In the classic yazkua films of old, going to prison for the gang could be a badge of honour and one of the ways you could catapult yourself into the higher ranks. By the 1990s, however, the yakuza is a much depleted force and it seems few are willing to give up years of their lives on a point of honour for an uncertain reward. At least, that’s how it is for most of the gangsters at the centre of Banmei Takahashi’s Neo Chinpira: Zoom Goes the Bullet (ネオ チンピラ 鉄砲玉ぴゅ~, Neo Chinpira: Teppodama Pyu) , a slacker comedy in which a young hanger on faces a dilemma when he’s made the lookout on a squad sent to bump off a rival only for his squamates go to great lengths to injure themselves first so they won’t have to go through with it.

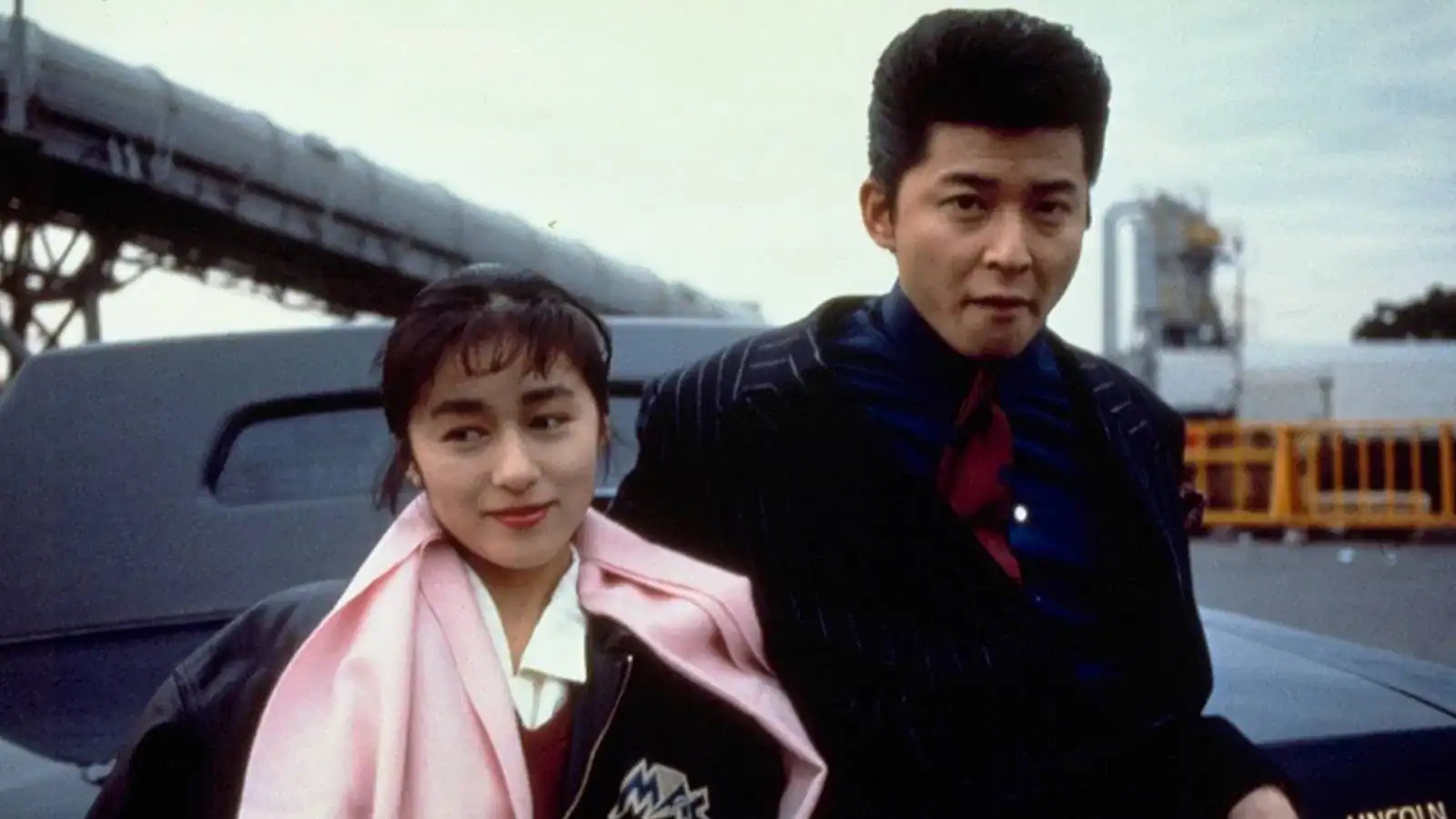

Junko (Sho Aikawa) is an unlikely hero. With a rockabilly quiff and a red jacket, he’s nominally the driver for gangster Yoshikawa (Toru Minegishi) which means he gets to drive his limo and act like a big man for a while making calls on his carphone. But as much as Junko shows off to his girlfriend Noriko, a hostess at a Korean bar, by instructing the landlady not to clear up his empty bottles because they’ll make a good weapon in an emergency, he’s otherwise something of a joke. The limo ends up getting “stolen” by a young woman who just likes American cars and sexually aroused by gunfire.

Even Yumeko (Chikako Aoyama) chuckles that Junko sounds like a girl when he says he wants to see the ocean while they’re driving around. “Junko” is ordinarily a girl’s name. He picked it up as a kind of hazing based on an alternate reading of his name kanji. She says the same thing again when he reveals he’s never brought a girl back to his place before, probably because it’s in a disused building he was given to manage where he’s surrounded by junk like an old barber’s chair and pinball machine while the figure of Humphrey Bogart in the Maltese Falcon looks down at him from a poster as if embodying his unattainable gangster dreams. As masculine icons go, Junko is also plagued by his uncle, Mizuta (Joe Shishido), a legendary gangster and representative of old school yakuza who take the code seriously and wouldn’t put up with people like Junko’s colleagues who engage in “zooming”, deliberately shooting themselves to get out of being ordered to carry out a hit. He’s not overly impressed by Junko either, unable to understand why he’d become an errand boy for a petty gangster rather than be his own boss as a small-time crook.

Junko’s dilemma is whether he’s really up to this task and will be to go through with it or will end up chickening out and injuring himself too. Crows are more cowardly than they seem, Yumeko explains in an obvious allegory for the yakuza. They pick a place and defend it as a group, while their numbers are way up lately so their individual turfs are shrinking. But now Junko’s all on his own and filled with uncertainty not knowing if he can pass this rite of passage and be accorded a man or will forever be trapped in a liminal space of adolescence never to be taken seriously or make any progress in his life. In an effort to toughen up, he swaps his red jacket for a suit and finally puts on a shiny leather overcoat, ripping off the buttons to bind it more tightly around him with the belt as if it were a kind of armour.

Somehow the lighthearted ridiculousness of this world of bumbling yakuza and creepy corrupt cops lends an additional poignancy to Junko’s final gesture as he sets off on his path, not really believing he will return. He doesn’t even wait for the pictures he had taken at a photo booth. They won’t be much use to him where he’s going, but at the same time it’s like he’s treading water never quite getting closer to his destination but continuing along his long sad walk. Banmei Takahashi sticks firmly to his pink film roots, sticking in a weird sex scene at regular intervals as Yumeko becomes enraptured by pistols, but also has quite a lot of fun with his “uncool” gangsters and the lost young man who looks up to them while perhaps knowing that this image of stone cold masculinity only really exists in the movies.

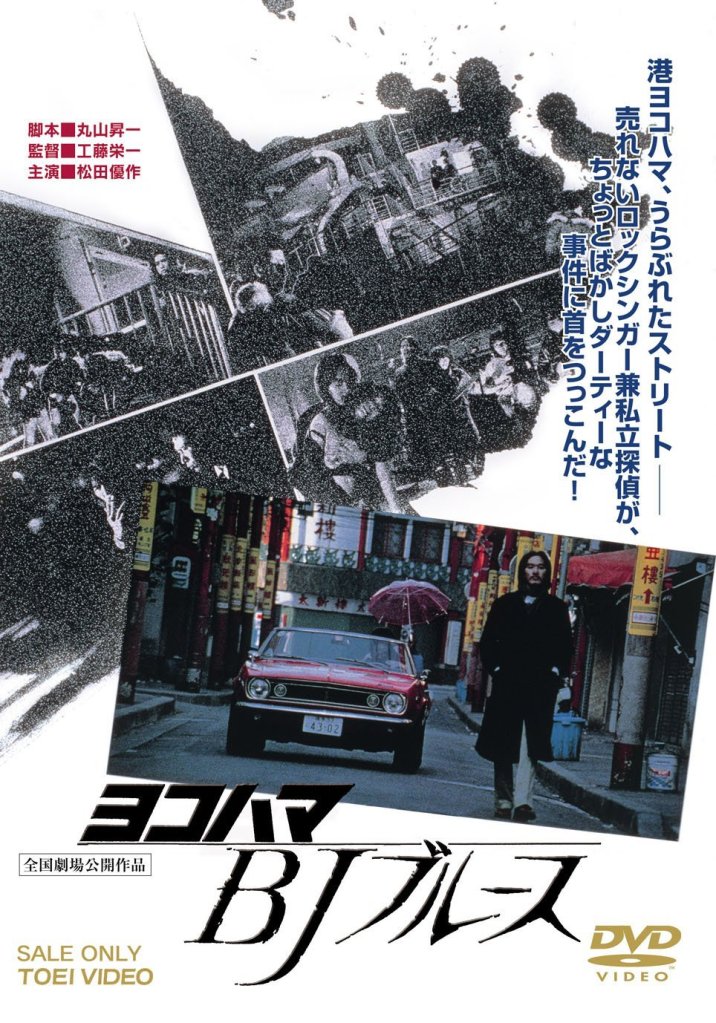

Yusaku Matsuda may have been the coolest action star of the ‘70s but by the end of the decade he was getting bored with his tough guy persona and looked to diversify his range a little further than his recent vehicles had allowed him. Matsuda had already embarked on a singing career some years before but in Eiichi Kudo’s Yokohama BJ Blues (ヨコハマBJブルース), he was finally allowed to display some of his musical talents on screen as a blues singer and ex-cop who makes ends meet through his work as a detective for hire.

Yusaku Matsuda may have been the coolest action star of the ‘70s but by the end of the decade he was getting bored with his tough guy persona and looked to diversify his range a little further than his recent vehicles had allowed him. Matsuda had already embarked on a singing career some years before but in Eiichi Kudo’s Yokohama BJ Blues (ヨコハマBJブルース), he was finally allowed to display some of his musical talents on screen as a blues singer and ex-cop who makes ends meet through his work as a detective for hire.