“Grave Robber” is ordinarily not a nice thing to call someone, let alone to be, yet the heroes of Park Jung-bae’s Collectors (도굴, Do-gul) are just that if in effect more like cultural Robin Hoods robbing the dead to reclaim the past than heartless thieves interested only in profit. Operating with a “this should be in a museum!” mentality, these grave robbers have a variety of motives, among them revenge both personal and national, as they take aim at lingering historical betrayals stemming back to the days of Japanese colonialism.

As the film opens, intrepid thief Dong-gu (Lee Je-hoon) manages to trick a pair of Buddhist monks suspicious on the grounds that he’s a bit handsome for the religious life into letting him “guard” a pagoda that’s set for imminent dismantling in order to nab a precious miniature Buddha located inside. What puzzles the authorities is that Dong-gu leaves obvious evidence of the theft along with a trademark chocopie wrapper which suggests he wants everyone to know how clever he is. This may be true, Dong-gu is quite smug about his obvious abilities as a tomb raider, but he may also have ulterior motives in play. As a duplicitous broker points, out, however, it’s surprisingly difficult to make money trafficking artefacts because they are simply to famous to be sold openly meaning thieves and fences are all dependent on a small pool of super rich “collectors” with whom they have personal relationships or else are stealing to order.

Stepping back a little, what this means is that not only are those like Dong-gu robbing the dead and selling their affects on the black market, but that they are in a sense traitors to their nation often selling these precious historical artefacts to foreigners and most problematically to the Japanese, ironically enough grave robbers themselves in having looted half the country during the colonial era. It will come as little surprise that the main villain Jin Sang-gil (Song Young-chang), a hotel entrepreneur and head of the Korea Cultural Asset Foundation, in fact owes his inherited wealth to his family having sold artefacts to the Japanese from 1910 onwards, and himself is keeping a large selection of plundered treasures in an ultra secure vault underneath his offices.

The Buddha brings Dong-gu into Jin’s orbit, first made an offer by his gangster underling Gwang-chul (Lee Sung-wook) who is, perhaps conveniently, Chinese-Korean hailing from Yanbian, and then by his smart assistant Sae-hee (Shin Hye-sun) who is fluent in English, Chinese, and Japanese acting as a broker for wealthy Japanese clients which is how she finances Dong-gu’s upcoming operation to steal an ancient frieze from a grave located in what is now technically China but was then Korean. Dong-gu, meanwhile, despite claiming he got into grave robbing because he realised he’d never be able to buy a house working “like regular people do”, is remarkably uninterested in the money refusing Sae-hee’s “gift” of a fancy car, and instantly losing his fee in the hotel casino. As we later realise, what he seems to want is for the artefacts to be returned to their rightful owners, the Korean people.

To complete his heist he recruits a series of “experts” including the slightly nerdy souvenir peddler nicknamed “Dr. Jones” (Jo Woo-jin) who even dresses like Indy himself, as well as a former miner recently released from prison renowned for his tunnelling abilities. Dong-gu’s methods are traditional in the extreme, locating the entrance to a burial mound by tasting the soil looking for traces of decomposing flesh, while his sister Hye-ri (Park Se-wan) is much more technologically advanced making frequent use of drones and angering her father and brother by drilling a tiny hole in the Buddha to insert a GPS tracker hoping to figure out what Jin is doing with the artefacts. In a touch of irony, the vault has itself been designed to mimic the security features of an ancient tomb if updated with biometric eye scanning and fingerprint technology topped off with a good old-fashioned key, but as it turns out there’s no security system that can protect you from betrayal especially if you’re generally unpleasant and no one trusts you anyway.

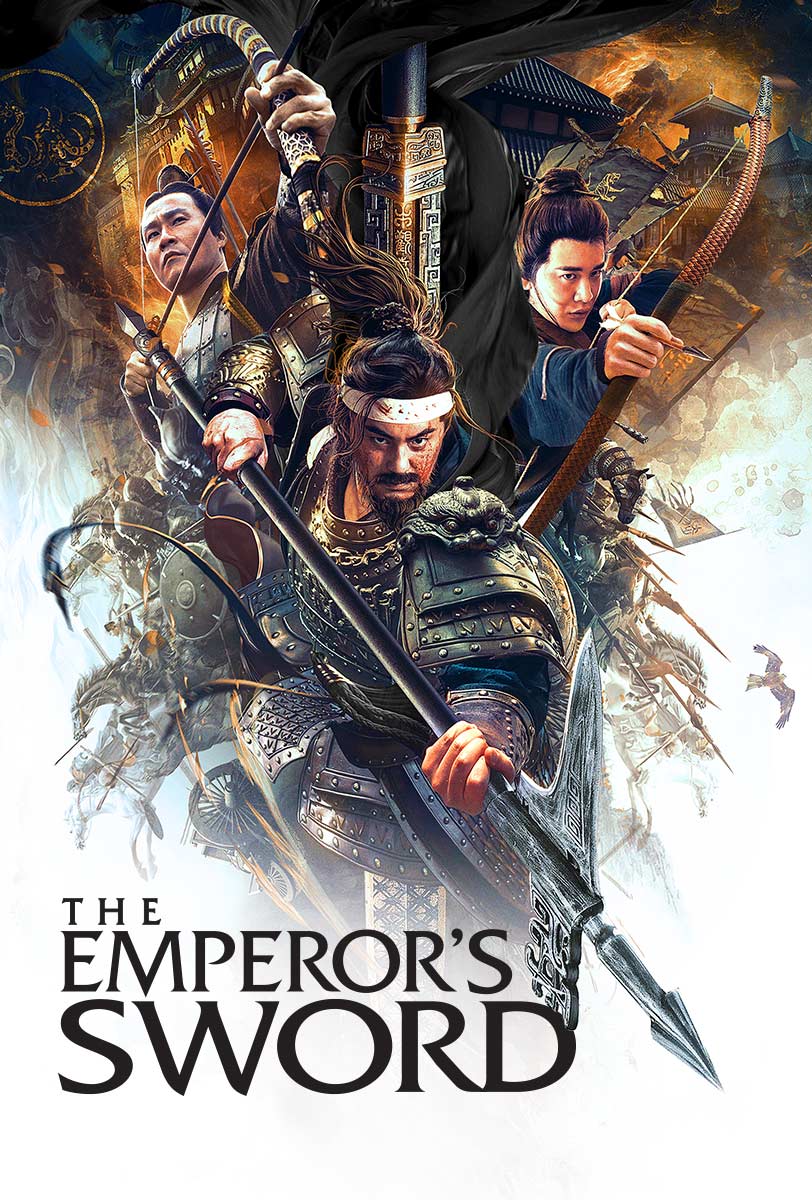

Dong-gu’s target, however, is a royal tomb located in the centre of Gangnam from which he intends to steal the “Excalibur of Joseon” appealing to Jin’s sense of hubris, leaning into a kind of mythical prophecy in which he’d become a contemporary hero ruling over all Korea as the wielder of the sword. Taking in some additional social commentary in which the government has chosen to improve their approval ratings through spending money buffing up a tomb while when the guys try to rent a subbasement the flirtatious realtor admits the rents are low in this area because it often floods only to shake off some of her disapproval when they tell her they’re part of the restoration team, the central message is that the historical relics of Korea’s past belong to the Korean people, not to the shady businessmen further corrupting an already compromised economy, nor to former colonial powers. Sometimes, it seems to say, digging up the past is a necessary act of national reclamation.

Collectors screens 13th November as part of this year’s London Korean Film Festival.

International trailer (English subtitles)