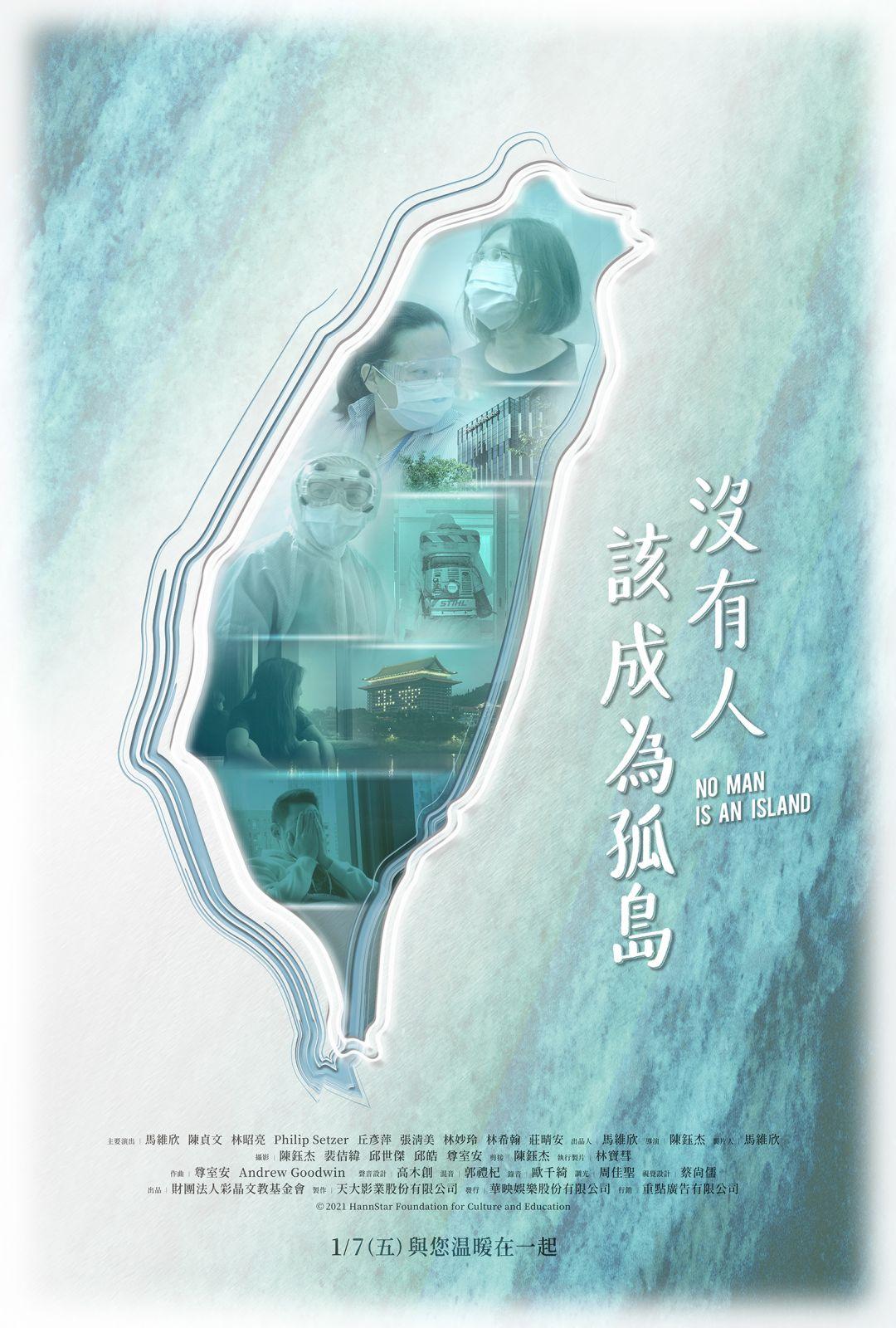

For much of the pandemic, Taiwan was regarded as a success story having largely managed to avoid mass infections through a well formulated public health programme that meant for many life could carry on more or less as normal. Jay Chern’s documentary No Man is an Island (沒有人該成為孤島, méi yǒurén gāi chéngwéi gūdǎo) focusses on the sometimes forgotten frontline workers that made that sense of normality possible while losing their own in situating itself in a small hotel which agreed to become a quarantine facility for travellers arriving from overseas.

Chern spends much of his time with the hotel’s manager, Rebecca Ma, who at one point describes the decision to house those needing to quarantine as the biggest mistake of her life but also something she ultimately felt was the right thing to do, that it would be wrong to refuse when they had the capability to help. Nevertheless, she makes clear that her greatest responsibility was to her staff, negotiating with the government that they’d only agree to offer quarantine services if they’d be provided with full PPE while we can also see the extensive procedures they must take to keep the the guests and themselves safe disinfecting rooms after guests leave and allowing several hours before deep cleaning them while running UV disinfectant lamps throughout the building.

Meanwhile, they also face some pushback from the local community upset by the close proximity to those who may be carrying COVID-19 only to be reminded that if they weren’t quarantining at the hotel they’d have to go somewhere else and could even be staying in the apartment below theirs so the point is in many ways moot. Even within the hotel Ma is well aware of how boring and distressing being trapped in quarantine could be even in a hotel as nice as hers fully preparing herself for a series of picky complaints from guests with quite literally nothing else to do taking out their frustrations on the front desk team. Meanwhile, others forget that it’s not a holiday, they’re in quarantine, and want access to normal hotel services around the clock not always taking kindly to being reminded that certain things may not be possible.

With that in mind, it’s genuinely touching to see the level of care that the hotel staff have for those staying with them taking note of their mental health as well as the physical. Ma recounts personally preparing a meal for the first few quarantiners and is often seen organising special treats for the guests particularly in the holiday periods so that they don’t feel alone as if the hotel staff is their family even gifting pretty flowers and cupcakes for mother’s day as well as small toys to keep children entertained. She herself has been living away from her family in the hotel to keep everything running smoothly while further members of staff move in later during the stricter lockdowns put in place after the situation intensifies ironically because of lax quarantine processes at another hotel which allowed airline personnel to leave earlier than otherwise recommended.

Mindful of her responsibilities, Ma makes a point of leading by example never asking anyone else to do something she wouldn’t or put themselves in harm’s way unnecessarily. One employee reflects that she was so frightened that she wrote her will and explained to friends what to do with her ashes should the worst happen, but in general the atmosphere among the staff seems cheerful and upbeat, Ma giggling that she feels like a naughty child ringing people’s doorbells and then running away to let them know their meals have arrived. Privately she admits that the situation can be stressful because no mistakes can be made, it is quite literally a matter of life and death, but also a job she just needs to keep doing to the best of her ability.

Chern also speaks to a few of the quarantiners one of whom is his own mother returning from the US to care for his bedridden grandmother, while others have returned to be closer to their families or because it is simply safer in Taiwan than wherever they were before, allowing each of them to chronicle their experiences in their quarantine diary as they try to stave off cabin fever and the anxieties of their long journeys home. Hanns House has become for them a small safe haven until they’re able to go back out into the world. “Sometimes life isn’t about what we want or if you’re ready, but rather if it’s necessary” Ma adds, later reflecting that the pandemic is turning into a never-ending marathon, “If you can’t run, crawl to the very end”.

No Man is an Island streams in the US April 4 – 10 as part of the 14th season of Asian Pop-Up Cinema.

Original trailer (English subtitles)