Phenomenally popular Cantopop boyband Mirror have been dominating the Hong Kong box office lately with several of the guys playing regular roles in movies not particularly designed as vehicles for their star persona such as Anson Lo’s turn in arty horror It Remains, or Lokman Yeung in Mad Fate. We 12 (12怪盜) is however the first time the band have made a movie altogether as an ensemble star vehicle and is clearly intended for their many devoted fans filled as it is with what seem to be in jokes and references to the guys’ “real” personas or at least those of the “character” they play in terms of their membership of Mirror.

The guys’ solo projects and movie work are perhaps hinted at in the film’s central thesis, if you can call it that, in that the boys have been doing too many solo missions and have lost their team spirit. In the universe of the film, they’re a kind of crime fighting zodiac who do things like save princesses and conduct jewel heists. Each of the band members, who use similar character names, is introduced with a special power which ranges from the ability to converse telepathically with animals to the nebulous “strategic planning” and the downright plain “abseiling” which seems particularly unfair given that any of the other guys could obviously learn to abseil too and then he wouldn’t have a power anymore.

In any case, their group mission is to stop a mad scientist from activating a device which can send mosquitos to other universes because it would destroy our ecosystem. Meanwhile other scientists are working on creating a “right-wing chicken” which turns out to be less political than it sounds and in fact much more absurd, along with a series of other cancer causing foods just in case you weren’t sure if they were really “evil” or not. Even so, the plot isn’t really important more a means of tying the silliness together given that focus is split between the 12 guys who each have their particular moment to shine and personalised gags. When the big job goes wrong because they decided to all do their own thing rather than work as a team, they have to come back together again and rediscover the equilibrium of Kaito (i.e. Mirror).

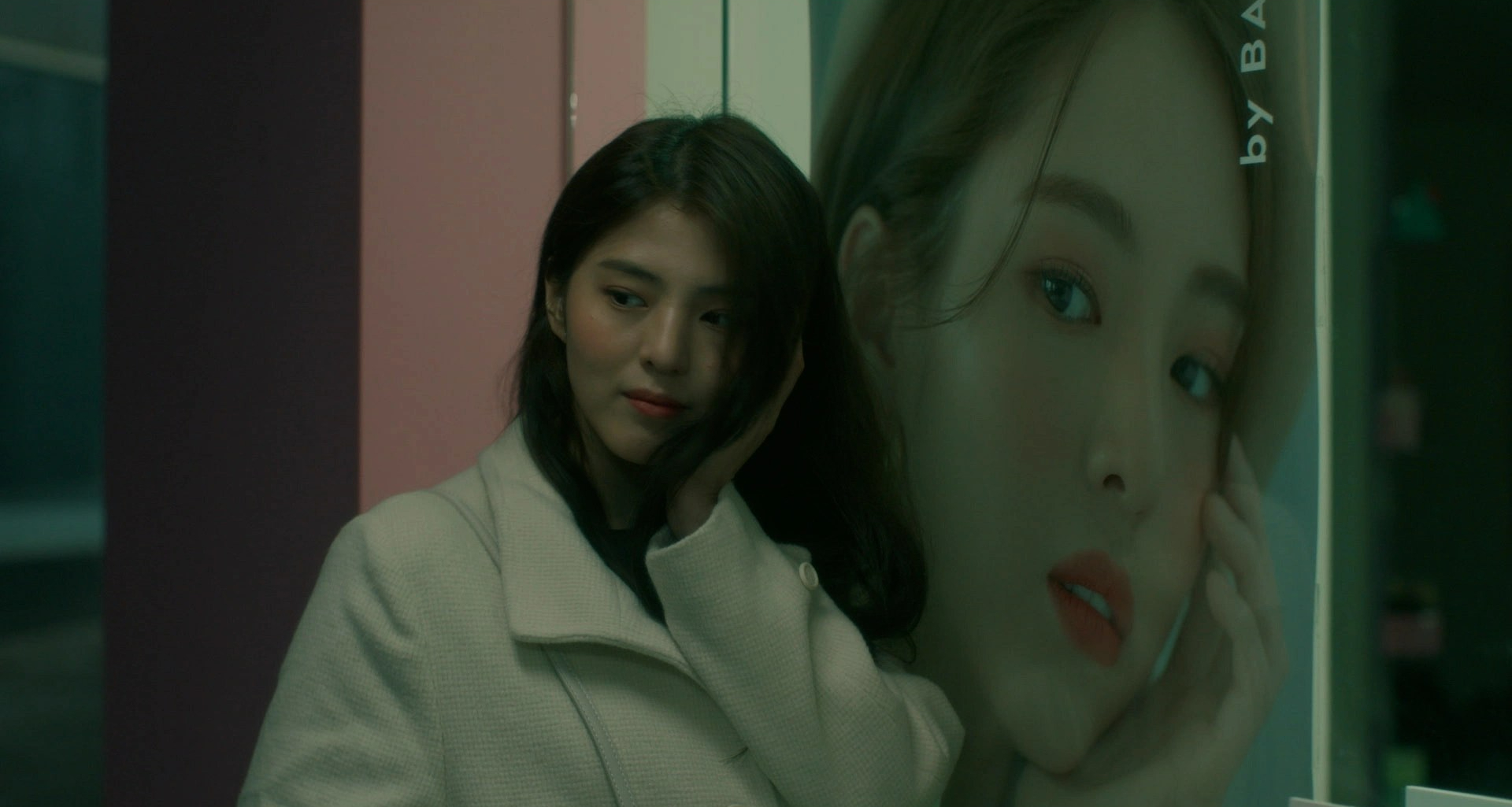

Which is all to say, it’s a little impenetrable to the uninitiated but fans of the band will doubtless be in heaven. It’s all in the grand tradition of boyband popstar movies in which the silliness is sort of the point in generating a sense of conspiracy with fans that they’re the ones who get the jokes because of their intimate relationships with the stars. The film also features extended cameos from fellow Cantopop group Error who play their back up team and have a few gags of their own, while Malaysian actress and star of Table for Six Lin Min Chen also has a small cameo as the kidnapped princess.

The best performance comes however from The Sparring Partner’s Yeung Wai-lun as the slimy security manager Johnny who is obsessed with order and dresses in fascist uniform so obviously out of keeping with the silliness and absurdity the boys represent in a mild kind of rebellion towards anything serious or grown up society in general. There is something quite childish about the way the gags suddenly pop up out of nowhere along with the otherwise nonsensical nature of the film which isn’t so much a nonsense comedy like those of the 80s and 90s as much something totally random perhaps intended to express the essence of Mirror or at least that which its fans believe it to be. For all of these reasons, the film makes very little literal sense and does not hang together very well for anyone not already well versed in the world of the band but presumably plays out just fine for anyone with a 21st-century equivalent of a decoder ring and a silly sense of humour willing to join the boys for whatever crazy adventure they may be embarking on next.

WE 12 is on UK cinemas now courtesy of CineAsia.