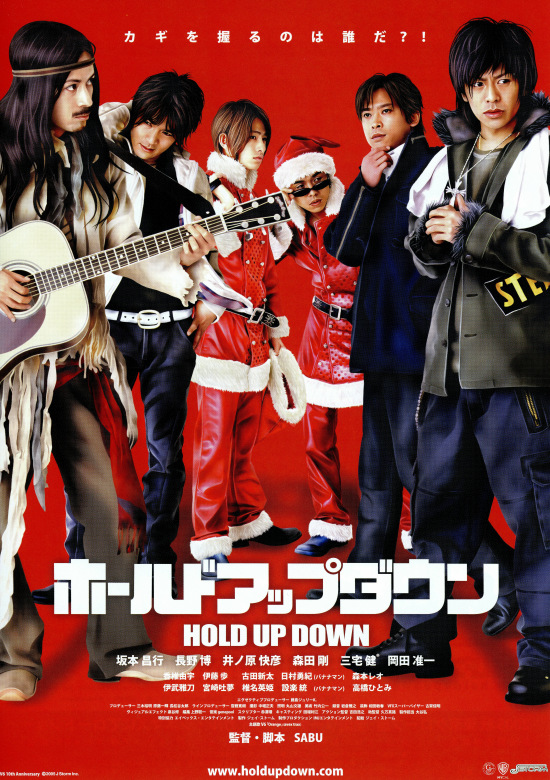

Reteaming with popular boy band V6, SABU returns with another madcap caper in the form of surreal farce Hold Up Down (ホールドアップダウン). Holding up is, as usual, not on SABU’s roadmap as he proceeds at a necessarily brisk pace, weaving these disparate plot strands into their inevitable climax. Perhaps a little shallower than the director’s other similarly themed offerings, Hold Up Down mixes everything from reverse Father Christmasing gone wrong, to gun obsessed policemen, train obsessed policewomen, clumsy defrocked priests carrying the cross of frozen Jesus, and a Shining-esque hotel filled with creepy ghosts. Quite a lot to be going on with but if SABU has proved anything it’s that he’s very adept at juggling.

Reteaming with popular boy band V6, SABU returns with another madcap caper in the form of surreal farce Hold Up Down (ホールドアップダウン). Holding up is, as usual, not on SABU’s roadmap as he proceeds at a necessarily brisk pace, weaving these disparate plot strands into their inevitable climax. Perhaps a little shallower than the director’s other similarly themed offerings, Hold Up Down mixes everything from reverse Father Christmasing gone wrong, to gun obsessed policemen, train obsessed policewomen, clumsy defrocked priests carrying the cross of frozen Jesus, and a Shining-esque hotel filled with creepy ghosts. Quite a lot to be going on with but if SABU has proved anything it’s that he’s very adept at juggling.

Christmas Eve – two guys hold up a bank whilst cunningly disguised as Santas, but emerging with the money they find their getaway car getting away from them on the back of a tow truck. Still dressed as Father Christmases, the guys head for the subway and decide to stash the cash in a coin locker only neither of them has any change. After robbing a busker at gunpoint for 800 yen, the duo get rid of the loot but the guy chases after them at which point they lose the key which the busker swallows after being hit by a speeding police car. Trying to cover up the crime the two policeman bundle him into the car but crash a short time later at which time the busker gets thrown in a lake and then retrieved by a defrocked priest under the misapprehension that he is Japanese Jesus!

Following SABU’s usual spiralling chase formula, events quickly escalate as one random incident eventually leads to another. Christmas is a time of romance in Japan, though encountering the love of your life during a bank robbery is less than ideal. After a love at first sight moment heralded by a musical cue, the thieves head back on the run with the girl in tow but the course of true love never did run smooth. If romance is one motivator – death is another. On this holiest of days, our defrocked priest is caught in a moment of despair, contemplating the ultimate religious taboo in taking his own life and ending the torment he feels in having failed God so badly. Therefore, when our scruffy hippy busker washes up right nearby he draws the obvious conclusion – Jesus has returned to save him! Attempting to make up for his numerous mistakes, the priest is determined to save and preserve his Lord, but, again, his clumsiness results in more catastrophes.

The situation resolves itself as each of the players winds up at the same abandoned hot springs resort which turns out to be not quite so closed down as everyone thought. Filled with ghostly charm, the gloomy haunted house atmosphere sends everyone over the edge as they thrash out their various issues as if possessed by madness. Culminating in a sequence of extreme slapstick in which everyone fights with everyone else and frozen Jesus plays an unexpectedly active part, Hold Up Down brings all of its surreal goings on to a suitably absurd conclusion in which it seems perfectly reasonable that those wishing to leave limbo land could take a 2.5hr bus trip back to the afterlife.

Pure farce and lacking the heavier themes of other SABU outings, Hold Up Down, can’t help but feel something of a lightweight exercise but that’s not to belittle the extreme intricacy of the plotting or elegance of its resolution. An innovativeIy integrated early fantasy sequence begins the voyage into the surreal which is completed in the strangely spiritual haunted house set piece as the disillusioned priest spends some time with congenial demons before attempting to make his peace with God only for it all to go wrong again. If there is a god here, it’s the Lord of Misrule but thankfully they prove a benevolent one as somehow everything seems to shake itself out with each of our troubled protagonists discovering some kind of inner calm as a result of their strange adventure, as improbable as it seems (in one way or another). Christmas is a time for ghost stories, after all, but you’ll rarely find one as joyful as Hold Up Down.

Scene from the end of the film:

Tradition vs modernity is not so much of theme in Japanese cinema as an ever present trope. The characters at the centre of Yukiko Mishima’s adaptation of Aoi Ikebe’s manga, A Stitch of Life (繕い裁つ人, Tsukuroi Tatsu Hito), might as well be frozen in amber, so determined are they to continuing living in the same old way despite whatever personal need for change they may be feeling. The arrival of an unexpected visitor from what might as well be the future begins to loosen some of the perfectly executed stitches which have kept the heroine’s heart constrained all this time but this is less a romance than a gentle blossoming as love of craftsmanship comes to the fore and an artist begins to realise that moving forward does not necessarily entail a betrayal of the past.

Tradition vs modernity is not so much of theme in Japanese cinema as an ever present trope. The characters at the centre of Yukiko Mishima’s adaptation of Aoi Ikebe’s manga, A Stitch of Life (繕い裁つ人, Tsukuroi Tatsu Hito), might as well be frozen in amber, so determined are they to continuing living in the same old way despite whatever personal need for change they may be feeling. The arrival of an unexpected visitor from what might as well be the future begins to loosen some of the perfectly executed stitches which have kept the heroine’s heart constrained all this time but this is less a romance than a gentle blossoming as love of craftsmanship comes to the fore and an artist begins to realise that moving forward does not necessarily entail a betrayal of the past.

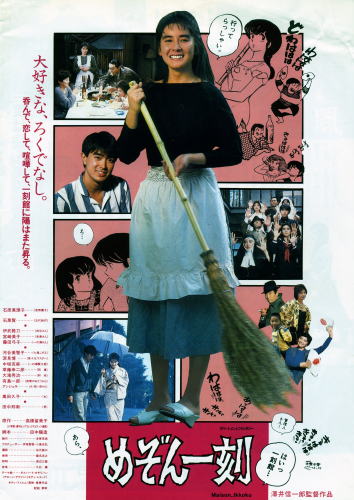

Sometimes love makes you do crazy things. Some people find themselves accomplishing previously unattainable feats powered only by the sheer force of romance. Unfortunately for the hero of Swimming Upstream (バタアシ金魚, Bataashi Kingyo), Joji’s Matsuoka’s adaptation of Minetaro Mochizuki’s manga, the task he sets for himself is a very lofty one indeed and may actually require him to abandon his love to complete it. Then again, the object of his affections shows little signs of reciprocation in any case.

Sometimes love makes you do crazy things. Some people find themselves accomplishing previously unattainable feats powered only by the sheer force of romance. Unfortunately for the hero of Swimming Upstream (バタアシ金魚, Bataashi Kingyo), Joji’s Matsuoka’s adaptation of Minetaro Mochizuki’s manga, the task he sets for himself is a very lofty one indeed and may actually require him to abandon his love to complete it. Then again, the object of his affections shows little signs of reciprocation in any case. If you’ve always fancied a stay at that inn the

If you’ve always fancied a stay at that inn the  A late career entry from socially minded director Shohei Imamura, Dr. Akagi (カンゾー先生, Kanzo Sensei) takes him back to the war years but perhaps to a slightly more bourgeois milieu than his previous work had hitherto focussed on. Based on the book by Ango Sakaguchi, Dr. Akagi is the story of one ordinary “family doctor” in the dying days of World War II.

A late career entry from socially minded director Shohei Imamura, Dr. Akagi (カンゾー先生, Kanzo Sensei) takes him back to the war years but perhaps to a slightly more bourgeois milieu than his previous work had hitherto focussed on. Based on the book by Ango Sakaguchi, Dr. Akagi is the story of one ordinary “family doctor” in the dying days of World War II. 2009 marked the centenary year of Osamu Dazai, a hugely important figure in the history of Japanese literature who is known for his melancholic stories of depressed, suicidal and drunken young men in contemporary post-war Japan. Villon’s Wife (ヴィヨンの妻 〜桜桃とタンポポ, Villon no Tsuma: Oto to Tampopo) is a semi-autobiographical look at a wife’s devotion to her husband who causes her nothing but suffering thanks to his intense insecurity and seeming desire for death coupled with an inability to successfully commit suicide.

2009 marked the centenary year of Osamu Dazai, a hugely important figure in the history of Japanese literature who is known for his melancholic stories of depressed, suicidal and drunken young men in contemporary post-war Japan. Villon’s Wife (ヴィヨンの妻 〜桜桃とタンポポ, Villon no Tsuma: Oto to Tampopo) is a semi-autobiographical look at a wife’s devotion to her husband who causes her nothing but suffering thanks to his intense insecurity and seeming desire for death coupled with an inability to successfully commit suicide.