When you think of the family drama, you think of a young woman getting married and that her marriage is an unambiguously good and righteous thing despite the pain it may bring to her parents who will obviously miss her yet must comfort themselves that they’ve done everything right. In melodrama, however, we get quite a different picture of the “modern” marriage in which it is not quite so unambiguously good or righteous but a patriarchal trap enabled by a kind of gaslighting which tells women that suffering is the natural condition of life and that they should wear their unhappiness as a badge of honour.

Nowhere does this seem truer than in the films of Yuzo Kawashima who in general takes quite a dim view of romance as a path to freedom and finds his heroines struggling to escape outdated social codes to seize their own freedom. Hungry Soul (飢える魂, Ueru Tamashii) finds one still comparatively young woman and another middle-aged discovering that they want more out of life than their society thinks a woman is supposed to have but continuing to wrestle with themselves over whether or not they have the right to pursue their personal happiness in a rigidly conservative society.

Reiko (Yoko Minamida), a woman in her early 30s, married Shiba (Isamu Kosugi), 23 years her senior, 10 years previously apparently out of a mix of youthful naivety and post-war desperation. Shiba has supported her financially and apparently enabled her brother’s career, but it’s clear that he thinks of her as little more than a glorified housemaid, treating her with utter contempt even in public. He makes her carry her own bags at the station rather than wait for a porter and forces her to accompany him on business trips where he shows her off to colleagues and then retires her to the hotel with nothing to do all day. Tyrannised, Reiko has been been raised to be obedient and does her best to be a good wife, but Shiba repeatedly reminds her that he bought her while openly talking about his relationships with other women even at one point bringing a geisha home with him while Reiko cringes in the front seat next to the driver.

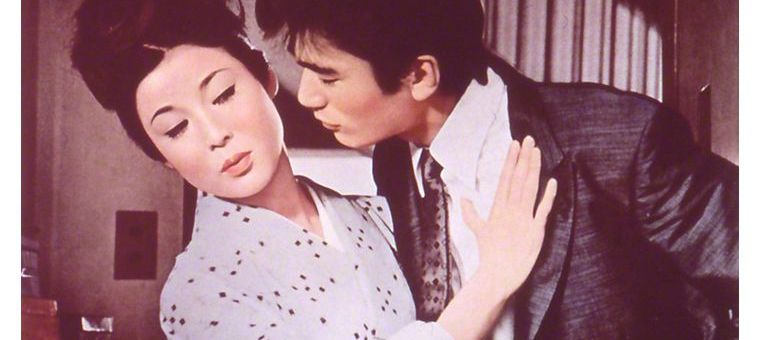

Perhaps what she’s learning is that obedience is not an unambiguously good quality, but still she struggles to let go of the necessity of measuring up to the standards of social propriety. When Shiba unwittingly introduces her to handsome politician Tachibana (Tatsuya Mihashi), her accidental attraction to him awakens her to all the ways her married life is a hell of disappointment. Shiba reminds her that he keeps her in comfort, little understanding that she may hunger for something more than the material, while Reiko realises that she may starve to death for lack of love but has been conditioned to think that a woman’s emotional needs are not only unimportant but entirely taboo.

Mayumi (Yukiko Todoroki), meanwhile, has known love but feels obliged to live on the memory of her late husband and fulfil herself only though caring for her two teenage children. To do that, paradoxically, she has seized her independence as a working woman with a job in real estate, later hoping to manage a ryokan traditional style hotel, only for her children to resent her perceived rejection of motherhood in favour of individual fulfilment. “School is for people who have two parents” her son tells her, threatening to move out into a dorm, while her daughter at one point considers suicide simply because she suspects her mother may be sleeping with her late father’s best friend.

In Reiko’s case, her desire for liberation is kickstarted by a hunger for love, though as we later realise Tachibana is also perhaps looking to break with the past and with conventional male behaviour in that he has been a womanising playboy involved in relationships with women from the red light district which to him were always casual while they, like Reiko and Mayumi, longed for more. Mayumi’s relationship with Shimozuma (Shiro Osaka), by contrast, is complicated by the fact he is married to a woman with a long-term illness, though what he craves (besides Mayumi herself for whom he seems to have been carrying a torch for many years) is a conventional family home, jokingly chiding Mayumi that her interest in business may be making her less “womanly”.

Both women try, and fail, to break free of patriarchal control to claim their own agency, discovering that romance is not the best way to find freedom. Despite her love for and possibly misplaced faith in Tachibana, Reiko is both too brutalised by her abusive husband and constrained by the taboo of being a woman ending a marriage for another man to definitively escape Shiba’s control. Mayumi, meanwhile, is shamed by the reflection of herself in her children’s eyes and motivated to reassume her maternity but does so also as a way of rejecting easy romantic fulfilment in the hope of discovering more of herself as a middle-aged woman embracing all the freedom that might offer while her children, though grateful to have her return to them, are also chastened and guilty in having realised that their mother is a woman too and ultimately they just want her to be happy. As often in Kawashima, no one quite gets what they wanted, but they do at least find a kind of resolution. Their souls may still be hungry, but their appetites have returned and there is the promise of future fulfilment if still tempered by the restrictions of a cruelly repressive society.

Hungry Soul opening (no subtitles)

Hungry Soul, Part II opening (no subtitles)

By 1962 the Japanese economy had begun to improve and with the Olympics on the horizon the nation was beginning to look forward towards hoped for prosperity rather than back towards the intense suffering that had defined the post-war era. There would be, however, a kind of reckoning to be had if not quite yet. Yuzo Kawashima’s Elegant Beast (しとやかな獣, Shitoyakana Kemono) is perhaps among the first to start asking questions about what the legacy of the immediate aftermath of the war might be. It may have been impossible to survive with one’s integrity entirely intact, but how should one proceed now that there is less need to be so self serving, calculating, and cruel when there is more food on the table?

By 1962 the Japanese economy had begun to improve and with the Olympics on the horizon the nation was beginning to look forward towards hoped for prosperity rather than back towards the intense suffering that had defined the post-war era. There would be, however, a kind of reckoning to be had if not quite yet. Yuzo Kawashima’s Elegant Beast (しとやかな獣, Shitoyakana Kemono) is perhaps among the first to start asking questions about what the legacy of the immediate aftermath of the war might be. It may have been impossible to survive with one’s integrity entirely intact, but how should one proceed now that there is less need to be so self serving, calculating, and cruel when there is more food on the table?