The jitsuroku yakuza movie which had become dominant in the mid-70s had often told of the rise and fall of the petty street gangster from the chaos of the immediate post-war era to the economically comfortable present day. The jitsuroku films didn’t attempt to glamourise organised crime and often presented their heroes as men born of their times who had been changed by their wartime experiences and were ultimately unable to adjust themselves to life in the new post-war society. Adapted from a serialised novel by Akimitsu Takagi which ran from 1959 to 1960, Toru Murakawa’s Dead Angle (白昼の死角, Hakuchu no Shikaku) by contrast speaks directly to the contemporary era in following a narcissistic conman who has no need to live a life of crime but as he says does evil things for evil reasons.

Prior to the film’s opening in 1949, the hero Tsuruoka (Isao Natsuyagi) had been a law student at a prestigious Tokyo university where he nevertheless became involved in the Sun Club, a student financial organisation launched by mastermind Sumida (Shin Kishida) who eventually commits suicide by self-immolation when the organisation collapses after being accused of black market trading. An unrepentant Tsuruoka resolves to start again, rebuilding in the ashes as a means of kicking back against hypocritical social institutions and rising corporate power by utilising his legal knowledge to run a series of cons through the use of promissory notes to prove that the law is not justice but power.

In this Tsuruoka has an ironic point. He doesn’t pretend what he’s doing is legal, only that he’s safeguarded himself against prosecution. When a pair of yakuza thugs break into his office and threaten him in retaliation for a con he ran on a shipping company, he reminds them that as they’ve had him open the safe it would make the charge of killing him robbery plus murder which means automatic life imprisonment rather than the few years they might get for simply killing him without taking any money. He always has some reason why the law can’t touch him, while implicitly placing the blame on his victims who were often too greedy or desperate to read the small print and therefore deserve whatever’s coming to them. In at least one case, Tsuruoka’s victimless crimes end up resulting in death with one old man whom he’d double conned, pretending to give him the money he was owed but getting him drunk and talking him into “re-investing” the money with him, takes his own life by seppuku in the depths of his shame not only in the humiliation of having been swindled but losing his company, who had trusted him, so much money.

You could never call Tsuruoka’s rebellion an anti-capitalist act, but it is perhaps this sense of corporate tribalism symbolised by the old man’s extremely feudalistic gesture that Tsuruoka is targeting. As his wife Takako (Mitsuko Oka) tells him, Tsuruoka should have no problem making an honest living. After all he graduated in law from a top university, it’s not as if he wouldn’t have been financially comfortable and it doesn’t seem that the money is his primary motive. While Takako continues to insist that he’s a good person who wouldn’t do anything “illegal”, his longterm geisha mistress Ayaka (Yoko Shimada) knows that he’s an evil man who does evil things for evil’s sake and that’s what she likes about him. Elderly businessmen are always harping on about the “irresponsible youth” of the day but all are too quick to fall for Tsuruoka’s patter while he is essentially nothing more than a narcissist who gets off on a sense of superiority laughing at the law, the police, and the corporate landscape while constantly outsmarting them.

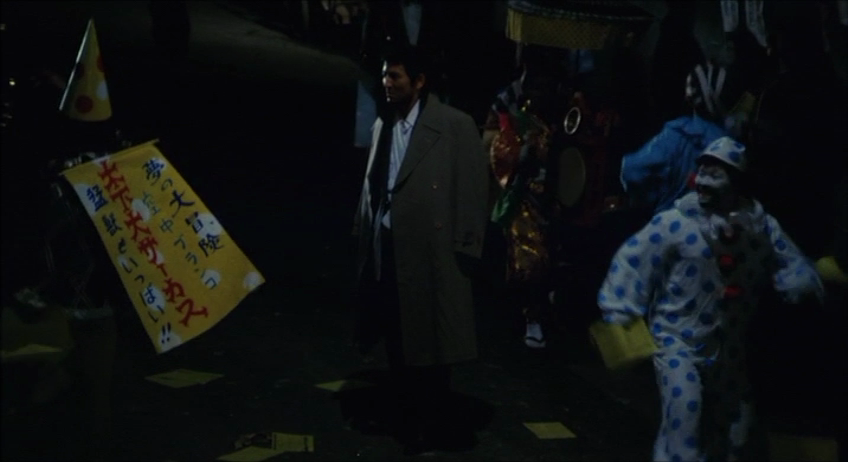

In this, the film seems to be talking to the untapped capitalism of the 1970s. Like Tsuruoka, the nation now has no need to get its hands dirty and should know when enough is enough but is in danger of losing sight of conventional morality in the relentless consumerist dash of the economic miracle. That might explain why unlike the jitsuroku gangster pictures, Murakawa scores the film mainly with an anachronistic contemporary soundtrack along with the ironic use of saloon music in the bar where Tsuruoka’s associates hook an early target, and the circus tunes which envelope him at the film’s opening and closing hinting that this is all in some ways a farce even as Tsuruoka is haunted by the ghosts his narcissistic greed has birthed. Then again perhaps he too is merely a product of his times, cynical, mistrustful of authority, and seeking independence from a hypocritical social order but discovering only failure and exile in his unfeeling hubris.

Original trailer (no subtitles)