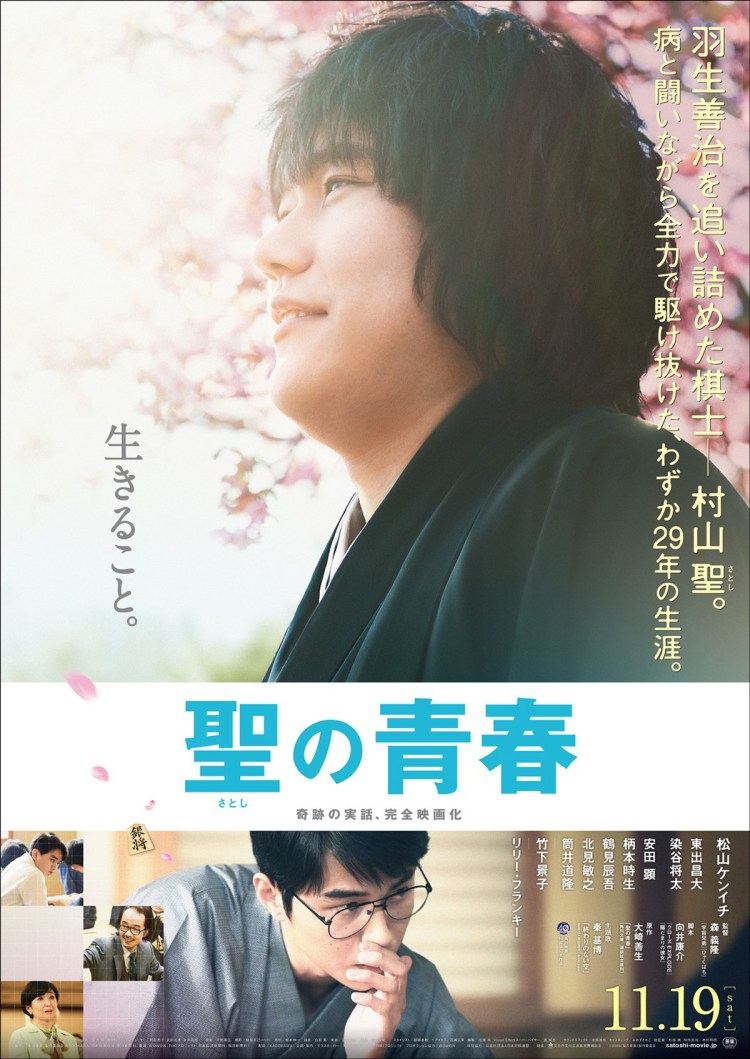

There’s a slight irony in the English title of Yoshitaka Mori’s tragic shogi star biopic, Satoshi: A Move For Tomorrow (聖の青春, Satoshi no Seishun). The Japanese title does something similar with the simple “Satoshi’s Youth” but both undercut the fact that Satoshi (Kenichi Matsuyama) was a man who only ever had his youth and knew there was no future for him to consider. The fact that he devoted his short life to a game that’s all about thinking ahead is another wry irony but one it seems the man himself may have enjoyed. Satoshi Murayama, a household name in Japan, died at only 29 years old after denying chemotherapy treatment for bladder cancer in fear that it would interfere with his thought process and set him back on his quest to conquer the world of shogi. Less a story of triumph over adversity than of noble perseverance, Satoshi lacks the classic underdog beats the odds narrative so central to the sports drama but never quite manages to replace it with something deeper.

There’s a slight irony in the English title of Yoshitaka Mori’s tragic shogi star biopic, Satoshi: A Move For Tomorrow (聖の青春, Satoshi no Seishun). The Japanese title does something similar with the simple “Satoshi’s Youth” but both undercut the fact that Satoshi (Kenichi Matsuyama) was a man who only ever had his youth and knew there was no future for him to consider. The fact that he devoted his short life to a game that’s all about thinking ahead is another wry irony but one it seems the man himself may have enjoyed. Satoshi Murayama, a household name in Japan, died at only 29 years old after denying chemotherapy treatment for bladder cancer in fear that it would interfere with his thought process and set him back on his quest to conquer the world of shogi. Less a story of triumph over adversity than of noble perseverance, Satoshi lacks the classic underdog beats the odds narrative so central to the sports drama but never quite manages to replace it with something deeper.

Diagnosed with nephrotic syndrome as a child, the young Satoshi spent a lot of time alone in hospitals. To ease his boredom his father gave him a shogi set and the boy was hooked. Immersing himself in the world of the game, Satoshi read everything he could about tactics, practiced till his fingers bled and came up with his own unorthodox technique for playing that would eventually take him from his Osaka home to the bright lights of Tokyo. Determined to become the “Meijin”, beat top shogi player Habu (Masahiro Higashide), and get into the coveted 9th Dan ranking Satoshi cares for nothing other than the game, his only other hobbies being drink, junk food, and shojo manga.

Undoubtedly brilliant yet difficult, Satoshi is not an easy man to get along with. Years of medical treatment for nephrosis have left him pudgy and bloated, and an aversion to cutting his hair and nails (poignantly insisting that they have a right to live and grow) already makes him an unusual presence at the edge of a shogi board. He’s not exactly charming either with his overwhelming intensity, aloofness, and fits of angry frustration. Yet the shogi world fell in love with him for his encyclopaedic yet totally original approach to the game. His friends, of which there many, were willing to overlook his eccentricities because of his immense skill and because they knew that his anger and impatience came from forever knowing that his time was limited and much of life was already denied to him.

This insistent devotion to the game and desire to scale its heights before it’s too late is what gives Satoshi its essential drive even if the road does not take us along the usual route. Reckless with his health despite, or perhaps because of, his knowledge of his weakness, Satoshi operates on a self destructive level of excessive drink and poor diet though when he starts experiencing more serious problems which require urgent medical intervention, it’s easy to see why he would be reluctant to get involved with even more doctors. Eventually diagnosed with bladder cancer, Satoshi at first refuses and then delays treatment in fear that it will muddy his mind but the doctors tell him something worse – he should stay away from shogi and the inevitable stress and strain it places both on body and mind. For Satoshi, life without shogi is not so different from death.

Satoshi has his sights set on taking down popular rival Habu whose fame has catapulted him into the Japanese celebrity pantheon, even marrying a one of the most beloved idols of the day. Habu is the exact opposite of Satoshi – well groomed, nervous, and introverted but the two eventually develop a touching friendship based on mutual admiration and love of the game. On realising he may be about to beat Satoshi and crush his lifelong dreams, Habu is visibly pained but it would be a disservice both to the game and to Satoshi not to follow through. Outside of shogi the pair have nothing in common as an attempt to bond over dinner makes clear but Habu becomes the one person Satoshi can really talk to about his sadness in the knowledge that he’ll never marry or have children. As different as they are, Satoshi and Habu are two men who see the world in a similar way and each have an instinctual recognition of the other which gives their rivalry a poignant, affectionate quality.

Despite the game’s stateliness, Mori manages to keep the tension high as elegantly dressed men face each other across tiny tables slapping down little pieces of wood featuring unfamiliar symbols. Japanese viewers will of course be familiar with the game though overseas audiences may struggle with some its nuances even if not strictly necessary to enjoy the ongoing action. Matsuyama gives a standout performance as the tortured, tragic lead even gaining a huge amount of weight to reflect Satoshi’s famously pudgy appearance. Rather than the story of a man beating the odds, Satoshi’s is one of a man who fought a hard battle with improbable chances of success but never gave up, sacrificing all of himself in service of his goal. Genuinely affecting yet perhaps gently melancholy, Satoshi: A Move for Tomorrow is a tribute to those who are prepared to give all of themselves yet also a reminder that there is always a price for such reckless disregard of self.

Satoshi: A Move for Tomorrow was screened as part of the Udine Far East Film Festival 2017.

Original trailer (English subtitles)

There are few things in life which cannot at least be improved by a full and frank apology. Sometimes that apology will need to go beyond a simple, if heart felt, “I’m Sorry” to truly make amends but as long as there’s a genuine desire to make things right, it can be done. Some people do, however, need help in navigating this complex series of culturally defined rituals which is where the enterprising hero of Nobuo Mizuta’s The Apology King (謝罪の王様, Shazai no Ousama), Ryoro Kurojima (Sadao Abe), comes in. As head of the Tokyo Apology Centre, Kurojima is on hand to save the needy who find themselves requiring extrication from all kinds of sticky situations such as accidentally getting sold into prostitution by the yakuza or causing small diplomatic incidents with a tiny yet very angry foreign country.

There are few things in life which cannot at least be improved by a full and frank apology. Sometimes that apology will need to go beyond a simple, if heart felt, “I’m Sorry” to truly make amends but as long as there’s a genuine desire to make things right, it can be done. Some people do, however, need help in navigating this complex series of culturally defined rituals which is where the enterprising hero of Nobuo Mizuta’s The Apology King (謝罪の王様, Shazai no Ousama), Ryoro Kurojima (Sadao Abe), comes in. As head of the Tokyo Apology Centre, Kurojima is on hand to save the needy who find themselves requiring extrication from all kinds of sticky situations such as accidentally getting sold into prostitution by the yakuza or causing small diplomatic incidents with a tiny yet very angry foreign country. No names, no strings. That’s the idea at the centre of Daisuke Miura’s adaptation of his own stage play, Love’s Whirlpool (愛の渦, Koi no Uzu). Love is an odd word here as it’s the one thing that isn’t allowed to exist in this purpose built safe space where like minded people can come together to experience the one thing they all crave – anonymous sex. From midnight to 5am this group of four guys and four girls have total freedom to indulge themselves with total discretion guaranteed.

No names, no strings. That’s the idea at the centre of Daisuke Miura’s adaptation of his own stage play, Love’s Whirlpool (愛の渦, Koi no Uzu). Love is an odd word here as it’s the one thing that isn’t allowed to exist in this purpose built safe space where like minded people can come together to experience the one thing they all crave – anonymous sex. From midnight to 5am this group of four guys and four girls have total freedom to indulge themselves with total discretion guaranteed. When a crime has been committed, it’s important to remember that there may be secondary victims whose lives will be destroyed even if they themselves had no direct involvement in the case itself. This is even more true in the tragic case that person who is responsible is themselves a child with parents and siblings still intent on looking forward to a life that their son or daughter will now never lead. This isn’t to place them on the same level as bereaved relatives, but simply to point out the killer’s family have also lost a child who they have every right to grieve for, though their grief will also be tinged with guilt and shame.

When a crime has been committed, it’s important to remember that there may be secondary victims whose lives will be destroyed even if they themselves had no direct involvement in the case itself. This is even more true in the tragic case that person who is responsible is themselves a child with parents and siblings still intent on looking forward to a life that their son or daughter will now never lead. This isn’t to place them on the same level as bereaved relatives, but simply to point out the killer’s family have also lost a child who they have every right to grieve for, though their grief will also be tinged with guilt and shame. Back in 2008 as the financial crisis took hold, a left leaning early Showa novel from Takiji Kobayashi, Kanikosen (蟹工船), became a surprise best seller following an advertising campaign which linked the struggles of its historical proletarian workers with the put upon working classes of the day. The book had previously been adapted for the screen in 1953 in a version directed by So Yamamura but bolstered by its unexpected resurgence, another adaptation directed by SABU arrived in 2009.

Back in 2008 as the financial crisis took hold, a left leaning early Showa novel from Takiji Kobayashi, Kanikosen (蟹工船), became a surprise best seller following an advertising campaign which linked the struggles of its historical proletarian workers with the put upon working classes of the day. The book had previously been adapted for the screen in 1953 in a version directed by So Yamamura but bolstered by its unexpected resurgence, another adaptation directed by SABU arrived in 2009. Yaro Abe’s manga Midnight Diner (深夜食堂, Shinya Shokudo) was first adapted as 10 episode TV drama back in 2009 with a second series in 2011 and a third in 2014. With a Korean adaptation in between, the series now finds itself back for second helpings in the form of a big screen adaptation.

Yaro Abe’s manga Midnight Diner (深夜食堂, Shinya Shokudo) was first adapted as 10 episode TV drama back in 2009 with a second series in 2011 and a third in 2014. With a Korean adaptation in between, the series now finds itself back for second helpings in the form of a big screen adaptation.