The ruins of a firebombed city become a purgatorial space haunted by tortured souls who cannot escape the traumatic wartime past in Shinya Tsukamoto’s eerie voyage through post-war Japan, Shadow of Fire (ほかげ, Hokage). Even the small boy (Ouga Tsukao) who desperately looks for a place to belong is plagued by nightmares of the flames that took his home and family while it otherwise seems that those around him live their lives in the shadow of a war which for many is still far from over.

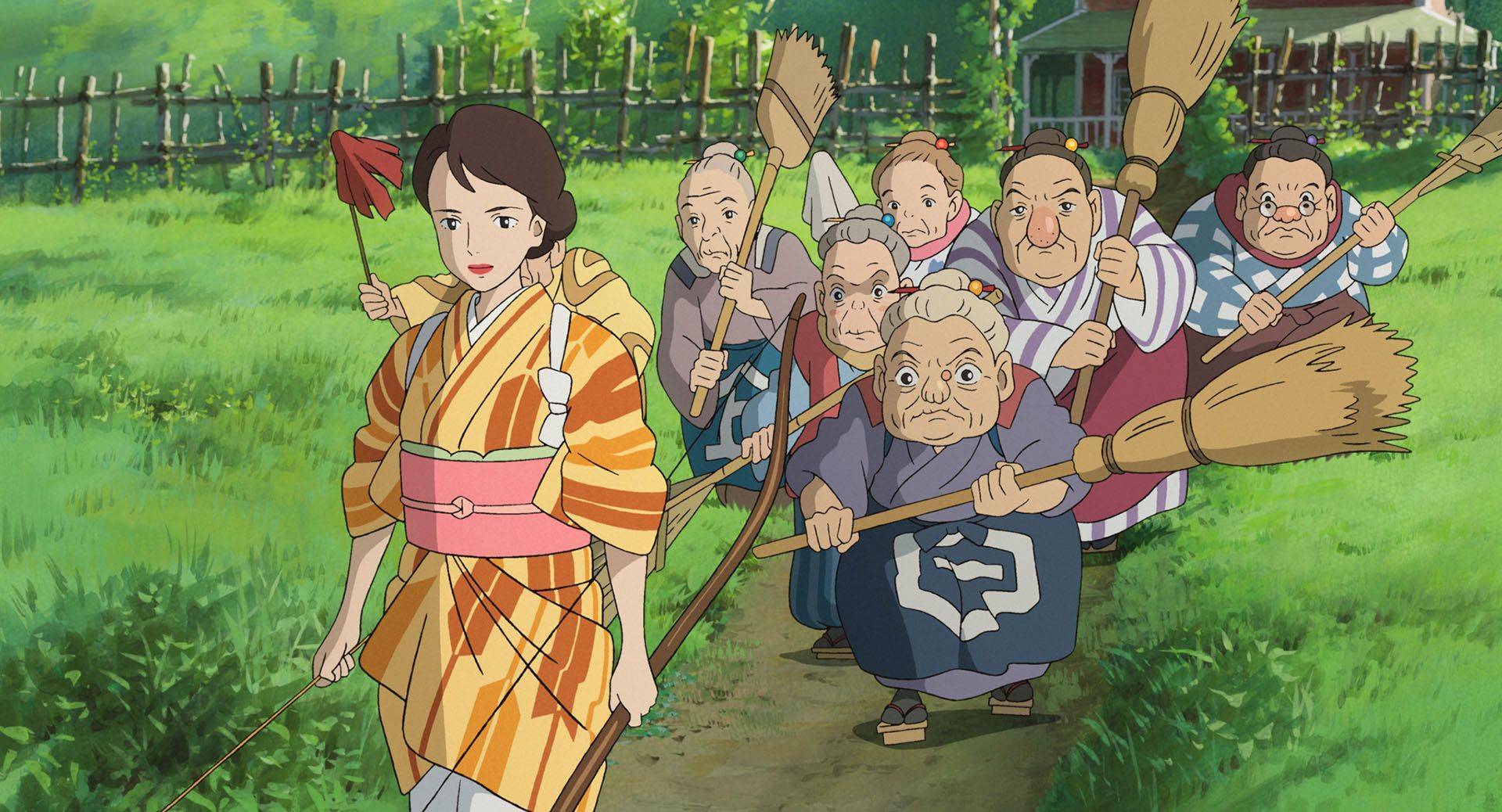

This state of ruination is immediately brought home to us by the heightened presence of sound. Not only do the cicadas buzz amid the scorching heat of an oppressive summer, but we constantly hear the sound of people walking over rubble or the clinking of broken glass. The unnamed woman we first meet (Shuri) lives in a room behind a small bar which appears to have scorch marks across the fusuma, a dank and dingy place filled with hopelessness and despair. The woman herself has a vacant look, a little dead behind the eyes either numbed with the sake a neighbourhood man brings her as pretext for extracting sexual favours or simply too tired of life to think much about it. Though she technically runs a bar, it’s more of a front for her only means of supporting herself, casual sex work, though as later becomes apparent she too may have been slow poisoned not only by the war but it’s immediate aftermath and the lingering traumas of those left behind and those who returned.

The boy who eventually comes to stay with her remarks that those who did not come back did not turn into scary people, as if they were somehow lucky to have escaped this purgatorial hellscape. Later he wanders through the black market and discovers an abandoned tunnel filled with returned soldiers who stare out at him with vacant eyes sitting with eerie stillness like dormant zombies. He spots a man among them that he knew well, a young soldier (Hiroki Kono) who had been a teacher before he was drafted and took a maths textbook with him to war as a kind of talisman that reminded him he’d survive and teach again. The soldier had formed an odd kind of family unit with the woman and the boy, almost as if the husband she lost in the war and son who died in the firebombing, had been returned to her but his trauma refuses to set him free surfacing in moments of unexpected violence that hint at war’s realities.

Later the boy meets another man with a traumatic past though one who sees himself as both victim and villain, resentful towards himself and the militarist regime that convinced him to betray his humanity and do dreadful, terrible things in its service. Tellingly this man, Shuji (Mirai Moriyama), is the only one granted a name. Perhaps names are only for the living, there’s a part of Shuji that is painfully alive a way that others aren’t even as he fixes his sights on his revenge as if it would somehow restore the humanity that was taken from him. Completing his quest, he lets down his hair and proclaims that for him at least the war is finally over. His commander, meanwhile, appears to have been living a fairly nice and successful life reminding him that he should stop dwelling on the past because it was after all a war and such things are only to be expected.

Shuji uses the boy in a way that seems counterproductive, taking advantage of the gun he’d found to help him take revenge on war. The woman tries to change the boy’s path, instructing him not to steal but to work honestly for his pay and to try to be better than this infinitely corrupted world. He wanted to be her protector, in his way acting as guide trying to free those around him from the purgatorial space of ruin and destitution but when he asks a medicine seller if he can exchange his money for something that will cure sickness he is told it’s not enough. He then tries to buy a dress for the woman, as if anticipating the salvation through consumerism that will eventually arrive though the constant sound of gunshots from the black market might indicate that for some at least there’s only one way out. The old man who visits the woman explains that he only approaches the ones who look okay, but that in the end you never really know. Shot in the half light or caught from behind the previously friendly take on an almost demonic intensity, wandering ghosts or broken souls already half consumed by the flames that in their minds at least are still burning and casting their shadows over the scorched earth of a traumatised society.

Shadow of Fire screened as part of this year’s Japan Foundation Touring Film Programme.

International trailer (English subtitles)