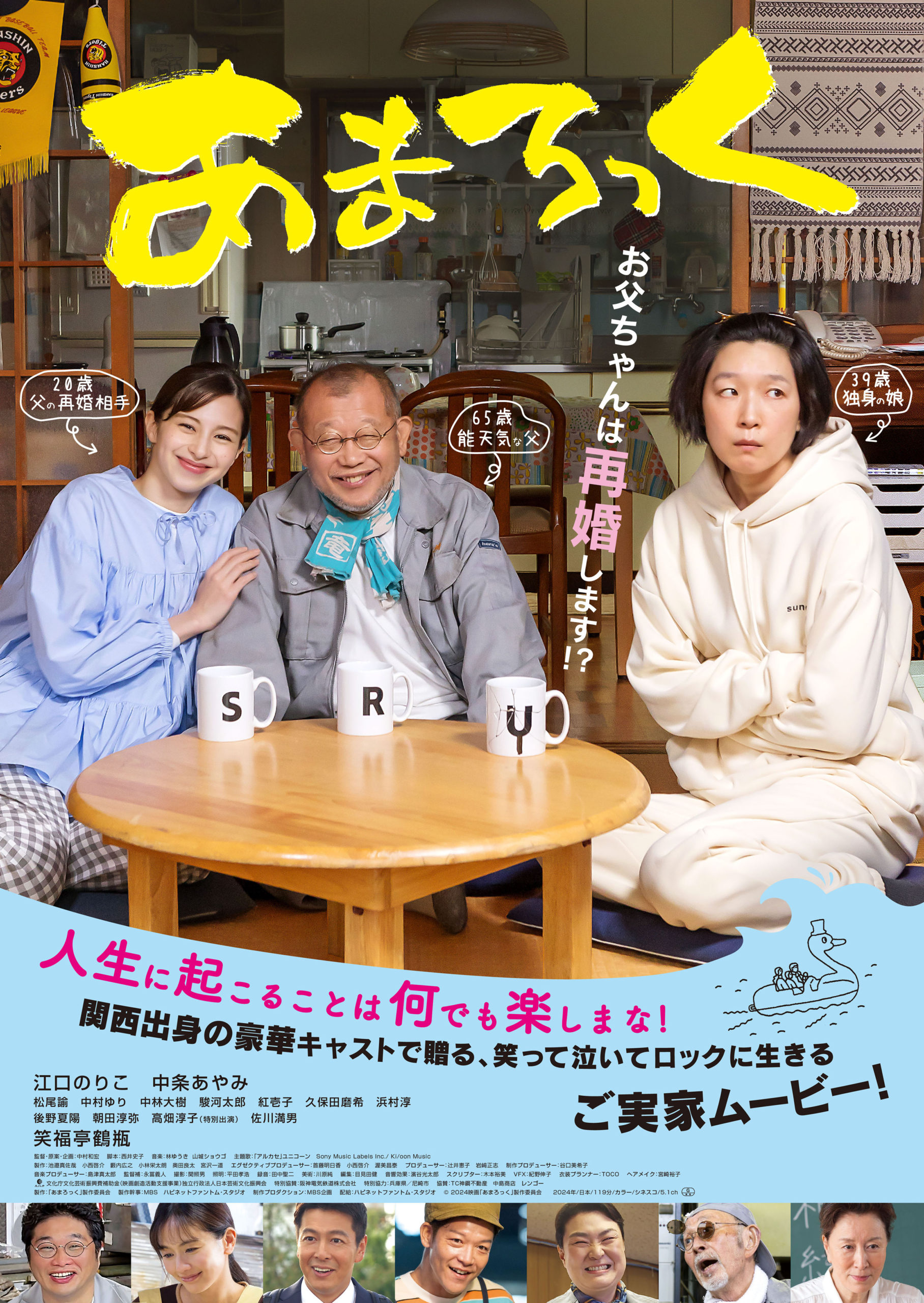

The purpose of a lock, at least far as those on water are concerned, is to keep everything on an even keel and protect the surrounding area from flooding. From the lock’s point of view it might be a thankless task, people never notice you’re there unless you’ve somehow failed at your job but the lock is ever present and always about its duty even if it might be difficult to understand. For all of these reasons, the heroine of Kazuhiro Nakamura’s gentle indie drama had come to think of her father as the titular Amalock (あまろっく) but often resented him for it, seeing him only as lazy and irresponsible.

For Ryutaro (Tsurube Shofukutei), meanwhile, laughter was the only way to make life bearable. His motto was to always enjoy the things that happen in life be they good or bad which is why he puts out a congratulations sign when his grown up daughter Yuko (Noriko Eguchi) returns home after being made redundant. Despite being good at her job and in receipt of several commendations for her work, Yuko is simply not pleasant to be around and creates tension in the office with her grumpy aloofness and tendency to make younger male members of staff cry in front of her.

The implication is that Yuko became the exact opposite of the father she thought was feckless and of no use to anyone, yet mainly finds herself lying in front of the TV in a tracksuit mainlining snacks exactly as he had done when she was a child. Seemingly trapped in an intense depression, she makes no attempt to find new work for eight years, instead being supported by her father’s moribund ironmongers. The surprise news that he plans to remarry 20 years after her mother’s death to a woman barely 20 who works at the townhall sends shockwaves through her life and turns her into a petulant, resentful teenager who can’t accept her new stepmother.

The situation is of course ridiculous. Yuko is almost 40 and Saki (Ayami Nakajo), Ryutaro’s new wife, makes no attempt to wield authority over her beyond the well-meaning attempts to introduce potential husbands more because she thinks it would be nice for her to have someone than she wants her out of the house. Even so, Yuko’s problem is that she can’t understand the way her father works and that his cheerful attitude to life has value to those around him who are buoyed up by his friendliness and easy going nature even when times are hard. Like the Amalock, he’s always been there quietly supporting her despite her scorn and resentment, preventing her from becoming overwhelmed by the floodwaters of life tragedies.

In his way, he’s done something similar for Saki who ironically only ever wanted what Yuko could have had in a happy “harmonious” family having experienced a series of troubles of her own. Saki honours Yuko’s mother’s memory and includes it in her vision of the “family,” but struggles to get through to Yuko who remains difficult and resentful unable to see the value in the kind of life that Saki wants or in herself as human who might benefit more from interacting with others. The twin stressors of unexpected tragedy and a tentative marriage proposal from a man who turned out to know her little better than she thought begin to shift her perspective allowing her to see what it really was her father brought to the world and what she might bring to it too if only she were less serious about things that don’t really matter.

That is after all how you find your way to a harmonious life, becoming an Amalock for others who can also be an Amalock for you and might be willing to make a few compromises to make that happen. Set in the tranquil town of Amagasaki, Nakamura’s gentle tale captures a little of life’s absurdities along with the simple power of good humour to make life easier to bear. Rooted in tragedy as it may be, Ryutaro’s philosophy of making life a celebration has its merits and ones which are not lost on a newly enlightened Yuko becoming more and more like her father but also like herself at the heart of a harmonious family.

Amalock screened as part of this year’s Osaka Asian Film Festival.

Original trailer (no subtitles)

Prolific as he is, veteran director Yoji Yamada (or perhaps his frequent screenwriter in recent years Emiko Hiramatsu) clearly takes pleasure in selecting film titles but What a Wonderful Family! (家族はつらいよ, Kazoku wa Tsurai yo) takes things one step further by referencing Yamada’s own long running film series Otoko wa Tsurai yo (better known as Tora-san). Stepping back into the realms of comedy, Yamada brings a little of that Tora-san warmth with him for a wry look at the contemporary Japanese family with all of its classic and universal aspects both good and bad even as it finds itself undergoing number of social changes.

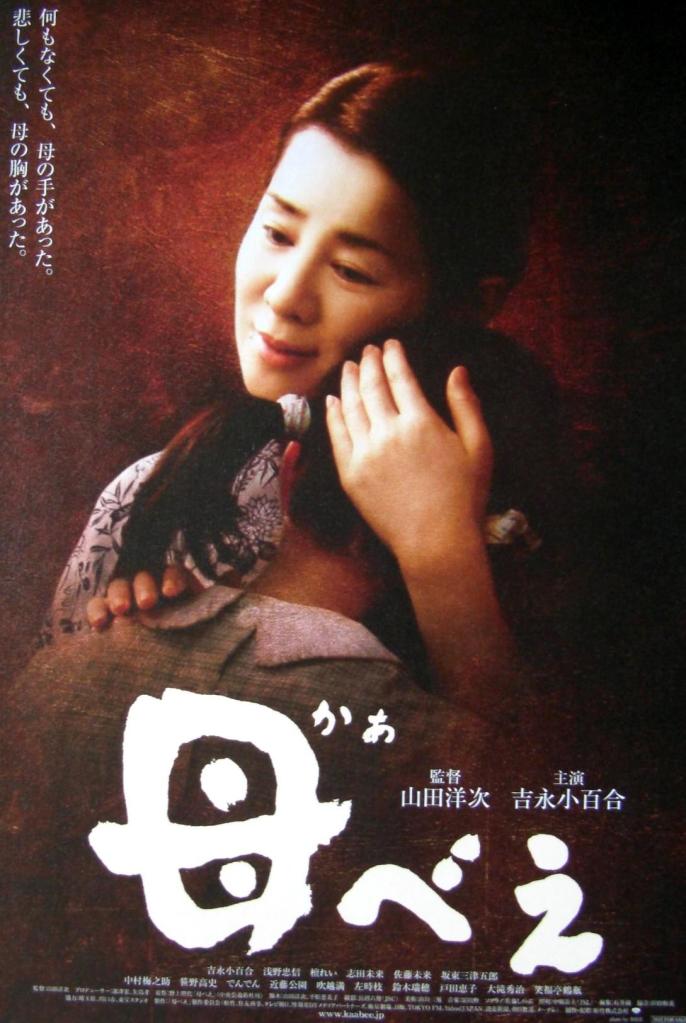

Prolific as he is, veteran director Yoji Yamada (or perhaps his frequent screenwriter in recent years Emiko Hiramatsu) clearly takes pleasure in selecting film titles but What a Wonderful Family! (家族はつらいよ, Kazoku wa Tsurai yo) takes things one step further by referencing Yamada’s own long running film series Otoko wa Tsurai yo (better known as Tora-san). Stepping back into the realms of comedy, Yamada brings a little of that Tora-san warmth with him for a wry look at the contemporary Japanese family with all of its classic and universal aspects both good and bad even as it finds itself undergoing number of social changes. Yoji Yamada’s films have an almost Pavlovian effect in that they send even the most hard hearted of viewers out for tissues even before the title screen has landed. Kabei (母べえ), based on the real life memoirs of script supervisor and frequent Kurosawa collaborator Teruyo Nogami, is a scathing indictment of war, militarism and the madness of nationalist fervour masquerading as a “hahamono”. As such it is engineered to break the hearts of the world, both in its tale of a self sacrificing mother slowly losing everything through no fault of her own but still doing her best for her daughters, and in the crushing inevitably of its ever increasing tragedy.

Yoji Yamada’s films have an almost Pavlovian effect in that they send even the most hard hearted of viewers out for tissues even before the title screen has landed. Kabei (母べえ), based on the real life memoirs of script supervisor and frequent Kurosawa collaborator Teruyo Nogami, is a scathing indictment of war, militarism and the madness of nationalist fervour masquerading as a “hahamono”. As such it is engineered to break the hearts of the world, both in its tale of a self sacrificing mother slowly losing everything through no fault of her own but still doing her best for her daughters, and in the crushing inevitably of its ever increasing tragedy.