An ambitious young woman determined to escape the world of sex work resorts to a series of schemes to get close to the number one beauty in 1930s Saigon in Vũ Ngọc Đãng’s lighthearted melodrama Sister Sister 2 (Chị Chị Em Em 2). A thematic sequel to 2019’s Sister Sister, the film once again sees two women face off against each other knowing that only one can be the greatest beauty in the city while otherwise evoking a subtle message of female empowerment.

Indeed as great beauty Ba Tra (Minh Hằng) points out, ordinary women can only be chosen by men while the extraordinary choose men for themselves. This is something in which Ba Tra has excelled, weaponising her beauty and sex appeal to capture the hearts of well to do bachelors who spontaneously offer her expensive gifts for which she need do nothing in return save continue to exist. Nhi (Ngọc Trinh), the top sex worker at a nearby brothel, wonders if Ba Tra is so different from herself only to be told by a gaggle of local women in thrall to her star image that Ba Tra’s situation is entirely different because of the power she wields over men by, essentially, refusing to give them what they want while Nhi crudely exchanges it for money and is largely at the mercy of those who will pay.

The issue is in one sense control, Ba Tra seemingly possessing it fully and Nhi not at all. She is still indentured to the brothel having sold herself into sex work to pay for her mother’s medical treatment only for her mother to drop dead of shock as soon as she found out. But Ba Tra also has maternal troubles of her own in her “crazy gambler” mother who is forever emotionally blackmailing her for more money while caring nothing for her feelings. To be the first beauty is to make friends with loneliness, Ba Tra warns and there is a kind of sadness in her solitude as a towering image of beauty not quite allowed to be a whole person or display much of an interior life lest the spell be broken. There is then something quite poignant in the genuine connection that arises between the two sisters who after all have similar goals and outlooks even if it’s destined to end in heartbreak when Ba Tra inevitably realises she’s been schemed by the manipulative Nhi.

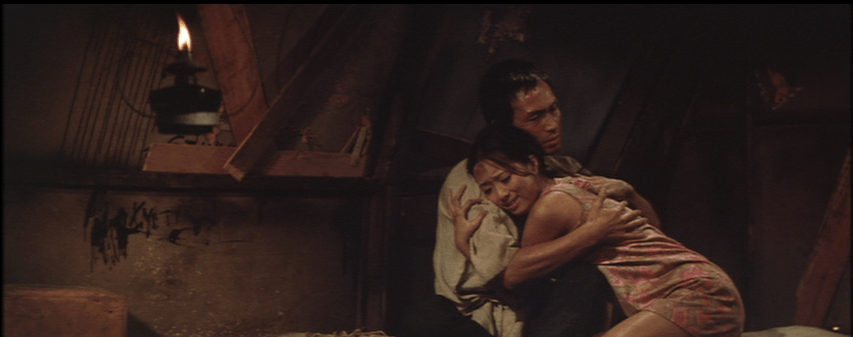

Director Vũ Ngọc Đãng flirts with homoeroticism in the closeness of the two women as they dance together perfecting their art but does so mainly for titillation rather than romance, also resorting to family gratuitous nudity even if it does otherwise hint at Nhi’s “naked” ambition to raise herself from the lowest layer of the society to the highest or at least the highest that may be claimed by a woman in this period. The film at once hints at the oppressive nature of the 1930s society in which the only power a woman can achieve is that exercised through her body and then undercuts any sense of a feminist message with its contradictory conclusion that implies it is impossible for Nhi to escape her past and that she will always be a sex worker no matter what else she becomes.

Nevertheless, Nhi does demonstrate her right to the top spot through her ability to outsmart Ba Tra who otherwise has savvily figured out how to use the society to her advantage through careful media management to make herself a star. As she says, Ba Tra only thinks about the next move, but Nhi has already plotted her trajectory towards the top and thought of every eventuality. Even so, Nhi is expected to pay for her “mad ambition”, putting her back in her place again and slapping down her rebellion against the social order. With mild comic undertones in all Nhi’s crazy plans which include faking her own death and almost killing Ba Tra so she can dramatically save her, Sister Sister 2 isn’t really setting out to explore the lives of women in the 1930s so much as set two against each other in a battle of the beauties but is surprisingly entertaining even in its wilful silliness.

Trailer (English subtitles)