“No one knows what will happen to us in this world of illusion” muses a conflicted villain in Tomu Uchida’s seminal proto-procedural, Policeman (警察官, Keisatsukan, AKA Police Officer). Forever an enigma, Uchida had made his name through a series of broadly progressive, left-wing films featuring strong social critique, yet he also made this mildly authoritarian, overtly pro-police piece of militarist propaganda long before it became necessary to do so. But then, look a little closer and you’ll find him subtly undercutting the messaging, reconfiguring his tale of a courageous policeman who sets aside his personal feelings in the pursuit of justice as one of tragedy in which a man ultimately imprisons himself by doing so.

The hero, earnest policeman Itami (Isamu Kosugi), was once as he later reveals a wayward young man. “The world was against me, I thought. I was young then” he sighs, explaining that he owes his life to his boss and mentor, Sgt. Miyabe (Taisuke Matsumoto), who became a second father and set him on the right path which he now of course follows. His long lost childhood friend Tetsuo (Eiji Nakano), with whom he reconnects during a routine vehicle check, apparently experienced something similar having fallen out with his wealthy industrialist father but claims that he’s become an elite layabout spending all his time at the golf course and asking his dad for money every time he runs out which seems nothing if not contradictory but then familial relationships can be complex. In any case, a repeated motif sees the two men taking diverging paths, literally, the implication being that they’ve each chosen different directions in response in to the same adolescent crisis when in a sense “orphaned” through parental disconnection.

On hearing Tetsuo’s story, Itami asks him with thinly veiled horror if he hasn’t become a communist, that being a fairly common and fashionable way for a young man from a wealthy family to fall out with his father. Tetsuo laughs it off, wishing it were political but claiming somewhat vaguely that it was a matter of feeling. The exchange is revealing in that screenwriter Eizo Yamauchi had apparently been instructed to portray the criminal gang at the film’s centre, of which Tetsuo is later revealed to be a member, as “communist” though no political ideology or identity is ever directly stated. Nevertheless, the central drama is clearly inspired by the Omori Bank Robbery (1932) in which a three members of the Communist Party robbed the Kawasaki Daiichi Bank without the knowledge or authority of party officials in order to gain funding for the movement. The incident backfired, badly discrediting the Communist Party (illegal at the time) and thereby imploding the most viable source of opposition to rising militarism. Armed bank robbery not being a common occurrence in Japan, most viewers would necessarily associate this brand of criminality with “communism”, killing two birds with one stone as the film does its intended job of making the world seem more dangerous than it is while reinforcing an authoritarian message that the police will protect.

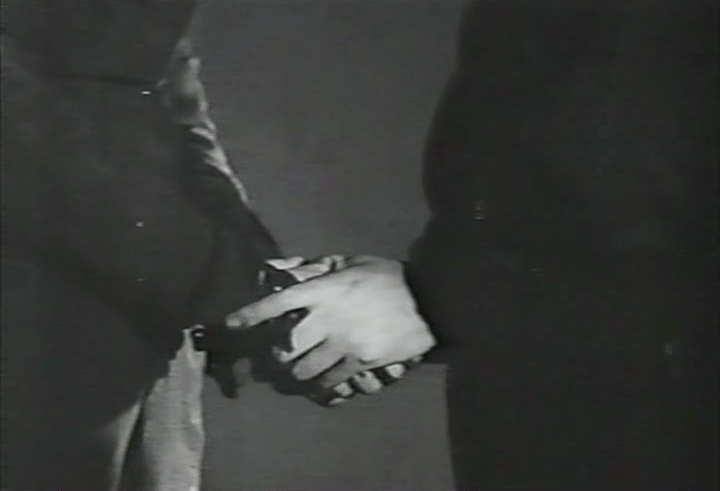

Yet, on the other hand, perhaps it really was “feeling” after all. The relationship between the two men has an intensely homoerotic quality with frequent flashbacks to their carefree high school days during which they read each other romantic German poetry, played rugby, and frolicked on a beach in the company of a very large dog. Itami largely ignores his potential love interest in Miyabe’s pretty daughter, save for briefly thinking about her while on a three-day stakeout of the robbers’ den, while constantly chasing Tetsuo after becoming suspicious that he may be the man responsible for shooting Miyabe and fleeing the scene after a robbery. His inner torment lies partly in the conflict between his responsibilities to friendship and the law, but also perhaps in his unresolved feelings for Tetsuo. Driven half out of his mind, his final epiphany crying out “I am a policeman” is as much a rejection of an identity as a claiming of one, entirely sublimating himself within the image of the role that he has chosen to play in society shedding his personal feeling and desires as he does so. In “saving” Tetsuo, shooting him in the hand to prevent his suicide, tenderly cuffing and then embracing him, he evokes both a sense of return and forgiveness and another of goodbye further enhanced by the abruptness of the transition which follows.

Taken in this light, the late and extremely jarring slide into overt propaganda through a series of title cards loudly proclaiming the virtue of the police takes on a differing kind of anxiety in its authoritarian dimensions as a force which destroys rather than protects in its capacity to erase individual identity. Nevertheless, Uchida also includes numerous shots of heroic policemen in their dashing uniforms as they assemble for drill or show up en masse on their bikes ready to fight crime. Tetsuo’s final appearance, meanwhile, is extremely sinister dressed as he is in an outfit which would later become associated with fascism, his meticulous uniformity in strong contrast to the then crazed and dishevelled Itami still in his crumpled kimono with messy hair and three days’ worth of beard growth from his stakeout. Yet there’s nothing but pain and fear in his eyes as he realises that his friend has seen through him, Itami rather ostentatiously bundling Tetsuo’s lighter into a handkerchief almost as if he meant to him let know.

Shooting mainly on location, Uchida’s camera is rarely at rest even employing a series of complicated vehicle tracking shots one of which eventually resolves itself into a first person perspective while the final sequence is tense in the extreme with its gunfire, search lights, and complex choreography. His use of flashback is precise and unusual, far ahead of its time in its acuity as if we actually see Itami’s thought process on screen jumping from one idea to another, while the meeting of the two men on the desolate docks seems to be drenched in loneliness and a sense of futility even while free of the oppressive shadows from the buildings which seemed to dwarf them in the city. Somehow desperately sad despite the catharsis of its final scene, Policeman subtly implies there might not be much difference between hero and villain, or between communist and militarist, save walking one way and not another as two men find their friendship frustrated by time and circumstance coming together only to be driven apart.