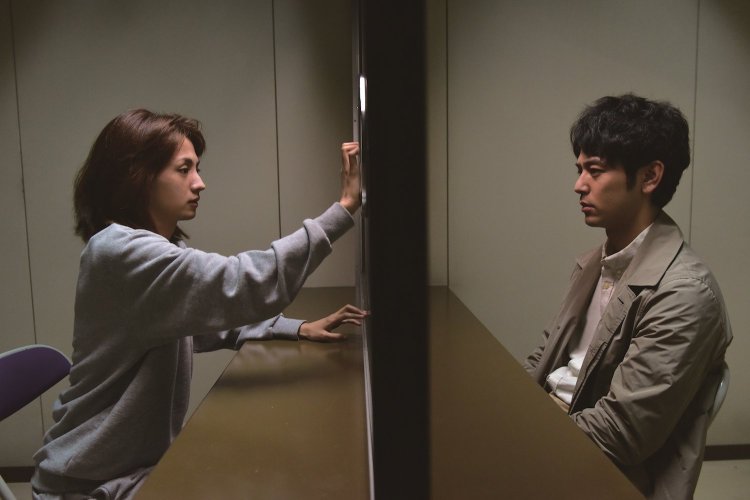

“Human beings are lonely by nature”, a statement offered by someone who could well think he’s lying but accidentally tells the truth in Kazuya Shiraishi’s Birds Without Names (彼女がその名を知らない鳥たち, Kanojo ga Sono Na wo Shiranai Toritachi). Loneliness, of an existential more than physical kind, eats away at the souls of those unable to connect with what it is they truly want until they eventually destroy themselves through explosive acts of irrepressible rage or, perhaps, of love. The bad look good and the good look bad but appearances can be deceptive, as can memory, and when it comes to the truths of emotional connection the sands are always shifting.

“Human beings are lonely by nature”, a statement offered by someone who could well think he’s lying but accidentally tells the truth in Kazuya Shiraishi’s Birds Without Names (彼女がその名を知らない鳥たち, Kanojo ga Sono Na wo Shiranai Toritachi). Loneliness, of an existential more than physical kind, eats away at the souls of those unable to connect with what it is they truly want until they eventually destroy themselves through explosive acts of irrepressible rage or, perhaps, of love. The bad look good and the good look bad but appearances can be deceptive, as can memory, and when it comes to the truths of emotional connection the sands are always shifting.

Towako (Yu Aoi), an unmarried woman in her 30s, does not work and spends most of her time angrily ringing up customer service departments to complain about things in the hope of getting some kind of compensation. She lives with an older man, Jinji (Sadao Abe) – a construction worker, who is completely devoted to her and provides both financial and emotional support despite Towako’s obvious contempt for him. Referring to him as a “slug”, Towako consistently rejects Jinji’s amorous advances and resents his, in her view, overly controlling behaviour in which he rings her several times a day and keeps general tabs on her whereabouts.

Depressed and on edge, Towako’s life takes a turn when she gets into a dispute with an upscale jewellery store over a watch repair and ends up beginning an affair with the handsome salesman who visits her apartment with a selection of possible replacements. Around the same time, Towako rings an ex-boyfriend’s number in a moment of weakness only to reconsider and hangup right away. The next day a policeman arrives and informs her that they’ve been monitoring her ex’s phone because his wife reported him missing five years ago and he’s not been seen since.

Towako views Jinji’s behaviour as possessive and his continuing devotion pathetic in his eagerness to debase himself for her benefit. Her sister Misuzu (Mukku Akazawa), however, thinks Jinji is good for her and berates Towako for her ill treatment of him. Despite the fact that Towako’s relationship with her ex, Kurosaki (Yutaka Takenouchi), ended eight years previously, Misuzu is paranoid Towako is still seeing him on the sly and will eventually try to get back together with him. Misuzu does not want this to happen because Kurosaki beat Towako so badly she landed in hospital, but despite this and worse, Towako cannot let the spectre of Kurosaki and the happiness promised in their earliest days go. She continues to pine for him, looking for other Kurosakis in the form of other handsome faces selling false promises and empty words.

Mizushima (Mukku Akazawa), the watch salesman, is just Towako’s type – something which Jinji seems to know when he violently pushes a Mizushima look-alike off a busy commuter train just because he saw the way Towako looked at him. Daring to kiss her when she abruptly starts crying while looking at his replacement watches, Mizushima spins her a line about an unhappy marriage and his craving for solitude which he sates through solo travel – most recently to a remote spot in the desert and cave they call an underground womb. Mizushima describes himself as a lonely soul and claims to have found a kindred spirit in Towako whose loneliness it was that first sparked his interest. Like all the men in the picture, Mizushima is not all he seems and there is reason to disbelieve much of what he says but he may well be correct in his assessment of Towako’s need for impossible connections with emotionally unavailable men who only ever cause her pain.

It just so happens that Kurosaki’s apparent disappearance happened around the time Towako began dating Jinji. Seeing as his behaviour is often controlling, paranoid and, as seen in the train incident, occasionally violent, Towako begins to suspect he may be involved in the mysterious absence of her one true love. Then again, Towako may well need protecting from herself and perhaps, as Misuzu seems to think, Jinji is just looking out for her. The deeper Jinji’s devotion descends, the more Towako’s contempt for him grows but the suspicion that he may be capable of something far darker provokes a series of strange and unexpected reactions in the already unsteady Towako.

A dark romance more than noirish mystery, Birds Without Names takes place in a gloomy Osaka soaked in disappointment and post-industrial grime where the region’s distinctive accent loses its sometimes soft, comedic edge for a relentless bite in which words reject the connection they ultimately seek. Rejection, humiliation, degradation, and a hopeless sense of incurable loneliness push already strained minds towards an abyss but there’s a strange kind of purity in the intensity of selfless love which, uncomfortably enough, offers salvation in a final act of destruction.

Screened as part of the Japan Foundation Touring Film Programme 2018.

Also screening at:

- Firstsite (Colchester) 9 February 2018

- HOME (Manchester) 12 February 2018

- Watershed (Bristol) – 13 February 2018

- Exeter Phoenix – 27 February 2018

- Depot (Lewes) – 6 March 2018

- Filmhouse (Edinburgh) – 8 March 2018

International trailer (English subtitles)

The

The  Yo Oizumi stars as a high school teacher investigating the disappearance of a friend in another darkly comic, twist filled farce from Kenji Uchida (

Yo Oizumi stars as a high school teacher investigating the disappearance of a friend in another darkly comic, twist filled farce from Kenji Uchida ( Kazuya Shiraishi (

Kazuya Shiraishi ( When a schoolgirl falls off a roof foul play is suspected. Who better to investigate than her fellow members of the literature club at an elite academy catering to the daughters of the rich and famous?

When a schoolgirl falls off a roof foul play is suspected. Who better to investigate than her fellow members of the literature club at an elite academy catering to the daughters of the rich and famous? A young reporter (Satoshi Tsumabuki) investigates the brutal murder of a model family whilst trying to support his younger sister (Hikari Mitsushima) who is currently in prison for child neglect while his nephew remains in critical condition in hospital. Interviewing friends and acquaintances of the deceased, disturbing truths emerge concerning the systemic evils of social inequality.

A young reporter (Satoshi Tsumabuki) investigates the brutal murder of a model family whilst trying to support his younger sister (Hikari Mitsushima) who is currently in prison for child neglect while his nephew remains in critical condition in hospital. Interviewing friends and acquaintances of the deceased, disturbing truths emerge concerning the systemic evils of social inequality.  Based on a best selling romantic novel which captured the hearts of readers across Japan, Initiation Love sets out to expose the dark and disturbing underbelly of real life romance by completely reversing everything you’ve just seen in a gigantic twist five minutes before the film ends…

Based on a best selling romantic novel which captured the hearts of readers across Japan, Initiation Love sets out to expose the dark and disturbing underbelly of real life romance by completely reversing everything you’ve just seen in a gigantic twist five minutes before the film ends… A young woman goes missing and unwittingly becomes the face of a social movement in Daigo Matsui’s anarchic examination of a misogynistic society.

A young woman goes missing and unwittingly becomes the face of a social movement in Daigo Matsui’s anarchic examination of a misogynistic society. A brother and sister are orphaned after a natural disaster and taken in by relatives but struggle to come to terms with the aftermath of such great loss.

A brother and sister are orphaned after a natural disaster and taken in by relatives but struggle to come to terms with the aftermath of such great loss. Miwa Nishikawa adapts her own novel in which a self-centred novelist is forced to face his own delusions when his wife is killed in a freak bus accident.

Miwa Nishikawa adapts her own novel in which a self-centred novelist is forced to face his own delusions when his wife is killed in a freak bus accident.  When the statute of limitations passes on a series of unsolved murders, a mysterious man (Tatsuya Fujiwara) suddenly comes forward and confesses while the detective (Hideaki Ito) who is still haunted by his inability to catch the killer has his doubts in Yu Irie’s adaptation of Jung Byoung-Gil’s Korean crime thriller Confession of Murder.

When the statute of limitations passes on a series of unsolved murders, a mysterious man (Tatsuya Fujiwara) suddenly comes forward and confesses while the detective (Hideaki Ito) who is still haunted by his inability to catch the killer has his doubts in Yu Irie’s adaptation of Jung Byoung-Gil’s Korean crime thriller Confession of Murder. Toma Ikuta stars as maverick cop Reiji in Takashi Miike’s madcap manga adaptation. Reiji has been kicked off the force for trying to arrest a councillor who was molesting a teenage girl but gets secretly rehired to go undercover in Japan’s best known yakuza conglomerate.

Toma Ikuta stars as maverick cop Reiji in Takashi Miike’s madcap manga adaptation. Reiji has been kicked off the force for trying to arrest a councillor who was molesting a teenage girl but gets secretly rehired to go undercover in Japan’s best known yakuza conglomerate. Yoshihiro Nakamura (

Yoshihiro Nakamura ( Yuzo Kawashima would have turned 100 in 2018. A comic tale of life on the Osakan margins, Room For Let is a perfect example of the director’s well known talent for satire and stars popular comedian Frankie Sakai as an eccentric writer/translator-cum-konnyaku-maker whose life is turned upside down when a pretty young potter moves into the building.

Yuzo Kawashima would have turned 100 in 2018. A comic tale of life on the Osakan margins, Room For Let is a perfect example of the director’s well known talent for satire and stars popular comedian Frankie Sakai as an eccentric writer/translator-cum-konnyaku-maker whose life is turned upside down when a pretty young potter moves into the building. Embittered 55 year old OL Setsuko gets a new lease on life when introduced to an unusual English conversation teacher, John, who gives her a blonde wig and rechristens her Lucy. “Lucy” falls head over heels for the American stranger and decides to follow him all the way to the states…

Embittered 55 year old OL Setsuko gets a new lease on life when introduced to an unusual English conversation teacher, John, who gives her a blonde wig and rechristens her Lucy. “Lucy” falls head over heels for the American stranger and decides to follow him all the way to the states…  A remake of Korean hit

A remake of Korean hit  A small boy recruits the mysterious samurai “No Name” as a bodyguard after his dog is injured in an ambush in the landmark animation from 2007.

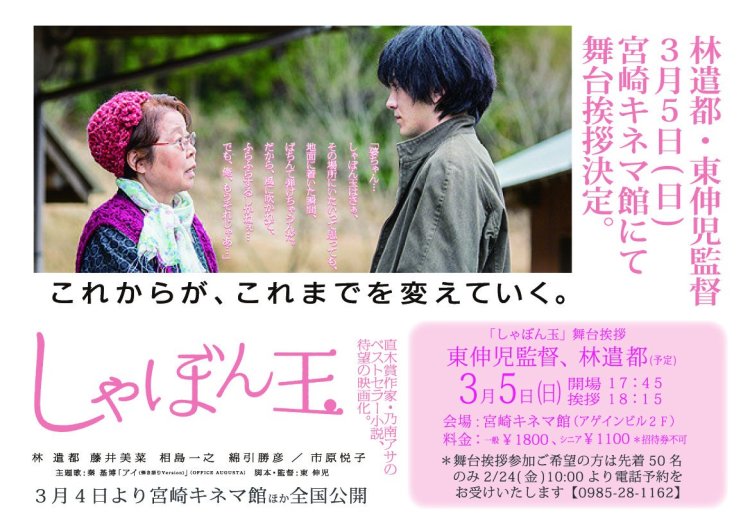

A small boy recruits the mysterious samurai “No Name” as a bodyguard after his dog is injured in an ambush in the landmark animation from 2007. A no good lowlife makes his way by stealing from elderly women but experiences a change of heart when he’s taken in by a kindly old lady deep in the mountains.

A no good lowlife makes his way by stealing from elderly women but experiences a change of heart when he’s taken in by a kindly old lady deep in the mountains.

Generally speaking, murder mysteries progress along a clearly defined path at the end of which stands the killer. The path to reach him is his motive, a rational explanation for an irrational act. Yet, looking deeper there’s usually something else going on. It’s easy to blame society, or politics, or the economy but all of these things can be mitigating factors when it comes to considering the motives for a crime. Gukoroku – Traces of Sin (愚行録), the debut feature from Kei Ishikawa and an adaptation of a novel by Tokuro Nukui, shows us a world defined by unfairness and injustice, in which there are no good people, only the embittered, the jealous, and the hopelessly broken. Less about the murder of a family than the murder of the family, Gukoroku’s social prognosis is a bleak one which leaves little room for hope in an increasingly unfair society.

Generally speaking, murder mysteries progress along a clearly defined path at the end of which stands the killer. The path to reach him is his motive, a rational explanation for an irrational act. Yet, looking deeper there’s usually something else going on. It’s easy to blame society, or politics, or the economy but all of these things can be mitigating factors when it comes to considering the motives for a crime. Gukoroku – Traces of Sin (愚行録), the debut feature from Kei Ishikawa and an adaptation of a novel by Tokuro Nukui, shows us a world defined by unfairness and injustice, in which there are no good people, only the embittered, the jealous, and the hopelessly broken. Less about the murder of a family than the murder of the family, Gukoroku’s social prognosis is a bleak one which leaves little room for hope in an increasingly unfair society.

Self disgust is self obsession as the old adage goes. It certainly seems to ring true for the “hero” of Miwa Nishikawa’s latest feature, The Long Excuse (永い言い訳, Nagai Iiwake) , in which she adapts her own Naoki Prize nominated novel. In part inspired by the devastating earthquake which struck Japan in March 2011, The Long Excuse is a tale of grief deferred but also one of redemption and self recognition as this same refusal to grieve forces a self-centred novelist to remember that other people also exist in the world and have their own lives, emotions, and broken futures to dwell on.

Self disgust is self obsession as the old adage goes. It certainly seems to ring true for the “hero” of Miwa Nishikawa’s latest feature, The Long Excuse (永い言い訳, Nagai Iiwake) , in which she adapts her own Naoki Prize nominated novel. In part inspired by the devastating earthquake which struck Japan in March 2011, The Long Excuse is a tale of grief deferred but also one of redemption and self recognition as this same refusal to grieve forces a self-centred novelist to remember that other people also exist in the world and have their own lives, emotions, and broken futures to dwell on.