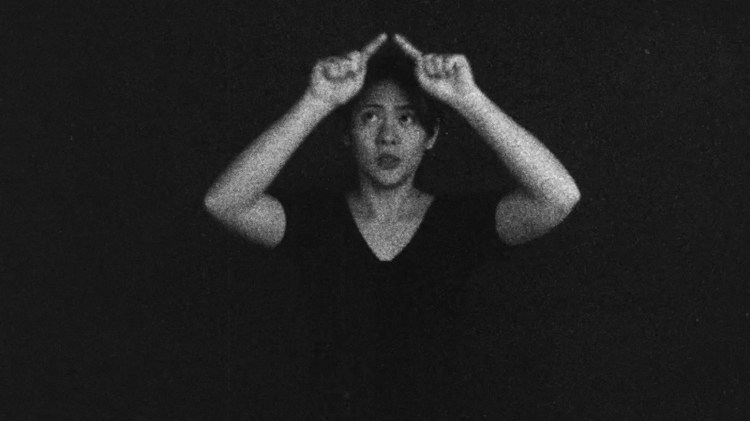

“The convict loves her executioner, the thief loves her jailer. We love you. We have no other choice.” the hero of Zhang Yuan’s beguiling, transgressive drama East Palace, West Palace (东宫西宫, dōng gōng xī gōng), whispers to his no longer sleeping guard. “I love you”, he later adds, “why don’t you love me?” turning the tables on an implacable authority and demonstrating that he too wields power. Considered the first Mainland film to deal directly with homosexuality, Zhang’s theatrical chamber piece is as much about the co-dependency of the oppressor and the oppressed as it is about gay life in post-Tiananmen Beijing while suggesting that in a sense submission too can be a weapon.

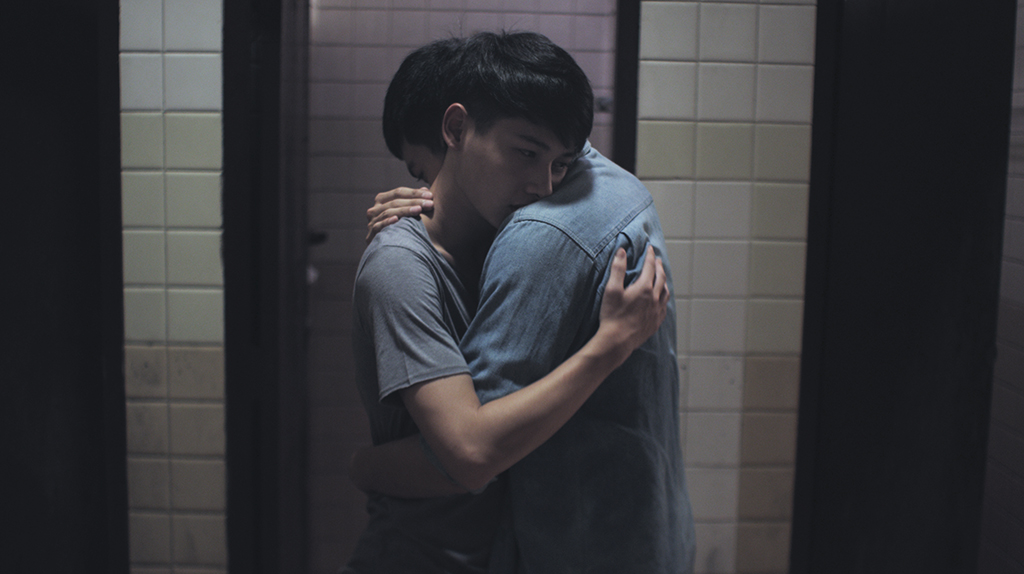

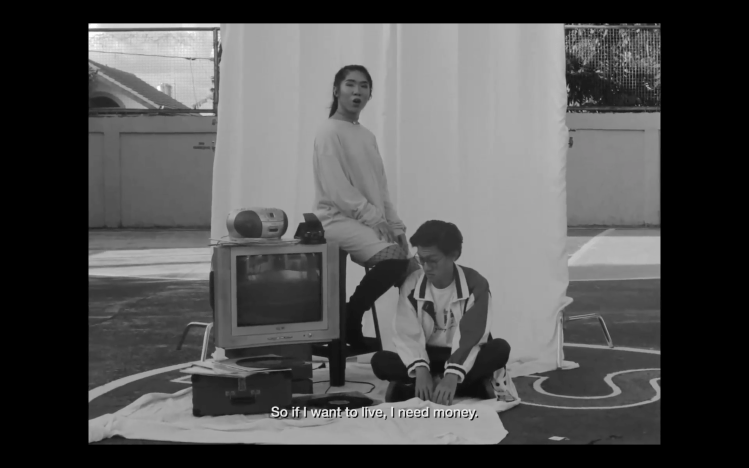

Gay travel writer A-Lan (Si Han) is first challenged by a uniformed policeman in a public toilet. Staring at him intently, he stops A-Lan for no real reason, asking for his ID followed by a series of other personal questions with seemingly no law enforcement import before double checking if the bike outside is his and that he has a proper permit for it. These acts of hostility begin a cat and mouse game between the A-Lan and law enforcement, another policeman, Shi Xiaohua (Hu Jun), almost desperate to come up with a reason to arrest him on raiding the park, a popular spot for cruising, after dark. But as he leads him away, A-Lan suddenly plants a kiss on the policeman’s cheek and taking advantage of his momentary shock makes his escape.

During in the arrest, meanwhile, Shi and the other policemen had a made a point of insulting each of the men who have not actually done anything illegal under the Chinese law of the time, beating them or forcing them to beat themselves, ordering them to squat on the ground, and even threatening to call one frequent offender’s place of work. As Shi often will, the police refer to the men as “despicable” and the “dregs of soceity”, yet A-Lan is in a sense empowered by his submission in allowing himself to be arrested before subsequently escaping having planted the seeds of his seduction. He flirts with danger in mailing Shi a book with the inscription “To my love, A-Lan” and thereafter deliberately gets himself arrested, later running away from Shi only in the desire to be chased by him.

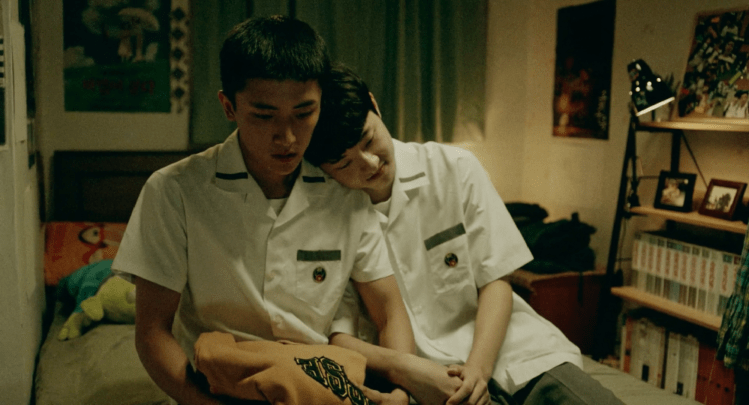

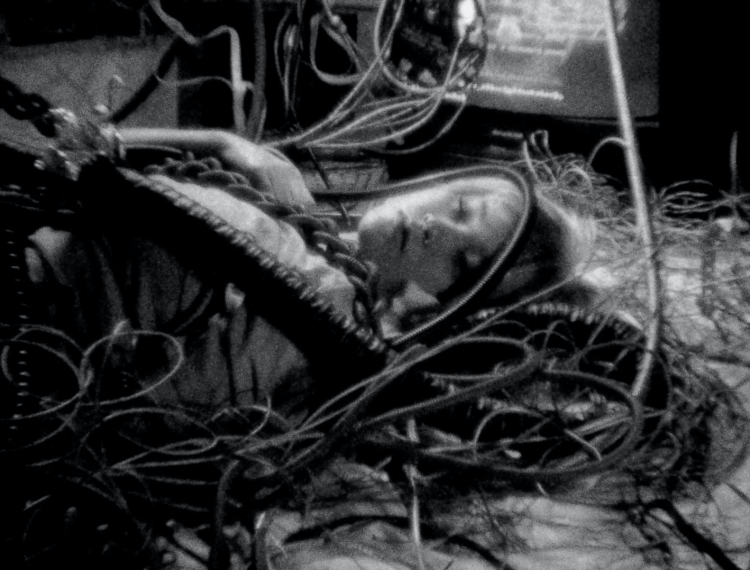

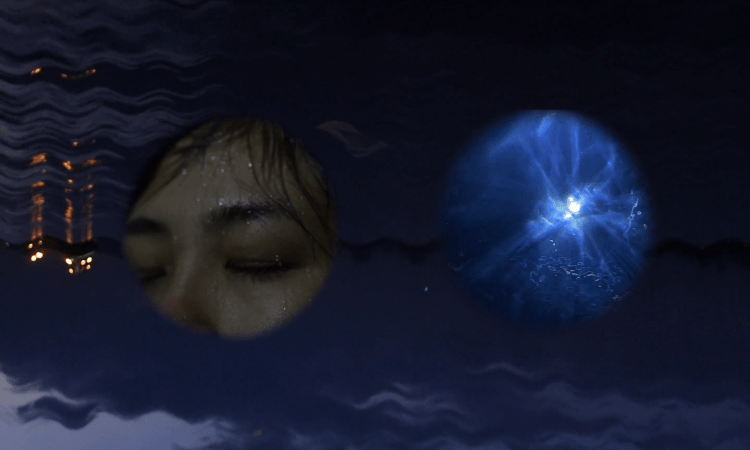

Hugely reminiscent of Kiss of the Spider Woman, the majority of the film takes place within the confines of the park’s police hut occupied only by A-Lan and Shi, a prisoner and a guard. Yet as in the Peking opera story A-Lan repeatedly quotes, elegantly recreated in Zhang’s theatrical shifts into fantasy, the two roles are to an extent interchangeable. Shi thinks he’s the guard, that he exercises authority over A-Lan, but A-Lan is also manipulating him, trapping Shi within this space and drawing him towards a recognition of his own latent desires, the same desires that were aroused when he hassled him in the public toilet. While Shi, the guard though no longer in uniform, is constrained by authority, A-Lan, the prisoner, is free in embracing his essential self and weaponising the essence of his power in the choice to submit as reflected in his masochistic desires. “It is not despicable. It is love” he insists on being challenged by Shi after detailing his BDSM encounter with a wealthy man, echoing his previous reminders that “What I write might be trash. But I am not”, refusing to allow Shi to degrade him even while taking pleasure in submitting to authority.

Even so, he declares himself conflicted in having married a woman presumably for appearances’ sake something of which many in his community do not approve and leaves him both guilty in his treatment of his wife and disappointed in himself. When Shi barks “explain yourself” he details his life as a gay man from his first sexual experience in which he pretended to be a woman to being assaulted by thugs after sleeping with a factory boss adding only that “this kind of experience makes life with living”. “We all march to a different tune” he tries to explain to Shi, individual but also identical. He mentions another regular to the park he describes as a transvestite but in the language of today might better be thought of as transgender, A-Lan explaining that she enjoys wearing women’s clothes but is different from the men in the park. She does not make love to them, and they do not bother with her, A-Lan insisting that she too has her own beat to which to march as does Shi even in his increasing confusion.

Shi wields his handcuffs, the relationship between the pair mediated through them just as that between the guard and beautiful prisoner in his story is mediated through chains, but eventually places the cuffs on each of their hands locking them together in an intense embrace. The guard cannot exist without the prisoner, nor the prisoner without the guard. “He will no longer escape from his love for her” A-Lan ends his story, the guard releasing his beautiful charge while she decides to return to him each of them knowing they are trapped in melancholy waltz of love and hate. Highly theatrical and scored with a persistent note of dread, Zhang’s beguiling drama hints at the sadomasochistic interplay between authoritarian power and a subjugated populace while allowing its hero to mount his resistance only through deriving pleasure from submission.

East Palace, West Palace screens at the BFI on 27th May as part of this year’s Queer East. It is also available to stream in many territories via GagaOOLala.