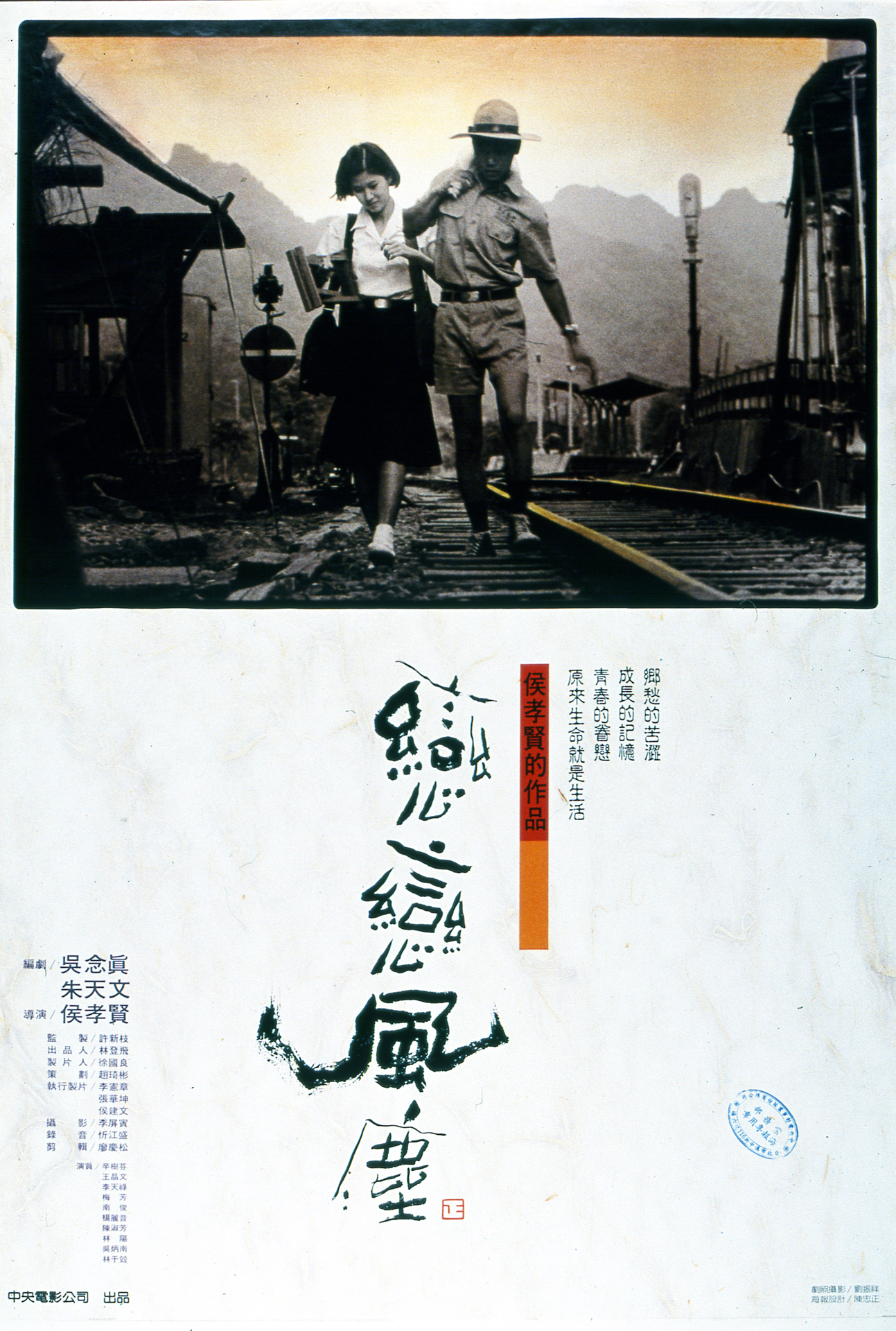

Geographical dislocation and changing times slowly erode the innocent love of a young couple in Hou Hsiao-Hsien’s nostalgic youth drama, Dust in the Wind (戀戀風塵, Liànliàn Fēngchén). Hoping for a better standard of life, they venture to the city but discover that the grass is always greener while their problems largely follow them and the young man finally alienates his childhood love with his stubborn male pride, imbued with a general sense of futility in the inability to better himself because of the constraints of a society which is changing but unevenly and not perhaps in ways which ultimately benefit.

Opening with a long POV shot of a train emerging from darkness into the light, Hou finds Wen (Wang Chien-wen) and Huen (Xin Shufen) travelling home from school she bashfully admitting that she didn’t understand their maths homework while he automatically shoulders the heavy rice bag her mother has asked her to collect on the way. Their relationship is indeed close and intimate, almost like a long-married couple, yet there’s also little that tells us they are romantically involved rather than siblings or merely childhood friends. Given his family’s relative poverty and the lack of opportunities available in the village, Wen decides not to progress to high school but move to Taipei in search of work while studying in the evenings. Some time later Huen joins him, but they evidently struggle to reassume the level of comfort in each other’s company they experienced at home, Wen permanently sullen and resentful while Huen perhaps adapts more quickly to the rhythms of urban life than he expected if also intensely lonely and fearful, no longer confident in his ability and inclination to care for her.

Huen clearly envisions a future for the both of them of conventional domesticity, eventually writing to Wen after he is drafted for his military service that a mutual friend spared the draft because of a workplace injury is moving back to his hometown to get married and is planning to sell off land to build houses one of which will be for them. But Wen is still consumed with resentment, frustrated that he can’t make headway in Taipei and in part blaming Huen for highlighting his failure while also holding her responsible when the motorbike he’d been using for work as a delivery driver is stolen after he gives her a ride to town to buy presents for her family. They only seem to speak through the bars of a small window in the basement tailoring room where Huen works as if something is always between them while she complains of her loneliness, Wen apparently ignoring her for long stretches of time while studying for exams though ultimately electing not to apply for colleges. While he’s away in the army, Huen’s letters to him become increasingly infrequent until Wen’s start coming back return to sender, the other soldiers mocking him for his devotion to his hometown girlfriend while suggesting that she has most likely moved on, a supposition which turns out to be correct in the extremely ironic nature of her new suitor.

Yet it’s not quite true that everything is rosy in the country and rotten in the city. On a visit home, Wen overhears his father and some of the other coal miners discussing a potential strike action feeling themselves exploited and under appreciated, while later that evening a group of boys who also left for Taipei lament their circumstances afraid to explain to their parents that things aren’t going well and that they’ve been physically abused by their employers. Ironically enough it’s Wen who can’t seem to gel with city life, becoming frustrated by Huen’s ability to go with the flow having a minor patriarchal tantrum when she accepts a drink from his male friends at a going away party for a man about to enlist. She responds by voluntarily removing her shirt for an artist friend to decorate, staring at him with scorn while waiting around in her vest. In the village everyone is disappointed, feeling as if Huen has betrayed Wen in failing to fulfil their romantic destiny though it is often enough he who has alienated her in his prideful stubbornness, continually cold towards her, leaving her lonely and afraid. Had they stayed, perhaps they would have married, had children, grown old and done all the expected things together and in that sense “modernity” has indeed come between them but then again they were children and what teenage lovers don’t assume they’re “supposed” to be? “What can you do?” come the words from stoical granddad (Li Tian-lu), explaining that his transplanted potatoes haven’t fared well in the recent storm.

While Wen’s father can only lament the toll changing political realities took on his future prospects, literally moving rocks around in drunken bouts of frustrated masculinity, Wen must struggle with his familial legacy while wondering if perhaps it’s better in the village after all ensconced in the beautiful rural landscape far from the consumerist corruptions of increasing urbanity. But then according to granddad, the potatoes only accept the nutrient when severed from the vine, much harder to look after than ginseng, apparently. You have to wander in order to find a home, life is hard everywhere, sometimes painful and disappointing, but what can you do? Like dust in the wind, try your best to ride it out.

Dust in the Wind streams in the UK 25th to 31st October as part of this year’s Taiwan Film Festival Edinburgh.

Trailer (Traditional Chinese / English subtitles)