“Poor things, born in the wrong time,” a woman laments of two girls perhaps not that much younger than herself yet as trapped by the age of militarism as anyone else. Adapted from a short story by Edogawa Rampo, Shunya Ito’s gothic mystery Labyrinth Romanesque (花園の迷宮, Hanazono no Meikyu) effectively skewers militarism’s hypocrisies and lays bare the dehumanising effects its nihilistic philosophy has wrought on the nation as a whole. When killing is almost an imperative, life has little value and brutality seemingly the only acceptable response to mass violence.

Ito conjures a sense of haunting by adding a modern day framing sequence in which the abandoned hotel is an eerie space of cobweb-ridden collapse. A wrecking ball arcs back and fore, threatening to unearth a truth long buried and this is after all a mystery, at least in part. With extraordinary finesse, the camera travels from the ruins into the hotel of old as a woman enters the frame. We are now in 1942. This is Yokohama, a harbour town, and so the “hotel” is filled with military personnel though transgressively it also seems trapped in a kind of before time. The sailors dance to American standards such as Georgia on my Mind and Goodnight Sweetheart though otherwise at war with America. All eyes are on sex worker Yuri (Hitomi Kuroki) and her dashing Zero Fighter pilot boyfriend, Takemiya (Tatsuo Nadaka).

But later we learn that Takemiya hated planes and was scared of heights to the point that it kept him up at night. Apparently from a military family, he felt unable to avoid going on with this militaristic charade and saw no future for himself other than glorious death. Everyone at the Fukuju Hotel is in their way already dead and chief among them the madam, Tae (Yoko Shimada), who becomes the prime suspect when her unpleasant husband Ichitaro (Akira Nakao) is murdered during the night. Her nemesis is however. Ichitaro’s sister, Kiku (Kyoko Enami), who has just been deported from the US where she had been living after selling herself into sexual slavery in order to financially support Ichitaro after their parents died.

Kiku had been Tae’s madam, bringing her over from Japan at 17 and as she will do again, actively sitting on her face when she screamed and fought after being assigned her first customer. This brutalisation seems have driven Tae towards a desire for escape, but that was only available to her by marrying Ichiro who then betrayed his own sister to open another brothel that he ran with Tae before leaving the US and setting up in Yokohama in light of the declining relationship between America and Japan. Though she herself was brutalised, Tae can only earn her freedom by exploiting other women. At the beginning of the film two young girls, Mitsu (Mami Nomura), 18, and Fumi (Yuki Kudo), 17, arrive from the country excited for their new lives but without fully understanding what they’ve signed up to. Like Tae, Omitsu fights back when chosen by a sleazy, nouveau riche factory owner who made his money making planes for the navy, and while Tae tries to talk her down Kiku simply sits on her face and tells the man to do his business. Afterwards, Mitsu tries to kill herself and her friendship with Fumi is strained by her internalised sense of shame. Determined to save enough money to redeem Fumi’s contract before the same thing happens to her, she throws herself into sex work and begins to lose Fumi’s respect.

It’s the two girls who see this place as haunted most clearly, firstly in catching sight of Tae wandering the corridors in her nighty on the night of her husband’s murder, and then by Fumi’s belief she has seen the pale ghost of a geisha only to realise it was just a wig on a shelf. Mitsu says it belonged to a woman who contracted syphilis, went mad, and then died, a fate she now fears may also befall her. Like many of the other women, the girls have been sold into sexual slavery by their parents most likely because their families are poor and they can’t feed their other children. This kind of rural poverty is of course exacerbated by the financial demands of imperial expansion while the dehumanising elements of militarism, the belief that everything must be devoted to the war effort, allow this heinous relic of the feudal past to continue. Sons after all belong to the emperor and will become brave soldiers fighting for their nation, while daughters have no intrinsic value other than as wives or sex workers to be advantageously traded or sold on.

It’s this that Fumi comes to realise and resent. She insists that she will never return to her home or parents because at the end of the day, they sold her. Yet she feels little sympathy on learning that one of the other women is a notorious criminal who murdered her foster parents because they too took girls in to sell them on. The hotel somehow becomes the nexus of all this pain and violence, a place the women can never escape. Ito does his best to make clear that this is hell by travelling through the air ducts, on towards the eerie glow of the furnace and the dank passages running under the hotel and out into the sea. The boiler room connects all other areas of the hotel and exposes all their secrets in the sound that travels through the ducts. But some secrets are designed to remain forever hidden until the wrecking balls of the contemporary era force them into the light and confront us with this buried history. Until then, the hotel exists in a ghostly state, Ito flooding it with hazy images and visitations that read as eternal apparitions of this place’s inescapable despair trapping all within its labyrinth of unresolved longing.

Trailer (no subtitles)

At the end of

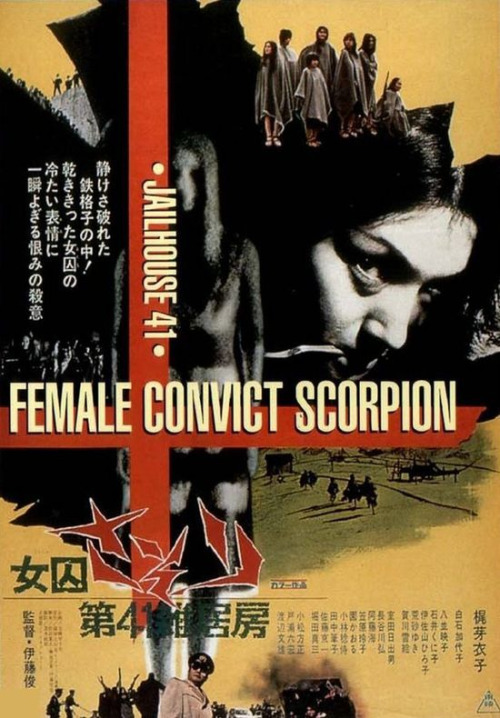

At the end of  Female Prisoner Scorpion: Jailhouse 41 (女囚さそり第41雑居房, Joshu Sasori – Dai 41 Zakkyobo) picks up around a year after the end of

Female Prisoner Scorpion: Jailhouse 41 (女囚さそり第41雑居房, Joshu Sasori – Dai 41 Zakkyobo) picks up around a year after the end of