“Fate brings people together, no matter how far” according to a wise old chef in early ‘90s New York. He’s not wrong though Peter Chan’s seminal 1996 tale of fated romance Comrades, Almost a Love Story (甜蜜蜜) is in its own way also about partings, about the failure of dreams and the importance of timing in the way time seems to have of spinning on itself in a great shell game of interpersonal connection. But then, it seems to say, you get there in the end even if there wasn’t quite where you thought you were going.

As the film opens, simple village boy from Northern China Xiaojun (Leon Lai Ming) arrives in Hong Kong in search of a more comfortable life intending to bring his hometown girlfriend Xiaoting (Kristy Yeung Kung-Yu) to join him once he establishes himself. His first impressions of the city are not however all that positive. In a letter home, he describes the local Cantonese speakers as loud and rude, and while there are lots of people and cars there are lots of pickpockets too. It’s in venturing into a McDonald’s, that beacon of capitalist success, that he first meets Qiao (Maggie Cheung Man-Yuk), a cynical young woman hellbent on getting rich who nevertheless decides to help him by whispering in Mandarin realising he doesn’t understand the menu. Hailing from Guangdong, Qiao can speak fluent Cantonese along with some English and thus has much better prospects of succeeding in Hong Kong but takes Xiaojun under wing mostly out of loneliness though accepting a kickback to get him into an English language school where she piggybacks on lessons while working as a cleaner. Bonding through the music of Teresa Teng, they become friends, and then lovers, but Xiaojun still has his hometown girlfriend and Qiao still wants to get rich.

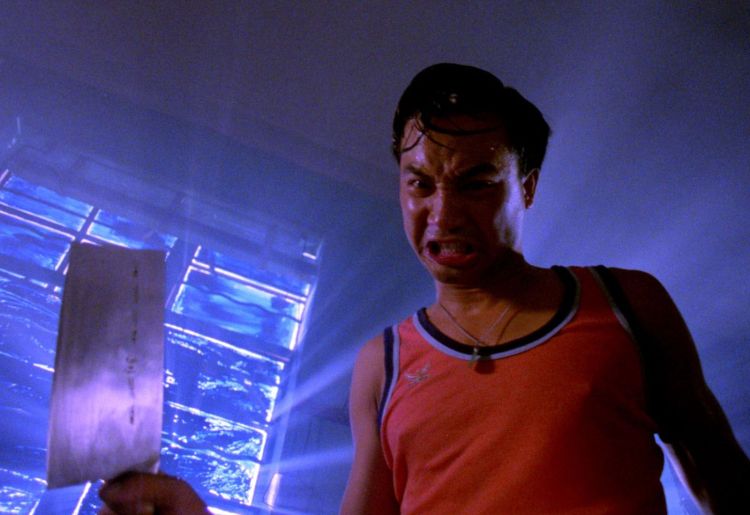

As we later learn in one of the film’s many coincidences, Xiaojun and Qiao arrived on the same train if facing in different directions. Hong Kong changes each of them. When Xiaojun eventually manages to bring Xiaoting across the border, he’s no longer the simple village boy he was when he arrived while Qiao struggles with herself in her buried feelings for Xiaojun unwilling to risk the vulnerability of affection but visibly pained when confronted by Xiaojun’s responsibility to Xiaoting. She finds her mirror in tattooed gangster Pao (Eric Tsang Chi-Wai) who, like her, shrinks from love and is forever telling her to find another guy but is obviously hoping she won’t as afraid of settling as she is.

For each of them this rootlessness is born of searching for something better yet the irony is as Xiaojun says that Hong Kong is a dream for Mainlanders, but the Mainland is not a dream for most in Hong Kong who with the Handover looming are mainly looking to leave for the Anglophone West. Qiao’s early business venture selling knock off Teresa Teng tapes fails because only Mainlanders like Teresa Teng so no-one wants to buy one and accidentally out themselves in a city often hostile to Mandarin speakers as Xiaojun has found it to be. What they chased was a taste of capitalist comforts, Qiao literally working in a McDonald’s and forever dressed in Mickey Mouse clothing which Pao ironically imitates by getting a little Mickey tattooed on his back right next to the dragon’s mouth. But when they eventually end up in the capitalist homeland of New York, a driver chows down on a greasy, disgustingly floppy hamburger while Qiao finds herself giving tours of the Statue of Liberty to Mainland tourists in town to buy Gucchi bags who tell her she made a mistake to leave for there are plenty of opportunities to make money in the new China.

Ironically enough it’s hometown innocence that brings them back together. The ring of Xiaojun’s bicycle bell catches Qiao’s attention though she’d thought of it as a corny and bumpkinish when he’d given her rides on it in their early days in Hong Kong. Xiaojun had in fact disposed of it entirely when Xiaoting arrived partly for the same reason and partly because it reminded him of Qiao. The pair are reunited by the death of Teresa Teng which in its own way is the death of a dream and of an era but also a symbol of their shared connection, Mainlanders meeting again in this strange place neither China nor Hong Kong, comrades, almost lovers now perhaps finally in the right place at the right time to start again. Peter Chan’s aching romance my suggest that the future exists in this third space, rejecting the rampant consumerist desire which defined Qiao’s life along with the wholesome naivety of Xiaojun’s country boy innocence, but finally finds solid ground in the mutual solidarity of lonely migrants finding each other again in another new place in search of another new future.

Comrades, Almost a Love Story screens at Soho Hotel, London on 9th July as part of Focus Hong Kong’s Making Waves – Navigators of Hong Kong Cinema.

Short clip (English subtitles)

Teresa Teng – Tian Mi Mi