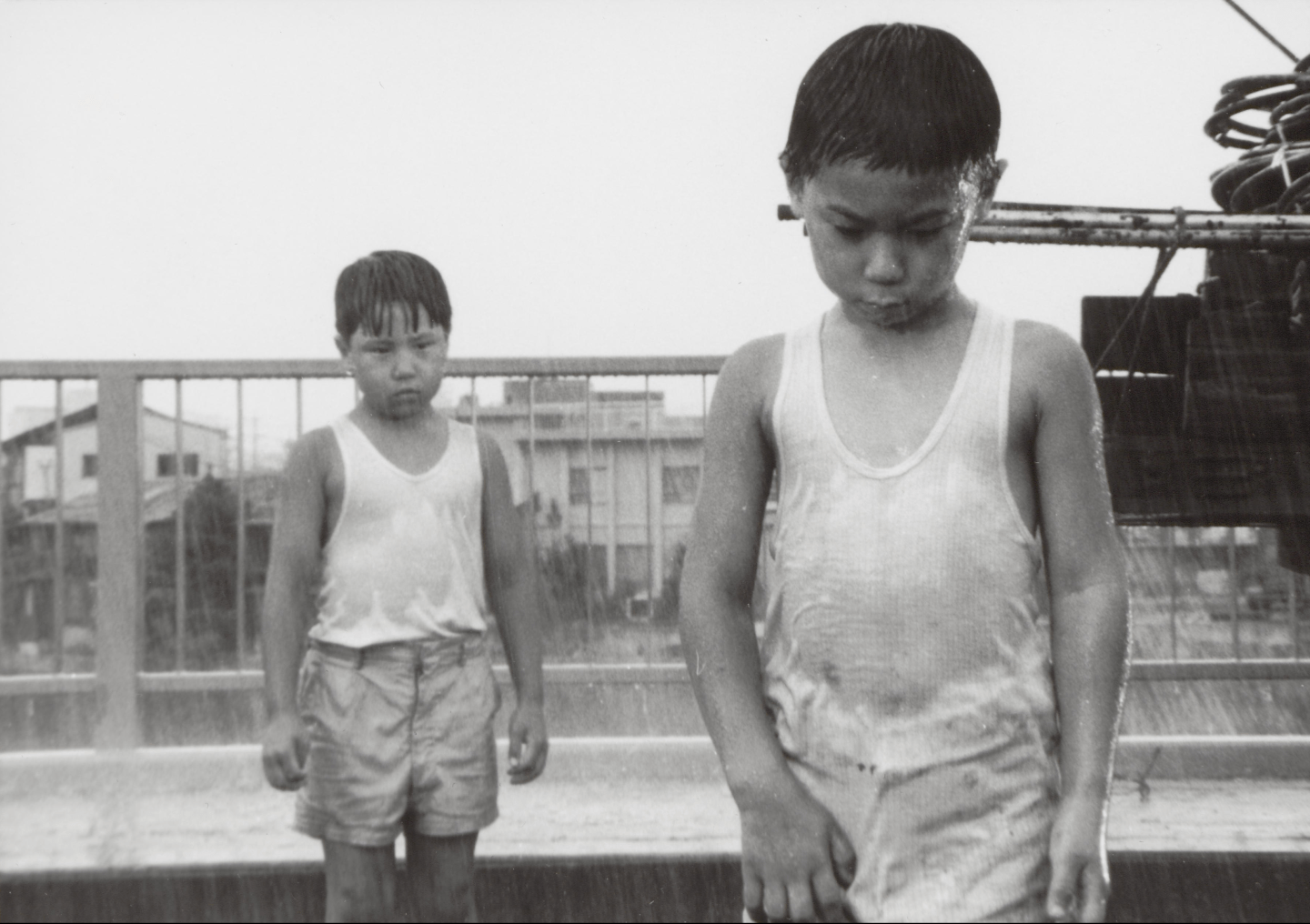

Sometimes home is the hardest place to go. At least that’s how it is for the eponymous Yoko (658km、陽子の旅, 658km, Yoko no Tabi) in Kazuyoshi Kumakiri’s emotional road movie in which a defeated middle-aged woman is jolted out of her self-imposed inertia on hearing of the sudden death of the father she had not seen in over 20 years. As much about a moment of mid-life reevaluation as one woman’s gradual return to the world through a process of self-acceptance, the film displays a boundless empathy not to mention a sense of warmth out of keeping with a snowbound winter in northern Japan.

At 42, Yoko (Rinko Kikuchi) lives alone in a one room apartment that she seemingly never leaves. Ironically enough, she works as a customer service assistant operating a remote chat box in which she encourages the customer to try turning it off and on again but otherwise offers little real support. When she accidentally breaks her phone, he first thought is to try contacting the online consumer helpline only to realise the irony of her situation and think better of it. In a moment of cosmic coincidence she receives a visit from her cousin, Shigeru (Pistol Takehara), who explains that her sister Rie has been trying to call but obviously couldn’t get through because of the broken phone. Yoko’s father has passed away suddenly. Shigeru and his family are making the long drive from Tokyo to Aomori and they’ve been instructed to bring Yoko with them for the funeral the day after next.

We can tell that Yoko is no longer used to interacting with other people. Her voice is almost inaudible and her words tumble out in a half-confused jumble. Shigeru seems sympathetic and we can interpret that she’s been this way a long time, if not all of her life. He asks her if she has clothes for the funeral and is unsurprised when she gives no answer, assuring her they can sort it out when they get there while trying to cajole her downstairs and into the car where his wife and kids are waiting. The kids are, predictably, incredibly noisy and a little insensitive while the mother tries to get some sleep and Shigeru sings a folksong that was a favourite of her father’s. His spectre (Joe Odagiri), not so much a ghost as a manifestation of her memory silently, haunts her throughout the journey reminding of her of her unresolved shame and the reasons she had avoided contact with him for the last 20 years.

These moments are full of painful melancholy but also an underlying sense of dread as if Yoko were being stalked by her own self-loathing projected onto the figure of father. After becoming separated from Shigeru at a service station and assuming she’s been abandoned with no phone and only loose change, she decides to hitchhike to Aomori and in effect travels backward meeting echoes of herself as she goes. Her first driver is a woman of about her own age (Asuka Kurosawa) in Tokyo for a job interview who reflects her buried cynicism, remarking that she resents the people she sees at service stations who to her at least seem far too happy. On learning that Yoko has no children and never married, she chuckles that she couldn’t imagine a life without out them hinting at another life Yoko might have led and perhaps quietly yearns for in her solitude.

Yoko answers the woman with only grunts and a shake of the head, unable to communicate and in effect too shy to ask for help from passing strangers. Through her journey she gradually recovers the ability to speak, her words eventually pouring out of her in a voluntary monologue to a stranger on whose kindness she has become dependent. But in a girl she meets at the next rest stop she sees only her teenage self, the girl answering that it’s too hard to explain when questioned about why she’s hitchhiking alone in the middle of the night. When she gives her her scarf, it’s like a gift from her younger self, a small moment of embrace and support. Something similar happens as she approaches the area affected by the 2011 tsunami and meets a kindly older couple who represent her parents as she might have wished them to be rather than as they were. While the man gives her some fatherly advice, not unkindly, the woman (Jun Fubuki) gives her a pair of sheepskin boots in another gift of warmth that further proves to her that the world is full of kindness even if not all of the people who gave her rides were nice.

There maybe something in the fact that Yoko has to travel through the disaster zone in order to emerge from it, journeying towards the site of her trauma and beginning to overcome it as she comes to accept her father’s death and that is simply too late for many things though crucially not for all. What she comes to realise is, as her first driver told her, everyone has their reasons and she wasn’t the only one carrying a heavy burden. She only made it as far as she did because of the kindness of strangers and those, like Shigeru, who are willing to wait for her to come in from the cold. Rinko Kikuchi’s extraordinarily nuanced performance along with the snowbound vistas and melancholy score conjure a poignant atmosphere but one oddly buoyed with warmth in which the world can be a kind place or least as long as we can be kind to ourselves.

Yoko screens Feb. 22 as part of Family Portrait: Japanese Family in Flux

Original trailer (no subtitles)