The way of the sword is fraught with contradictions. Like many martial arts, kendo is not primarily intended for practical usage but for self improvement, emotional centring, and fostering a big hearted love of country designed to ensure lasting peace between men. Nevertheless, it tends to attract people who struggle with just those issues, hoping to find the peace within themselves though mastery of the sword. Kazuyoshi Kumakiri’s long and varied career has often focussed on outsiders dealing with extreme emotions and Mukoku (武曲 MUKOKU) is no different in this regard as the two men at its centre lock swords at cross purposes, each fighting something or someone else within themselves rather than the flesh and blood opponent standing before them.

The way of the sword is fraught with contradictions. Like many martial arts, kendo is not primarily intended for practical usage but for self improvement, emotional centring, and fostering a big hearted love of country designed to ensure lasting peace between men. Nevertheless, it tends to attract people who struggle with just those issues, hoping to find the peace within themselves though mastery of the sword. Kazuyoshi Kumakiri’s long and varied career has often focussed on outsiders dealing with extreme emotions and Mukoku (武曲 MUKOKU) is no different in this regard as the two men at its centre lock swords at cross purposes, each fighting something or someone else within themselves rather than the flesh and blood opponent standing before them.

Kengo Yatabe’s (Go Ayano) life has been defined by the sword. As a young boy his father, Shozo (Kaoru Kobayashi), began training Kengo intensively but his standards were high, too high for a small boy who only wanted to please his dad but found himself beaten with the weapon he was failing to master. Twenty years later Kengo is a broken man after a long deferred violent confrontation between father and son has left Shozo in a vegetative state, neither dead nor alive, no longer a figure of fear and hate but of guilt and ambivalence. Kengo has given up kendo partly out of guilt but also as a kind of rebellion mixed with self harm and is currently working as a security guard. He spends his days lost in an alcoholic fog, trailing an equally drunken casual girlfriend (Atsuko Maeda) behind him.

Meanwhile, high school boy Toru (Nijiro Murakami) is a classic angry young man working out his frustrations through a hip-hop infused punk band for which he writes the angst ridden poetry that serves as their lyrics. Toru has no interest in something as stuffy as Kendo but when he’s set upon by a bunch of Kendo jocks he decides he’s not going down without a fight. Winning through underhanded street punk moves would normally be frowned upon but the ageing monk who runs the high school kendo club, Mitsumura (Akira Emoto), is struck by his nifty footwork and decides to convince the troubled young man that the path to spiritual enlightenment lies in mastery over the self through mastery of the sword.

The wise old monk pits the self-destructive older man against the scrappy young one, hoping to bring them both to some kind of peaceful equilibrium, with near tragic results. Kengo’s ongoing troubles are born of a terrible sense of guilt, but also from intense self-loathing in refusing to accept that he’s become the man he hated, as broken and embittered as the father who made him that way. Shozo was a kendo master, but as the monk points out, in technique only – his heart was forever unquiet and he never achieved the the true peace necessary to master his art. Knowing this to be the truth only made it worse yet Shozo also knew the burden he’d placed on his son. They say every man must kill his father, but Kengo can’t let the ghost of his go – clinging on to a mix of filial piety and resentful loathing which is slowly turning him into everything he hates.

Toru’s problem’s are pushed into the background but seeing as his enemy is not the flesh and blood threat of an overbearing father but the elements and more particularly water, it will be much harder to overcome. Water becomes a constant symbol for each man – for Toru it’s an inescapable symbol of death and powerlessness, but for Kengo it represents happiness and harmony in rediscovering the good memories he has of his father from joyful family outings to less abusive summer training sessions. Mukoku is the story of three ages of man – the scrappy rebellious teen, the struggling middle-aged man, and the elderly veteran whose own heart is settled enough to see the battles others are waging. The “warrior’s song” as “mukoku” seems to mean changes with each passing season, nudged into tune by the graceful art of kendo.

Kumakiri embraces his expressionist impulses as a young boy finds himself suddenly underwater, vomiting mud and fish while Kengo has constant visions of his father, mother, and younger self ensuring the past is forever present. The ominous score and strange occurrences including ghostly graveyard old women who appear from nowhere in order to offer a lecture on the five buddhist sins lend a more urgent quality to Kengo’s disintegration, though interesting subplots involving a possibly alcoholic girlfriend and a mamasan (Jun Fubuki) at a local bar who might have been Shozo’s mistress are left underdeveloped. Two men face each other to face themselves, trying to beat their demons into submission with wooden swords, but even if the battle is far from over the tide has turned and something at least has begun to shift.

Screened at Raindance 2017.

Original trailer (no subtitles)

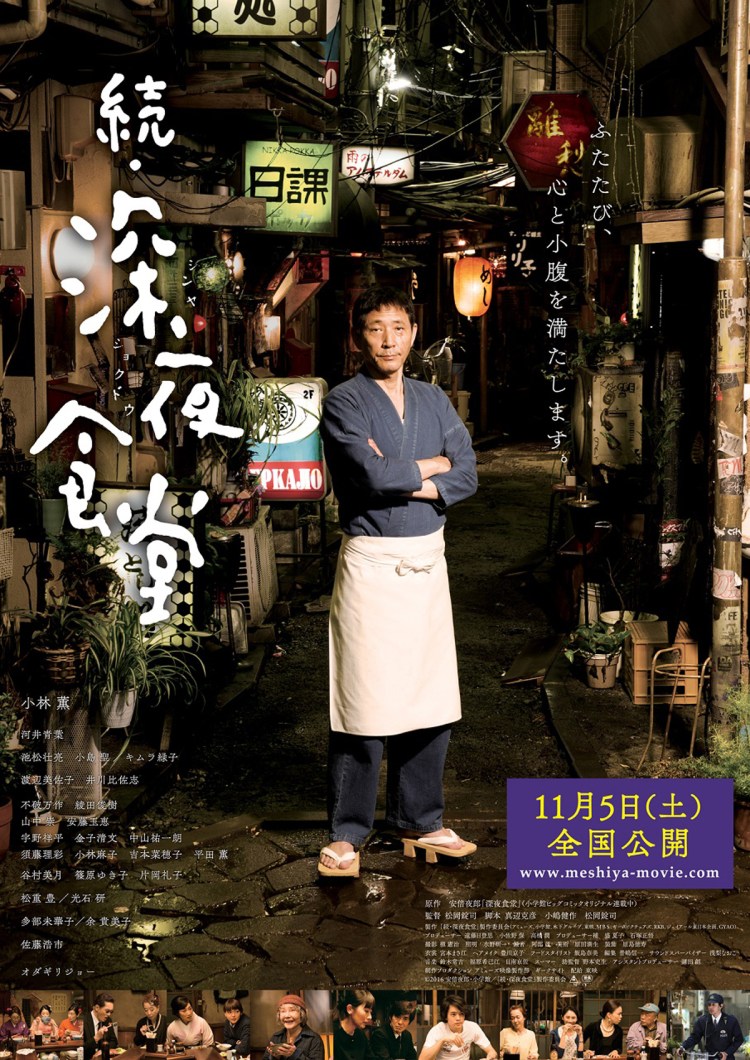

The Midnight Diner is open for business once again. Yaro Abe’s eponymous manga was first adapted as a TV drama in 2009 which then ran for three seasons before heading to the

The Midnight Diner is open for business once again. Yaro Abe’s eponymous manga was first adapted as a TV drama in 2009 which then ran for three seasons before heading to the

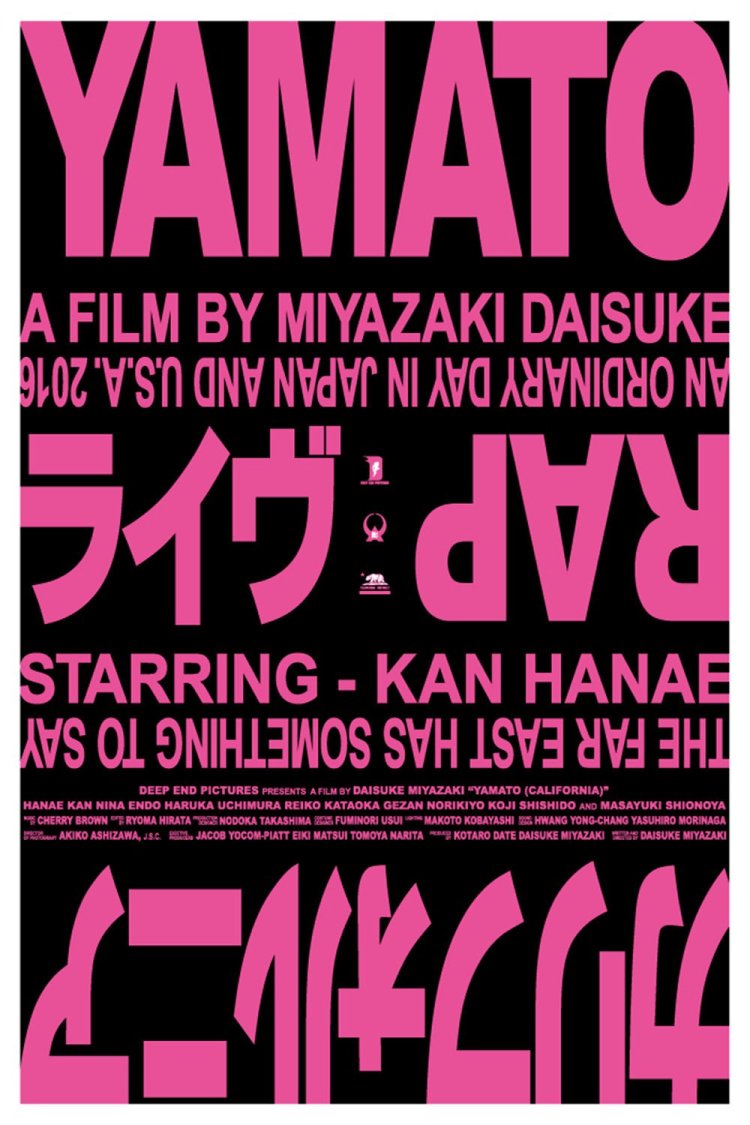

When you think of the American military presence in Japan, your mind naturally turns to Okinawa but the largest mainland US base is actually located not so far from Tokyo in a small Japanese town called Yamato which is also the ancient name for the modern-day country. The US has been a constant presence since the end of the second world war prompting resistance of varying degrees from both left and right either in resentment at perceived complicity in American foreign policy, or the desire to reform the pacifist constitution and rebuild an independent army capable of defending Japan alone. Daisuke Miyazaki’s second feature, Yamato (California) (大和(カリフォルニア) dramatises this long-standing issue through exploring the life of hip-hop enthusiast and Yamato resident Sakura (Hanae Kan) who idolises an art form born of political oppression in a country which she also feels oppresses her as a Japanese citizen living on the other side of the fence from land which technically still belongs to the US government.

When you think of the American military presence in Japan, your mind naturally turns to Okinawa but the largest mainland US base is actually located not so far from Tokyo in a small Japanese town called Yamato which is also the ancient name for the modern-day country. The US has been a constant presence since the end of the second world war prompting resistance of varying degrees from both left and right either in resentment at perceived complicity in American foreign policy, or the desire to reform the pacifist constitution and rebuild an independent army capable of defending Japan alone. Daisuke Miyazaki’s second feature, Yamato (California) (大和(カリフォルニア) dramatises this long-standing issue through exploring the life of hip-hop enthusiast and Yamato resident Sakura (Hanae Kan) who idolises an art form born of political oppression in a country which she also feels oppresses her as a Japanese citizen living on the other side of the fence from land which technically still belongs to the US government. Ryosuke Hashiguchi returns after an eight year absence with All Around Us (ぐるりのこと。Gururi no Koto) and eschews most of his pressing themes up this by point by opting to depict a few “scenes from a marriage” in post-bubble era Japan. Set against the backdrop of an extremely turbulent decade which was plagued by natural disasters, terrorism, and shocking criminal activity Hashiguchi shows us the enduring love of one ordinary couple who, finding themselves pulled apart by tragedy, gradually grow closer through their shared grief and disappointment.

Ryosuke Hashiguchi returns after an eight year absence with All Around Us (ぐるりのこと。Gururi no Koto) and eschews most of his pressing themes up this by point by opting to depict a few “scenes from a marriage” in post-bubble era Japan. Set against the backdrop of an extremely turbulent decade which was plagued by natural disasters, terrorism, and shocking criminal activity Hashiguchi shows us the enduring love of one ordinary couple who, finding themselves pulled apart by tragedy, gradually grow closer through their shared grief and disappointment. The family drama is a mainstay of Japanese cinema, true, but, it’s a far wider genre than might be assumed. The rays fracture out from Ozu through to

The family drama is a mainstay of Japanese cinema, true, but, it’s a far wider genre than might be assumed. The rays fracture out from Ozu through to  Ryosuke Hashiguchi’s debut feature A Touch of Fever (二十才の微熱, Hatachi no Binetsu) proved a surprise box office hit in Japan and is also credited for helping to bring male homosexuality into the mainstream. A no-budget movie shot on 16mm, A Touch of Fever is the story of two ordinary boys each going about their everyday lives whilst also beginning to understand themselves in terms of their sexualities, mirroring each other perfectly in their inner confusion.

Ryosuke Hashiguchi’s debut feature A Touch of Fever (二十才の微熱, Hatachi no Binetsu) proved a surprise box office hit in Japan and is also credited for helping to bring male homosexuality into the mainstream. A no-budget movie shot on 16mm, A Touch of Fever is the story of two ordinary boys each going about their everyday lives whilst also beginning to understand themselves in terms of their sexualities, mirroring each other perfectly in their inner confusion.