“Have you ever seen an old movie and not been able to get it out of your head?” For those of us who grew up in the pre-internet age, daytime television was a treasure trove of classic cinema where unexpected discoveries were made. Maybe you only caught a few minutes of a film whose title you never knew, but the images are burned into your brain like nothing before or since. It’s tempting, then, to wonder if it isn’t Muroi (Yurei Yanagi), the nascent director, who’s projecting the darkest corners of his mind onto this haunted celluloid, though as it turns out this film was never actually aired.

If Muroi saw the haunted film as a child, it was because the ghost within it chose to broadcast herself by hijacking the airwaves. As his friend points out, however, perhaps he just saw a newspaper report about an actress dying in an on-set fall and saw it in his mind, creating a movie of his own or perhaps a waking nightmare that continues to plague him into adulthood. In any case, the film he’s trying to make is a wartime melodrama rather than a ghost story, but it’s one that’s clearly built around dark secrets and hidden desires. Hitomi (Yasuyo Shirashima) reveals that her character killed her mother in the film to take her place and later kills a deserting soldier with whom she’s been in some kind of relationship that the younger sister threatens to reveal in fear that should the villagers find out they’ve been hindering the war effort by hiding a man who’s shirked his duty to the nation they’ll be ostracised and people will stop sharing their food with them.

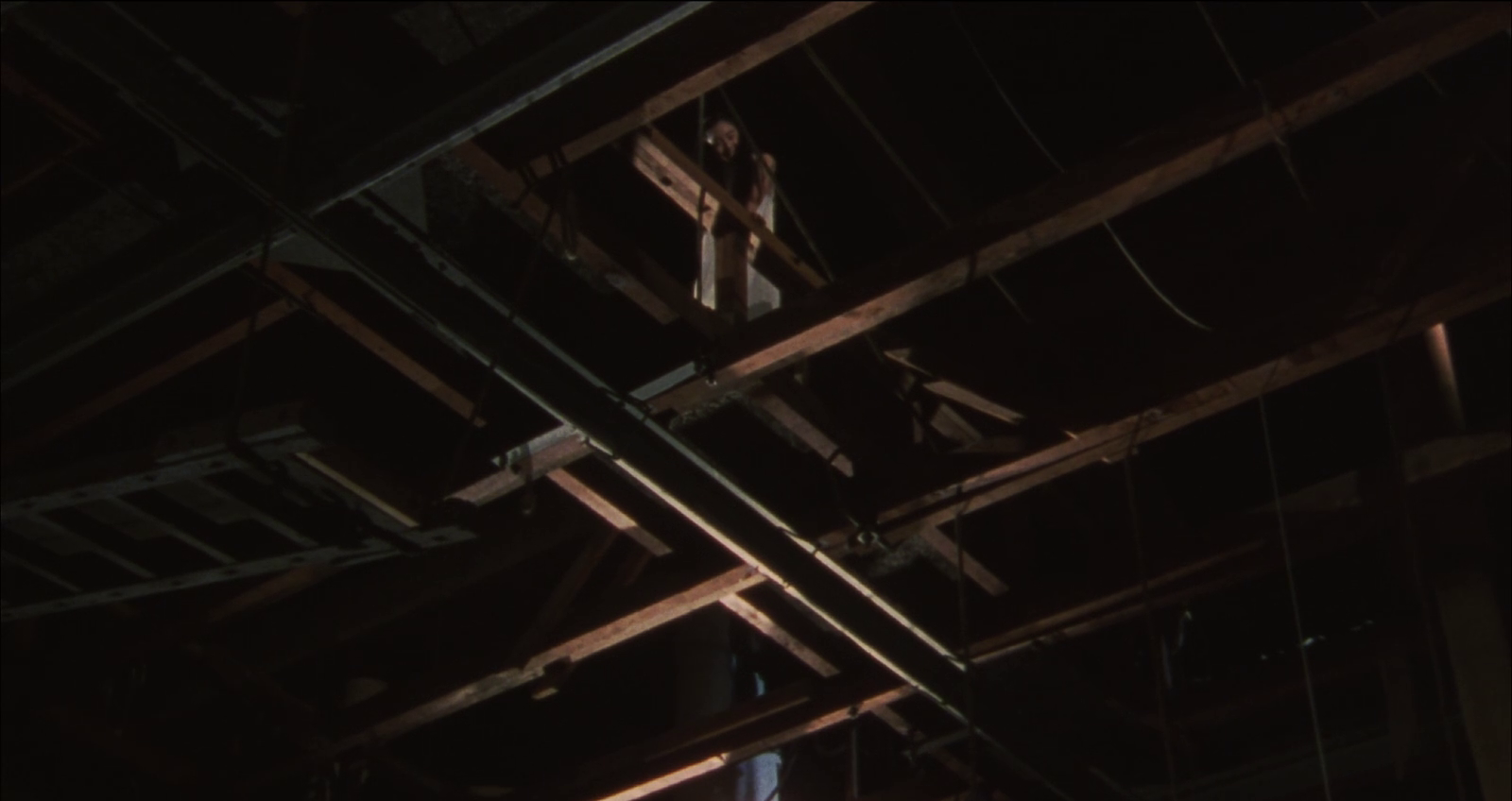

But Hitomi has real-world issues too. There’s something going on with her overbearing manager who seemingly didn’t want her to do this film which is why she’s not on set with her. When she eventually turns up, she seems to have some psychic powers. After handing Hitomi an amulet, she runs from the studio screaming. Hitomi agrees there’s something eerie about this place. As the projectionist remarks, this studio is 50 years old, built during the post-war relaunch of the cinema industry. Many things have happened here. But Nikkatsu is now a ghost itself and these disused production facilities are a haunted spaced. The floorboards creak and the rigging may give way any moment, bringing down with it the dream of cinema.

That’s one reason Muroi is advised not to look up and break this sense of allusion, along with recalling the more recent tragedy of an actress’ accidental fall. As much as Hitomi and Saori (Kei Ishibashi) begin to overlap with the image of the ghostly actress, it’s Muroi who is eventually swallowed by his dream of cinema in his determination to climb the stairs and find out what horrors are lurking in the attic before being dragged away to some other world. Nevertheless, this is a film that could only be made with celluloid. Nakata slips back and fore between the film that we’re watching and the cursed negative with its ghost images from previous exposure. This is evidently a low-budget production too, made using end cuts from other reels. As someone points out, this unused footage would usually be thrown out but has somehow mysteriously ended up infecting their film and releasing its ghosts. The projectionist burns it, describing the film as “evil” and suggesting that it’s better to let sleeping dogs lie.

But Muroi seems unable to let it go, chasing his childhood nightmare in trying to explain the mystery behind the footage. Hitomi describes herself as being haunted by a role long after the film as ended. It’s the same when someone dies, she says. They hang on for a while. The actor too remarks that he feels like the camera hates him, as if he were feeling the ghost’s wrath directly but otherwise unable to see her. Yet we have this sense of history repeating and a curse that’s sure to recur while this film too will remain unfinished and linger in the realm of the unrealised. Nakata too only undertook this film after losing his job to Nikkatsu’s collapse and trying to finance a documentary about Joseph Losey as if captivated by his own dream of the cinematic past and the haunting images of a bygone world.

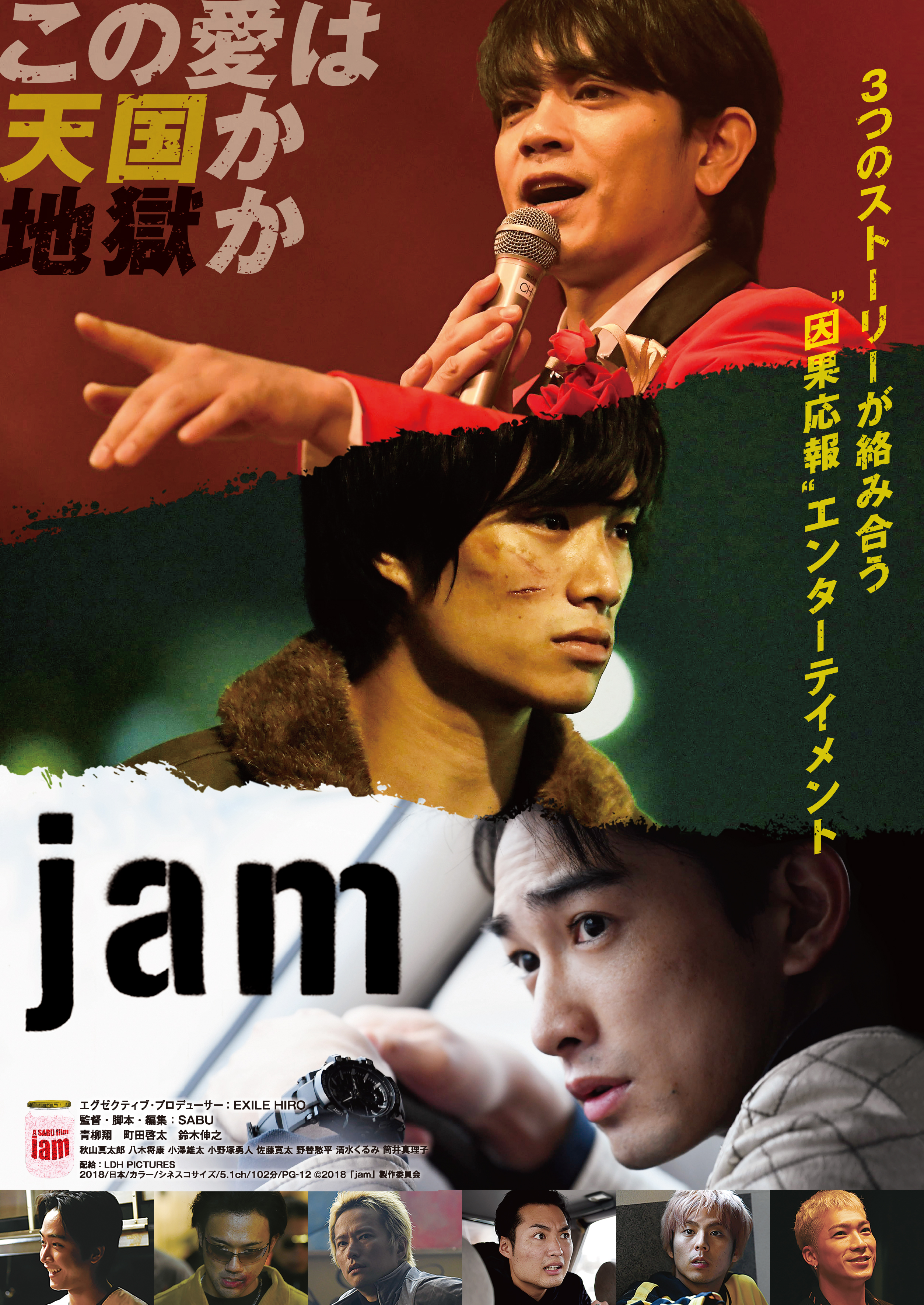

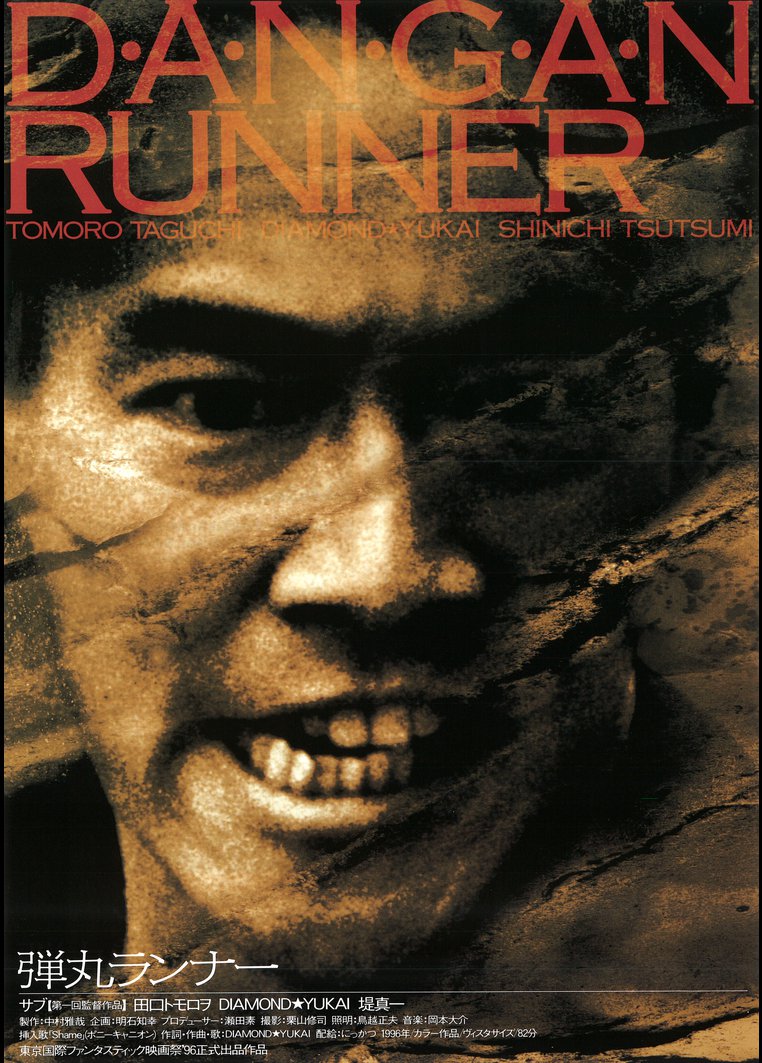

Taiwan and Japan have a complicated history, but in SABU’s latest slice of cross-cultural interplay each place becomes a kind of refuge from the other. Working largely in Mandarin and with Taiwanese star Chang Chen, SABU returns to a familiar story – the lonely hitman tempted by a normal family life filled with peace and simplicity only to have his dreams taken from him by the spectre of his past. Only this time it isn’t just his past but that of others too. Despite the melancholy air, Mr. Long (ミスター・ロン) is a testament to the power of simple human kindness but also a condemnation of underworld cruelty and its vicelike grip on all who enter its grasp.

Taiwan and Japan have a complicated history, but in SABU’s latest slice of cross-cultural interplay each place becomes a kind of refuge from the other. Working largely in Mandarin and with Taiwanese star Chang Chen, SABU returns to a familiar story – the lonely hitman tempted by a normal family life filled with peace and simplicity only to have his dreams taken from him by the spectre of his past. Only this time it isn’t just his past but that of others too. Despite the melancholy air, Mr. Long (ミスター・ロン) is a testament to the power of simple human kindness but also a condemnation of underworld cruelty and its vicelike grip on all who enter its grasp. “Memories are what warm you up from the inside. But they’re also what tear you apart” runs the often quoted aphorism from Haruki Murakami. SABU seems to see things the same way and indulges an equally surreal side of himself in the sci-fi tinged Happiness (ハピネス). Memory, as the film would have it, both sustains and ruins – there are terrible things which cannot be forgotten, no matter how hard one tries, while the happiest moments of one’s life get lost among the myriad everyday occurrences. Happiness is the one thing everyone craves even if they don’t quite know what it is, little knowing that they had it once if only for a few seconds, but if the desire to attain “happiness” is itself a reason for living could simply obtaining it by technological means do more harm than good?

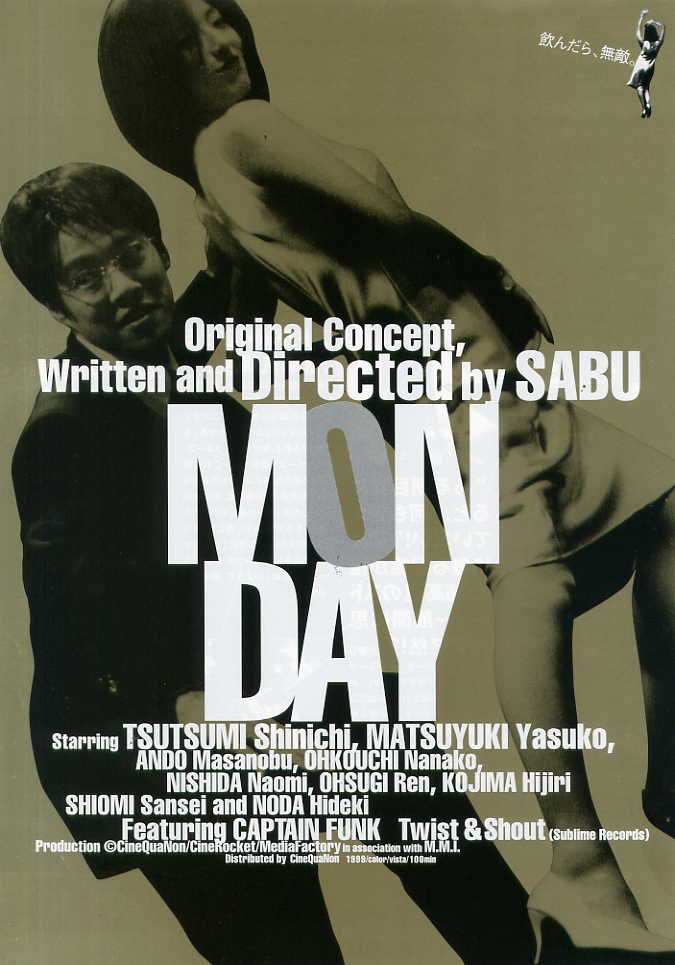

“Memories are what warm you up from the inside. But they’re also what tear you apart” runs the often quoted aphorism from Haruki Murakami. SABU seems to see things the same way and indulges an equally surreal side of himself in the sci-fi tinged Happiness (ハピネス). Memory, as the film would have it, both sustains and ruins – there are terrible things which cannot be forgotten, no matter how hard one tries, while the happiest moments of one’s life get lost among the myriad everyday occurrences. Happiness is the one thing everyone craves even if they don’t quite know what it is, little knowing that they had it once if only for a few seconds, but if the desire to attain “happiness” is itself a reason for living could simply obtaining it by technological means do more harm than good? Waking up in an unfamiliar hotel room can be a traumatic and confusing experience. The hero of SABU’s madcap amnesia sit in odyssey finds himself in just this position though he is, at least, fully clothed even if trying to think through the fog of a particularly opaque booze cloud. Monday (マンデイ) is film about Saturday night, not just literally but mentally – about a man meeting his internal Saturday night in which he suddenly lets loose with all that built up tension in an unexpected, and very unwelcome, way.

Waking up in an unfamiliar hotel room can be a traumatic and confusing experience. The hero of SABU’s madcap amnesia sit in odyssey finds himself in just this position though he is, at least, fully clothed even if trying to think through the fog of a particularly opaque booze cloud. Monday (マンデイ) is film about Saturday night, not just literally but mentally – about a man meeting his internal Saturday night in which he suddenly lets loose with all that built up tension in an unexpected, and very unwelcome, way. Reteaming with popular boy band V6, SABU returns with another madcap caper in the form of surreal farce Hold Up Down (ホールドアップダウン). Holding up is, as usual, not on SABU’s roadmap as he proceeds at a necessarily brisk pace, weaving these disparate plot strands into their inevitable climax. Perhaps a little shallower than the director’s other similarly themed offerings, Hold Up Down mixes everything from reverse Father Christmasing gone wrong, to gun obsessed policemen, train obsessed policewomen, clumsy defrocked priests carrying the cross of frozen Jesus, and a Shining-esque hotel filled with creepy ghosts. Quite a lot to be going on with but if SABU has proved anything it’s that he’s very adept at juggling.

Reteaming with popular boy band V6, SABU returns with another madcap caper in the form of surreal farce Hold Up Down (ホールドアップダウン). Holding up is, as usual, not on SABU’s roadmap as he proceeds at a necessarily brisk pace, weaving these disparate plot strands into their inevitable climax. Perhaps a little shallower than the director’s other similarly themed offerings, Hold Up Down mixes everything from reverse Father Christmasing gone wrong, to gun obsessed policemen, train obsessed policewomen, clumsy defrocked priests carrying the cross of frozen Jesus, and a Shining-esque hotel filled with creepy ghosts. Quite a lot to be going on with but if SABU has proved anything it’s that he’s very adept at juggling.

These days Takashi Miike is known as something of an enfant terrible whose rate of production is almost impossible to keep up with and regularly defies classification. Pressed to offer some kind of explanation to the uninitiated, most will point to the unsettling horror of

These days Takashi Miike is known as something of an enfant terrible whose rate of production is almost impossible to keep up with and regularly defies classification. Pressed to offer some kind of explanation to the uninitiated, most will point to the unsettling horror of