Jimmy and Cherie, against all the odds, are still together and in a happy longterm relationship in the third addition to Pang Ho-cheung’s series of charming romantic comedies, Love off the Cuff (春嬌救志明). Following the dramatic declaration at the end of Love in the Buff, the pair have continued to grow into each other embracing each of their respective faults but after all this time Jimmy and Cherie have to make another decision – stay together forever or call it quits for good.

Jimmy and Cherie, against all the odds, are still together and in a happy longterm relationship in the third addition to Pang Ho-cheung’s series of charming romantic comedies, Love off the Cuff (春嬌救志明). Following the dramatic declaration at the end of Love in the Buff, the pair have continued to grow into each other embracing each of their respective faults but after all this time Jimmy and Cherie have to make another decision – stay together forever or call it quits for good.

The major drama this time around occurs with the looming spectre of parenthood as Cherie’s long absent father and Jimmy’s “godmother” suddenly arrive to place undue strain on the couple’s relationship. These unexpected twin arrivals do their best to push Cherie’s buttons as she’s forced to re-examine her father’s part in her life (or lack of it) and how he may or may not be reflected in her choice of Jimmy, whilst Jimmy’s Canadian “godmother” makes a request of him in that he be the father of her child. Jimmy, a self confessed child himself, does not want anything to with this request but is too cowardly to hurt the feelings of a childhood friend and is hoping Cherie will do it for him. Cherie is wise to his game and doesn’t want to be trotted out as his old battle axe of a spouse but at 40 years of age children is one of the things she needs to make a decision on, another being whether she wants them with Jimmy.

Cherie’s father was an unhappy womaniser who eventually abandoned the family and has had little to do with any of them ever since. In his sudden return he brings great news! He’s getting married, to a woman much younger than Cherie. Building on the extreme insecurities and trust issues Cherie has displayed throughout the series, her faith in Jimmy crumbles especially after she intercepts some interestingly worded (yet totally innocent) text messages on his phone which turn out to relate to an unfortunate incident with their dog. Jimmy’s reliability continues to be one of his weaker elements as the behaviour he sees as pragmatic often strikes Cherie as self-centered or insensitive. Things come to a head during a disastrous getaway to Taipei in which the couple are caught in an earthquake. Cherie freezes and cowers by the door while Jimmy ties to guide her to safety but his efforts leave her feeling as if he will never value anything more than he does himself.

Moving away from the gentle whimsy of Love in a Puff, Cuff veers towards the surreal as the pair end up in ever stranger, yet familiar, adventures including a UFO spotting session which goes horribly wrong landing them with community service and accidental internet fame. A real life alien encounter becomes the catalyst for the couple’s eventual romantic destiny as does another of Jimmy’s grand gestures enlisting the efforts of Cherie’s father to help him win back his true love. Cherie’s troupe of loyal girlfriends even indulge in some top quality song and dance moves in an effort to cheer her up when it’s looking like she’s hit rock bottom though, improbably enough, it’s Yatterman who eventually saves the day.

Supporting cast is less disparate this time around relying heavily on Cherie’s dad and Jimmy’s godmother but Cherie’s friends get their fare share of screentime even if Jimmy’s seem to fade into the background. Cherie never seems to notice but one of her friends is in love with her and is not invested in her relationship with Jimmy, constantly trying to get her to come away on vacation to a nostalgic childhood destination, but most of the girls seem to be in the dump camp anyhow loyally making sure Cherie thinks as little about Jimmy as is possible lest she eventually go back to him.

Trolling the audience once again with the lengthiest of his horror movie openings (so long you might wonder if you’ve wandered into the wrong screen), Pang begins as he means to go on, mixing whimsical everyday moments of hilarity with surreal set pieces. It’s clear both Jimmy and Cherie have grown throughout the series – no longer does Jimmy skip out on family dinners with Cherie’s mother and brother but patiently helps his (future?) mother-in-law figure out her smartphone as well as becoming something like her errant father’s wingman. Things wrap up in the predictable fashion but it does leave us primed for the inevitable sequel – Love up the Duff? Could be, it’s the next logical step after all.

Love off the Cuff was screened at the 19th Udine Far East Film Festival.

Original trailer (Cantonese with Traditional Chinese/English subtitles)

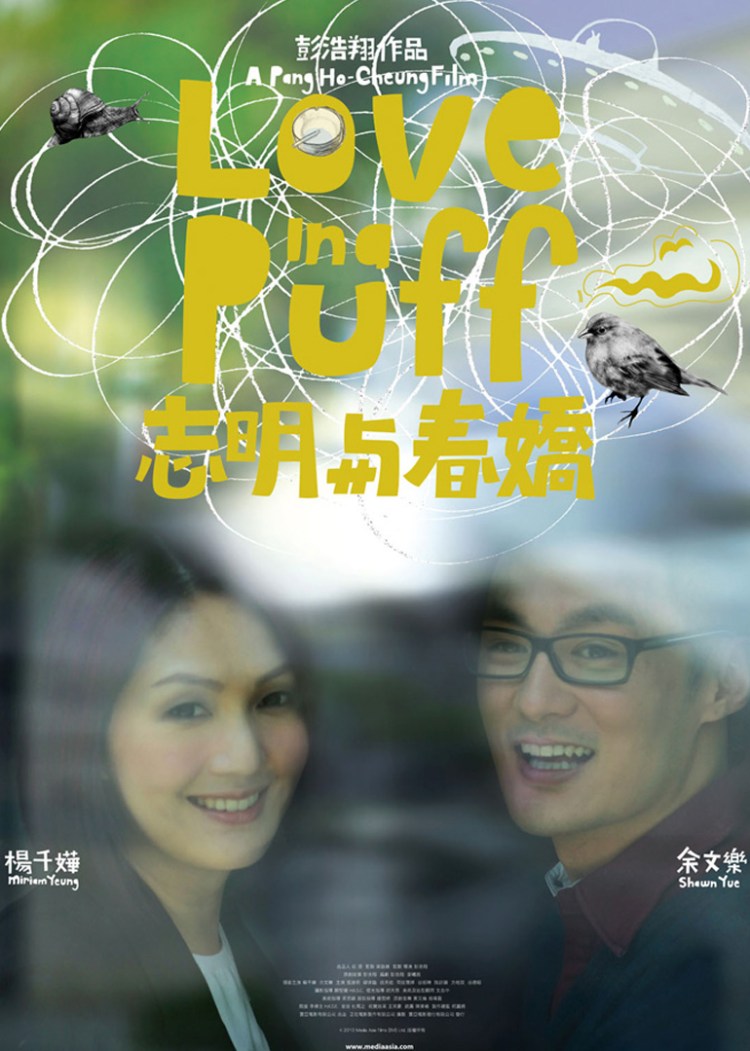

Smokers. Is there a more maligned, ostracised group in the modern world? Considering the rapid pace at which their “harmless” pastime has become unacceptable, you can understand why they might feel particularly put out – literally, as they find themselves taking refuge in designated smoking areas or perhaps back allies where it seems no one’s looking. For all the nostalgia about how easy it was to strike up a friendship with a stranger just by asking for a light, it is also important to remember that smoking is not so “harmless” after all and there are reasons why smokers are asked to keep their activities amongst those who’ve also decided to ignore the warnings. The Smoking Ordinance, oddly enough, may have accidentally boosted the social potential of a smoke as those eager for a puff are given additional reasons to spend time together in an enclosed space, building a sense of community through nicotine addiction.

Smokers. Is there a more maligned, ostracised group in the modern world? Considering the rapid pace at which their “harmless” pastime has become unacceptable, you can understand why they might feel particularly put out – literally, as they find themselves taking refuge in designated smoking areas or perhaps back allies where it seems no one’s looking. For all the nostalgia about how easy it was to strike up a friendship with a stranger just by asking for a light, it is also important to remember that smoking is not so “harmless” after all and there are reasons why smokers are asked to keep their activities amongst those who’ve also decided to ignore the warnings. The Smoking Ordinance, oddly enough, may have accidentally boosted the social potential of a smoke as those eager for a puff are given additional reasons to spend time together in an enclosed space, building a sense of community through nicotine addiction.

Recent Hong Kong action cinema has not exactly been known for its hero cops. Most often, one brave and valiant officer stands up for justice when all around him are corrupt or acting in self interest rather than for the good of the people. Shock Wave (拆彈專家) sees Herman Yau reteam with veteran actor Andy Lau turning in another fine action performance at 55 years of age as a dedicated, highly skilled and righteous bomb disposal officer who becomes the target of a mad bomber after blowing his cover in an undercover operation. These are universally good cops fighting an insane terrorist whose intense desire for revenge and familial reunion is primed to reduce Hong Kong’s central infrastructure to a smoking mess.

Recent Hong Kong action cinema has not exactly been known for its hero cops. Most often, one brave and valiant officer stands up for justice when all around him are corrupt or acting in self interest rather than for the good of the people. Shock Wave (拆彈專家) sees Herman Yau reteam with veteran actor Andy Lau turning in another fine action performance at 55 years of age as a dedicated, highly skilled and righteous bomb disposal officer who becomes the target of a mad bomber after blowing his cover in an undercover operation. These are universally good cops fighting an insane terrorist whose intense desire for revenge and familial reunion is primed to reduce Hong Kong’s central infrastructure to a smoking mess.

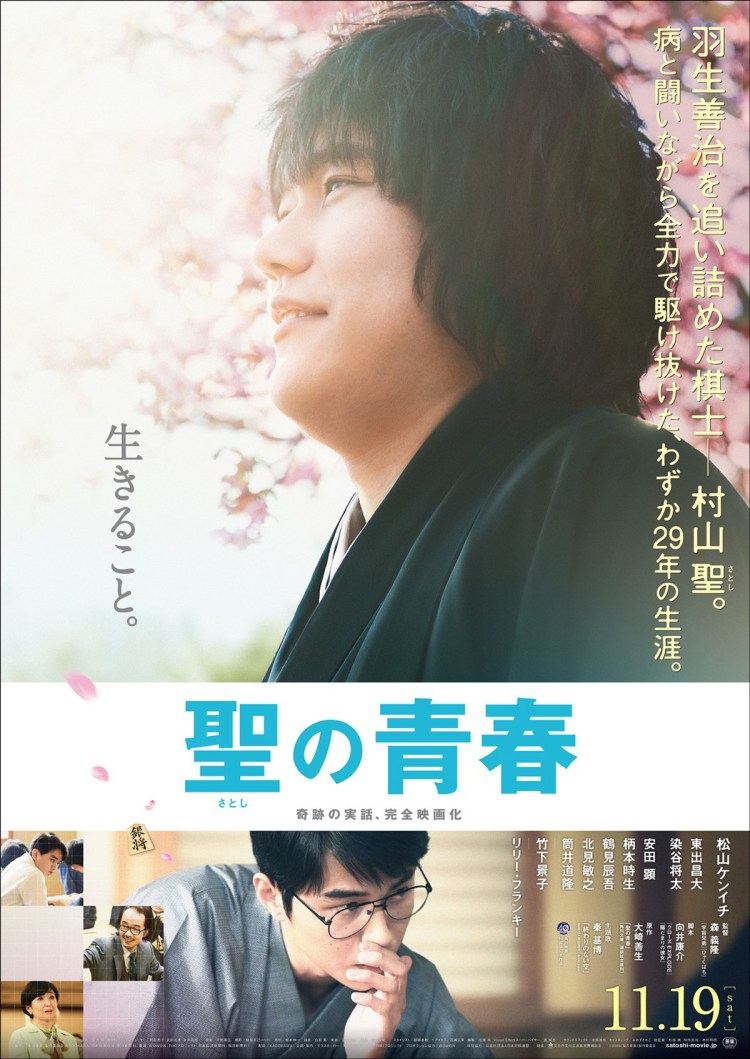

There’s a slight irony in the English title of Yoshitaka Mori’s tragic shogi star biopic, Satoshi: A Move For Tomorrow (聖の青春, Satoshi no Seishun). The Japanese title does something similar with the simple “Satoshi’s Youth” but both undercut the fact that Satoshi (Kenichi Matsuyama) was a man who only ever had his youth and knew there was no future for him to consider. The fact that he devoted his short life to a game that’s all about thinking ahead is another wry irony but one it seems the man himself may have enjoyed. Satoshi Murayama, a household name in Japan, died at only 29 years old after denying chemotherapy treatment for bladder cancer in fear that it would interfere with his thought process and set him back on his quest to conquer the world of shogi. Less a story of triumph over adversity than of noble perseverance, Satoshi lacks the classic underdog beats the odds narrative so central to the sports drama but never quite manages to replace it with something deeper.

There’s a slight irony in the English title of Yoshitaka Mori’s tragic shogi star biopic, Satoshi: A Move For Tomorrow (聖の青春, Satoshi no Seishun). The Japanese title does something similar with the simple “Satoshi’s Youth” but both undercut the fact that Satoshi (Kenichi Matsuyama) was a man who only ever had his youth and knew there was no future for him to consider. The fact that he devoted his short life to a game that’s all about thinking ahead is another wry irony but one it seems the man himself may have enjoyed. Satoshi Murayama, a household name in Japan, died at only 29 years old after denying chemotherapy treatment for bladder cancer in fear that it would interfere with his thought process and set him back on his quest to conquer the world of shogi. Less a story of triumph over adversity than of noble perseverance, Satoshi lacks the classic underdog beats the odds narrative so central to the sports drama but never quite manages to replace it with something deeper. Every keen dramatist knows the most exciting things which happen at a party are always those which occur away from the main action. Lonely cigarette breaks and kitchen conversations give rise to the most unexpected of events as those desperately trying to escape the party atmosphere accidentally let their guard down in their sudden relief. Adapting his own stage play titled Trois Grotesque, Kenji Yamauchi takes this idea to its natural conclusion in At the Terrace (テラスにて, Terrace Nite) setting the entirety of the action on the rear terraced area of an elegant European-style villa shortly after the majority of guests have departed following a business themed dinner party. This farcical comedy of manners neatly sends up the various layers of propriety and the difficulty of maintaining strict social codes amongst a group of intimate strangers, lending a Japanese twist to a well honed European tradition.

Every keen dramatist knows the most exciting things which happen at a party are always those which occur away from the main action. Lonely cigarette breaks and kitchen conversations give rise to the most unexpected of events as those desperately trying to escape the party atmosphere accidentally let their guard down in their sudden relief. Adapting his own stage play titled Trois Grotesque, Kenji Yamauchi takes this idea to its natural conclusion in At the Terrace (テラスにて, Terrace Nite) setting the entirety of the action on the rear terraced area of an elegant European-style villa shortly after the majority of guests have departed following a business themed dinner party. This farcical comedy of manners neatly sends up the various layers of propriety and the difficulty of maintaining strict social codes amongst a group of intimate strangers, lending a Japanese twist to a well honed European tradition.

Nobuhiro Yamashita may be best known for his laid-back slacker comedies, but he’s no stranger to the darker sides of humanity as evidenced in the oddly hopeful Drudgery Train or the heartbreaking exploration of misplaced trust and disillusionment of My Back Page. One of three films inspired by Hakodate native novelist Yasushi Sato (the other two being Kazuyoshi Kumakiri’s Sketches of Kaitan City and Mipo O’s The Light Shines Only There), Over the Fence (オーバー・フェンス) may be among the less pessimistic adaptations of the author’s work though its cast of lonely lost souls is certainly worthy both of Yamashita’s more melancholy aspects and Sato’s deeply felt despair.

Nobuhiro Yamashita may be best known for his laid-back slacker comedies, but he’s no stranger to the darker sides of humanity as evidenced in the oddly hopeful Drudgery Train or the heartbreaking exploration of misplaced trust and disillusionment of My Back Page. One of three films inspired by Hakodate native novelist Yasushi Sato (the other two being Kazuyoshi Kumakiri’s Sketches of Kaitan City and Mipo O’s The Light Shines Only There), Over the Fence (オーバー・フェンス) may be among the less pessimistic adaptations of the author’s work though its cast of lonely lost souls is certainly worthy both of Yamashita’s more melancholy aspects and Sato’s deeply felt despair. Crazy uncles – the gift that keeps on giving. Following the darker edged Over the Fence as the second of two films released in 2016, Nobuhiro Yamashita’s My Uncle (ぼくのおじさん, Boku no Ojisan) pushes his subtle humour in a much more overt direction with a comic tale of a self obsessed (not quite) professor as seen seen through the eyes of his exasperated nephew. “Travels with my uncle” of a kind, Yamashita’s latest is a pleasantly old fashioned comedy spiced with oddly poignant moments as a wiser than his years nephew attempts to help his continually befuddled uncle navigate the difficulties of unexpected romance.

Crazy uncles – the gift that keeps on giving. Following the darker edged Over the Fence as the second of two films released in 2016, Nobuhiro Yamashita’s My Uncle (ぼくのおじさん, Boku no Ojisan) pushes his subtle humour in a much more overt direction with a comic tale of a self obsessed (not quite) professor as seen seen through the eyes of his exasperated nephew. “Travels with my uncle” of a kind, Yamashita’s latest is a pleasantly old fashioned comedy spiced with oddly poignant moments as a wiser than his years nephew attempts to help his continually befuddled uncle navigate the difficulties of unexpected romance. Hitoshi One has a history of trying to find the humour in an old fashioned sleazy guy but the hero of his latest film, Scoop!, is an appropriately ‘80s throwback complete with loud shirt, leather jacket, and a mop of curly hair. Inspired by a 1985 TV movie written and directed by Masato Harada, Scoop! is equal parts satire, exposé and tragic character study as it attempts to capture the image of a photographer desperately trying to pretend he cares about nothing whilst caring too much about everything.

Hitoshi One has a history of trying to find the humour in an old fashioned sleazy guy but the hero of his latest film, Scoop!, is an appropriately ‘80s throwback complete with loud shirt, leather jacket, and a mop of curly hair. Inspired by a 1985 TV movie written and directed by Masato Harada, Scoop! is equal parts satire, exposé and tragic character study as it attempts to capture the image of a photographer desperately trying to pretend he cares about nothing whilst caring too much about everything.

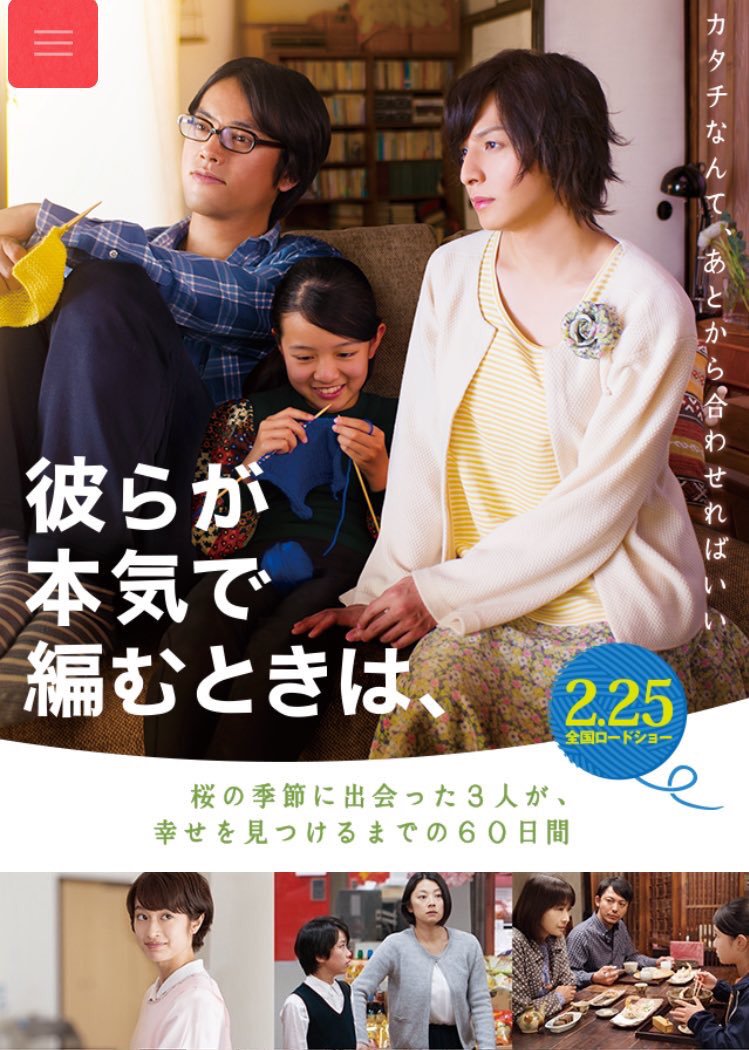

While studying in the US, director Naoko Ogigami encountered people from all walks of life but on her return to Japan was immediately struck by the invisibility of the LGBT community and particularly that of transgender people. Close-Knit (彼らが本気で編むときは, Karera ga Honki de Amu Toki wa) is her response to a still prevalent social conservatism which sometimes gives rise to fear, discrimination and prejudice. Moving away from the quirkier sides of her previous work, Ogigami nevertheless opts for a gentle, warm approach to this potentially heavy subject matter, preferring to focus on positivity rather than dwell on suffering.

While studying in the US, director Naoko Ogigami encountered people from all walks of life but on her return to Japan was immediately struck by the invisibility of the LGBT community and particularly that of transgender people. Close-Knit (彼らが本気で編むときは, Karera ga Honki de Amu Toki wa) is her response to a still prevalent social conservatism which sometimes gives rise to fear, discrimination and prejudice. Moving away from the quirkier sides of her previous work, Ogigami nevertheless opts for a gentle, warm approach to this potentially heavy subject matter, preferring to focus on positivity rather than dwell on suffering.

What is it that makes one person betray another? Following

What is it that makes one person betray another? Following